North Atlantic right whales are among the world’s most endangered animals. Hunted for hundreds of years and well into the 20th century, there are roughly 400 swimming the western North Atlantic today, according to a 2012 report by the NOAA Fisheries Service. In the eastern North Atlantic there are so few that the population is effectively extinct.

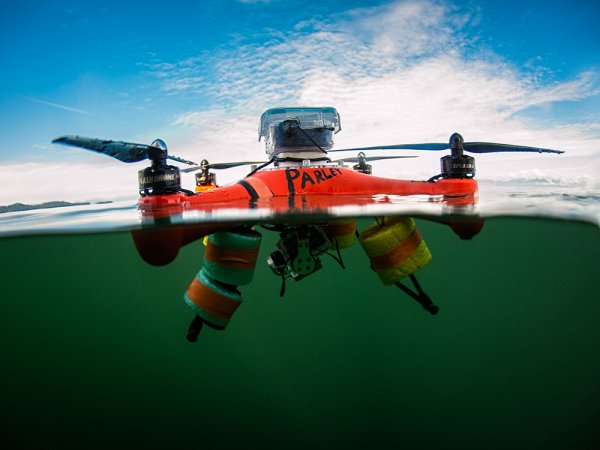

These days, the threats to northern right whales include getting tangled up in fishing gear, which can injure and kill them. But there may be a simple solution: Change the color of the ropes.

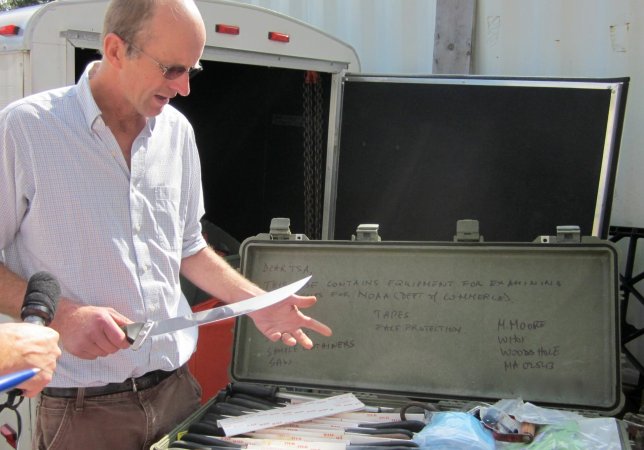

According to a recent article by the Associated Press, researcher Scott Kraus of the New England Aquarium told a fishing industry conference last week that whales react more strongly to certain colors. He and colleagues learned which by suspending PVC pipe lengths colored orange, red, green, and black underwater, near right whales feeding in Cape Cod Bay off the Massachusetts coast. The pipes stood in for what whales would normally encounter: ropes connecting underwater traps to floating buoys.

Kraus told the Maine Fishermen’s Forum that the whales reacted more often to red or orange pipes, and bumped into these pipes less often, than to those colored green or black, the AP reported.

Color arises based on which wavelengths of light a substance absorbs, and which it reflects or emits. Whale eyes are adapted to low undersea light, and see the world in black and white, but distinguish between different wavelengths of light underwater in order to find prey, as the AP article notes:

Kraus is reportedly working with manufacturers to create experimental red ropes, which Maine lobstermen will field test for utility and durability in comparison to typical ropes.

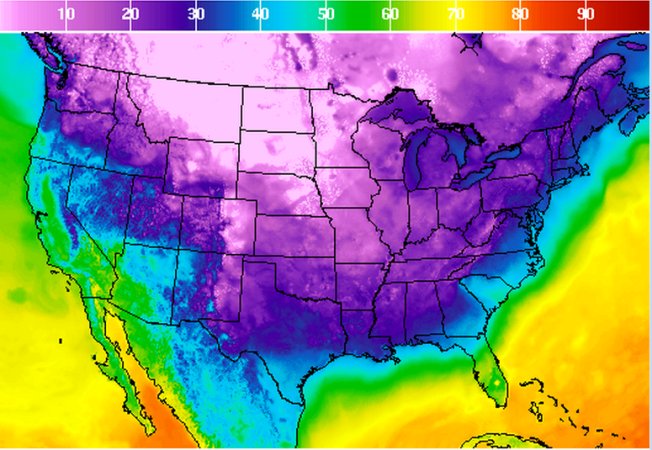

Another major threat to North Atlantic right whales is being struck by large vessels. Ship strikes killed at least 20 individuals between 1990 and 2010, according to NOAA Fisheries. In 2008, the agency set seasonal speed limits for ships 65 feet or longer along the East Coast, and claims there have been no whale-ship collisions since; presumably slower speeds give the whales time to get out of the way of the approaching vessels. Although the rule expired at the end of 2013, NOAA Fisheries has proposed to make the speed limits permanent.