Behold the Pegasus! In September last year, the US Army tested the drone as part of Project Convergence, a big exercise exploring future machines of war. A photo reveals its matte-black form stark against the sky, a red light glowing in the middle of an obsidian fuselage.

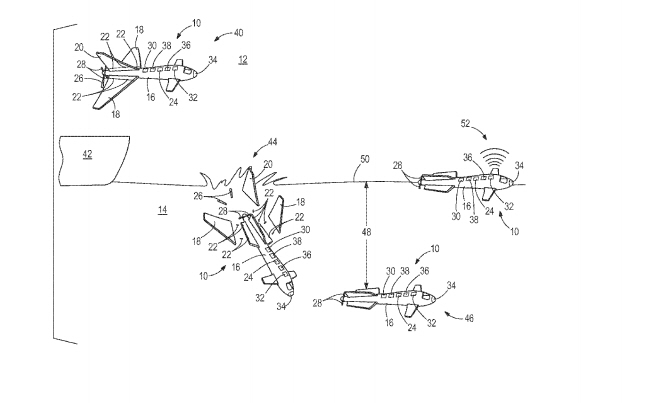

“These vehicles fit a new category of robotic systems,” Alberto Lacaze, president of Pegasus-maker Robotic Research, said in a release from the Army about the event. “They aren’t quite ground vehicles, they’re not quite aerial vehicles—they’re somewhere in between.”

The Pegasus family of drones comes in three sizes, ranging from 4 to 38 pounds. The electric drones are all designed to fly between 20-30 minutes—or to drive for several hours on the ground. In the photo above, the tracks it can cruise on are lifted up like guardrails around its rotors.

Endurance in the sky and on the ground varies with battery size and airframe. The light Pegasus Mini is listed as having only 2 hours of drive time, whereas the larger Pegasus III can travel for up to 8 hours.

[Related: The Army’s launching drones from dune buggies. Here’s why.]

Building a multi-modal drone comes with certain design trade-offs. The weight of tracks on a quadcopter can limit endurance in flight, while accommodating rotors on a tracked vehicle means a more spread-out body than normally seen on military ground robots. What the combined design promises is the ability to get above, around, under, and through obstacles.

On tracks, a Pegasus could roll through a culvert and then, once on the other side, take flight, signaling if the passage is safe for humans to follow. When equipped with sensors, the drones can record and transmit video to human operators. If a Pegasus scouts an area and is successfully recovered (not always a guarantee in war), that information can be uploaded and used to generate a 3D map of what it recorded.

[Related: Watch a fighter jet and drone make ‘wet contact’ for the first time]

As billed, the drones can also operate in areas without GPS. That’s key because GPS can be actively denied by enemies using jammers (or disabling satellites, should a war escalate to the exchange of missiles in orbit), and it can also just be passively denied, by operating in terrain like mountains or caves that make it hard to receive signals.

In such situations, a robot that can scout and map terrain could prove especially valuable, as it restores an understanding of the area to a military accustomed to operating with GPS. Like many of the technologies tested in Project Convergence, the Pegasus family will likely undergo future testing and evaluation to see if the military will adopt it. What it does promise is a way to get both a ground and aerial scout into the same body. And one version is small enough to fit on a backpack.