Woolly mammoths last roamed the Earth some 4,000 years ago, but their tusks—fashioned into sculptures, jewelry, and trinkets—have become hot commodities in China, where elephant ivory is now banned.

Chinese craftsmen have carved both kinds of ivory for thousands of years, but mammoth ivory, taken from long-frozen carcasses that occasionally emerged from Siberia, has been cheaper and considered of poorer quality. With the legal elephant ivory market shuttered, however, Russian hunters are combing the tundra in search of mammoth tusks for buyers in Hong Kong and mainland China, where wholesale prices are about $450 per pound, comparable to elephant ivory prior to the ban.

Mammoth ivory “has proved to be a very useful substitute and they’ve got huge stocks of it now in China,” said Lucy Vigne, a wildlife consultant and investigator into ivory and rhino horn trading. “They’re quite happy to sell that now in place of elephant ivory.”

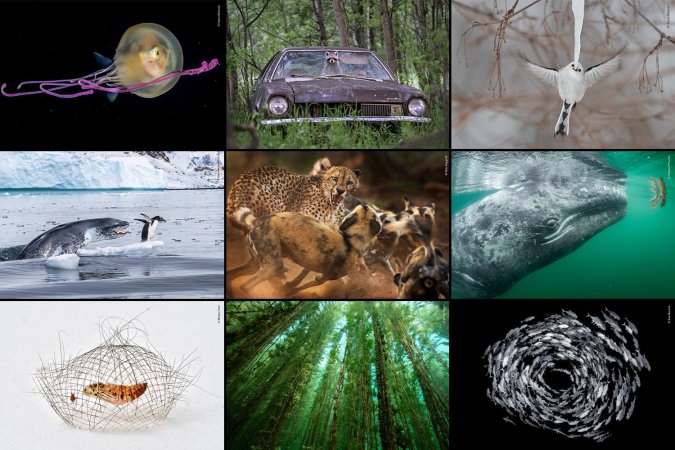

The problem is that elephant and mammoth tusks are so similar when carved into trinkets and jewelry that they can easily be mixed up. There is already evidence that elephant ivory is being illegally sold as mammoth ivory, and some experts fear laundering might become even more serious in the future. But rather than seek an outright ban, some conservationists and policymakers are pushing to regulate the trade of mammoth tusks as though they were products from a living endangered species—a radical move that would afford an extinct animal the same regulatory protections as lions, polar bears, and whale sharks.

A proposal put forth by Israel at this month’s meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in Geneva, Switzerland, would have allowed the trade of mammoth tusks to remain legal, but required member countries to issue permits for all exports and imports, and record those transactions in an international database. And countries would have had to enact serious measures to ensure that ivory exported or imported as mammoth isn’t actually elephant in disguise.

The proposal was discussed by representatives from the member nations but ultimately withdrawn— though officials agreed to authorize a study.

“We know there is a trade in mammoth ivory [and] we know that some is being intentionally mislabeled as elephant ivory,” said Simon Nemtzov, a wildlife ecologist at the Israel Nature and Parks Authority and Israel’s Scientific Authority for CITES. The extent of the problem, however, he said, is unknown.

“Our proposal might sound strange,” Nemtzov added, “to list an extinct species in a convention whose purpose is to protect endangered species, but the whole goal was to prevent laundering of elephant ivory and to cut down on poaching and illegal trafficking.”

During the past decade, demand for ivory in China and other Asian countries triggered a surge in elephant poaching in Africa. From 2007 to 2014, savanna elephant populations declined by 30 percent, while forest elephant numbers fell by 62 percent from 2002 to 2011. Acknowledging China’s role in the crisis, President Xi Jinping in 2017 banned virtually all domestic ivory sales.

Mammoth ivory, however, remains legal to buy and sell in China and almost everywhere else except India, and the trade is almost completely unregulated. In addition, unlike the international trade in elephant ivory, which has been banned since 1989, no overarching rules govern the export and import of mammoth ivory between countries.

Woolly mammoth carcasses and bones are found at many sites around the world, but to be suitable for carving their tusks must have been preserved in permafrost—otherwise they crumble when carved, said Adrian Lister, a paleobiologist at the Natural History Museum in London. Millions of such remains are frozen in Siberia and, to a lesser extent, in Canada and Alaska.

Until recently, mammoth tusks were only traded in small quantities. “There was one main Russian dealer who amassed it from collectors in Siberia,” then mostly sold it on to Hong Kong, Vigne said, adding: “He was always very free with his information.”

Now, however, many more hunters and dealers seem to be involved. “The trade is out of control,” Vigne said.

Mammoth ivory has been steadily gaining popularity since the early 2000s, but the Chinese ban caused many craftsmen and sellers to adopt it as a primary substitute. Ivory hunters in Russia quickly caught on and now search Siberia’s wilderness each summer, blasting into the tundra with high-pressure water jets. “They’re not doing any favors to the tundra, a fragile ecosystem of the far north,” Lister said.

No one knows how many groups or individual hunters are involved, but their numbers seem to be rising. And climate change is making their work easier by thawing out the ground more deeply and for longer stretches. As a result, “more mammoth carcasses have been found probably in the past 20 years than in the previous 200,” Lister said.

According to Vigne’s research, the vast majority of Siberia’s mammoth ivory winds up in mainland China or Hong Kong. Hong Kong upped its imports from 24 tons in 2009 to more than 59 tons 2014, and Vigne found that it’s only increased from there. In a 2018 investigation of markets in Guangzhou, she noted that the number of mammoth ivory items for sale “has soared,” she said.

Full mammoth tusks—which have a brown exterior and tend to be large and curved—can be easily distinguished from straighter, whiter and smaller elephant tusks. But once carved into more diminutive items, they can be difficult to distinguish, and thus an attractive laundering device for criminals.

Evidence already exists that illegal elephant ivory is being intentionally mislabeled as legal mammoth ivory. Vigne documented the problem in China in 2011 and 2014. And in 2017, a New York-based antiques dealer received a felony conviction for selling elephant ivory mislabeled as “carved mammoth tusks.”

Some experts believe mammoth ivory should be banned altogether. “As long as mammoth ivory is helping to keep ivory trade going, there will always be demand for modern [elephant] ivory as well,” Lister said.

Banning such a product under CITES, however, requires clear scientific evidence that its trade is threatening a species’ survival. In the case of mammoth tusks and their potential impact on elephants, a direct link has yet to be established. In addition, CITES representatives take more than science into account when determining how to vote on a new listing. Commercial interests from carvers and sellers, for one thing, are also considered.

In addition, conservationists, economists, and behavioral scientists are divided over whether it is more effective to focus on reducing demand for banned wildlife products like elephant ivory, or to flood the market with look-alike products, as a way to satisfy consumers and undercut illegal markets. “It’s not purely scientific issues that affect whether elephant ivory or other things are traded,” Nemtzov said.

Indeed, most experts, including Nemtzov, believe mammoth ivory should not be banned but regulated to ensure it doesn’t serve as a smokescreen for elephant ivory.

Nemtzov and his colleagues from Israel—often a leader in elephant conservation issues—tried to introduce regulations for mammoth ivory at the previous CITES conference in 2016, but were met with pushback from a number of officials who were concerned about “the added burden of bureaucracy, of having to check things, and of not being 100 percent sure if the trade is really an issue,” Nemtzov said.

At the latest conference, they tried to sway their colleagues by putting together a formal proposal complete with evidence of laundering of elephant ivory. The attempt to list products from an extinct species in CITES is very unusual and likely a first, says Susan Lieberman, vice president of international policy at the Wildlife Conservation Society. “No one is going to trade saber tooth cat teeth and have someone think they’re tiger,” she said. But because carved mammoth ivory looks so much like elephant ivory, it’s only logical to keep regulatory tabs on it.

The proposal, she said, was a “valid effort to say, ‘There’s a problem here. We don’t know how big the problem is, so let’s regulate it.’” But getting the international community on board, she added, was never going to be “a slam dunk.”

In a reply to Israel’s early request for comments, for example, Heidi Führmann, a member of the European Union’s CITES team, wrote that the treaty should be focused on conserving living species, “not on species that are long extinct.”

Discussing the proposal this week at the conference in Geneva, a U.S. representative added that regulating mammoth trade through CITES would cause increased regulatory hassle and divert resources from combatting elephant ivory smuggling. While Vigne believes more studies are needed on mammoth ivory trade, she thinks monitoring should be the responsibility of Russia and China, not the entire international community. (Both nations opposed Israel’s proposal on grounds that CITES does not apply to extinct species.)

“My view is that we need to focus on the big problems together—on trying to resolve what’s going on with poached ivory leaving Africa and stuff coming out of China,’’ Vigne said. “No one’s laundering African elephant ivory coming out of Africa as mammoth ivory.”

Even though the proposal did not pass this time, Lieberman hopes it at least highlighted the need to be vigilant. “If someone says it’s mammoth, don’t assume it is—take a look,” she said. “I don’t know if that will happen, but I give Israel credit for at least raising the issue.”

Rachel Love Nuwer is a freelance science journalist whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic, Scientific American, BBC Future, and elsewhere. She is the author of “Poached: Inside the Dark World of Wildlife Trafficking.”

This article was originally published on Undark with support from the Pulitzer Center. Read the original article.