Climate change is a sprawling, complex problem. But there is an astonishingly simple way to make a difference: plant more trees. Trees scrub pollution from the air, reduce erosion, improve water quality, provide homes for animals and insects, and enhance our lives in countless other ways.

It turns out that ecosystem restoration is also an emerging business opportunity. A new report from the World Resources Institute and the Nature Conservancy says governments around the world have committed to reviving nearly 400 million acres of wilderness — an area larger than South Africa. As countries push to regrow forests, startups are dreaming up new, faster ways to plant trees. For some innovators, like NASA veteran Dr. Lauren Fletcher, that means using drones.

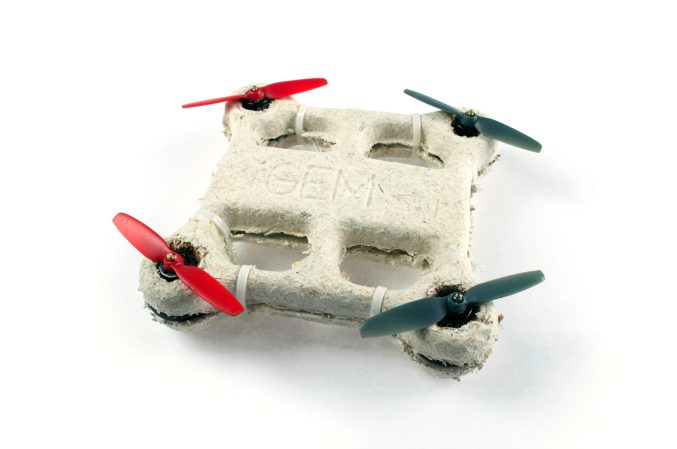

Fletcher said his conversion from stargazer to eco-warrior was driven by his worry about climate change, which has been dramatically worsened by deforestation. To tackle the problem, he created BioCarbon Engineering, which he describes as an ecosystem restoration company. Working with colleagues, he came up with a 30-pound unmanned aerial vehicle nicknamed “Robin.” It can fly over the most rugged landscapes on earth, planting trees in precise locations at the rate of 120 per minute.

Fletcher came up with his response to the problem of deforestation by identifying a major obstacle to planting new ecosystems. “I understood why forests were coming down so fast, but I was really puzzled as to why it was so hard to put them back together,” Fletcher said. “[I] realized very quickly that it’s because the state of the art [method] at the time was really hand planters, people with a bag of saplings on their shoulder going out, day after day, and bending over every 15 to 20 seconds and planting a tree, and it’s really hard, grueling work.”

Fletcher thought he could do better, so he put together a team of 12 experts with backgrounds in engineering, community development, ecology, biology and remote sensing. Step one was finding the right species of tree. “This is about restoration of local ecosystems, full stop. If you don’t get the biology side right, then you’re not a solution,” Fletcher said. Step two was building tree-planting robots.

BioCarbon Engineering’s fleet of drones flies ten feet off the ground, gently firing seed pods into the earth at the rate of two per second. That’s fast, but what’s most promising is the potential to scale. Fletcher says his goal is to plant 500 billion trees by 2050.

To meet that goal, he will need more than just drones. “Our solution is not a wholesale replacement of hand planting. There are times where hand planting is absolutely the right solution and sometimes the only solution,” said Fletcher, who wants to use planes and ground-based machines for planting in addition to drones.

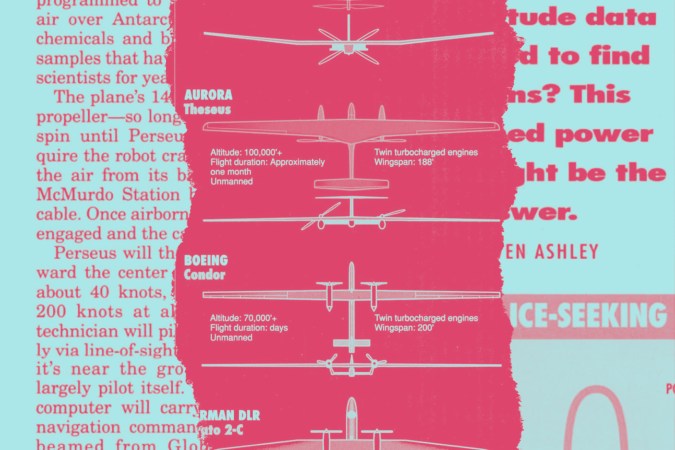

BioCarbon Engineering isn’t the only entrant into this field. Firms like DroneSeed in Seattle, Washington are developing plans to use drones to plant seeds, and already uses UAVs to spread fertilizer and spray herbicide. And UK startup Aerial Forestation is doing the same thing, but instead of deploying drones, they are relying on military transport aircraft. These and other firms are responding to a growing global push for reforestation outlined by the new report.

Fletcher is optimistic about the future of forests. “This isn’t just a convergence of technology,” he said. “It’s actually a convergence of social will and political power that are all focused on this global problem.”

Nexus Media is a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, politics, art and culture. Josh Landis and Owen Agnew contributed to this report.