Military airplanes that can accelerate through the sound barrier are relatively common. An F-16 and other fighter jets can do it. So can a type of U.S. bomber, the B-1B. But those planes are designed for fighting and bombing, not shuttling executives around. And the aircraft that carries the president, Air Force One, is a 747, an iconic but decidedly subsonic plane.

Recently, the Air Force took a small step towards exploring what a supersonic aircraft for government leaders could look like. In August, the military branch awarded three private companies contracts that total about $4.8 million—a small amount considering the eye-watering sums that accompany military aircraft (upgrading just one B-52 bomber, for example, will cost around $130 million). The contracts are for the companies to deliver information to the Air Force about supersonic executive transport concepts.

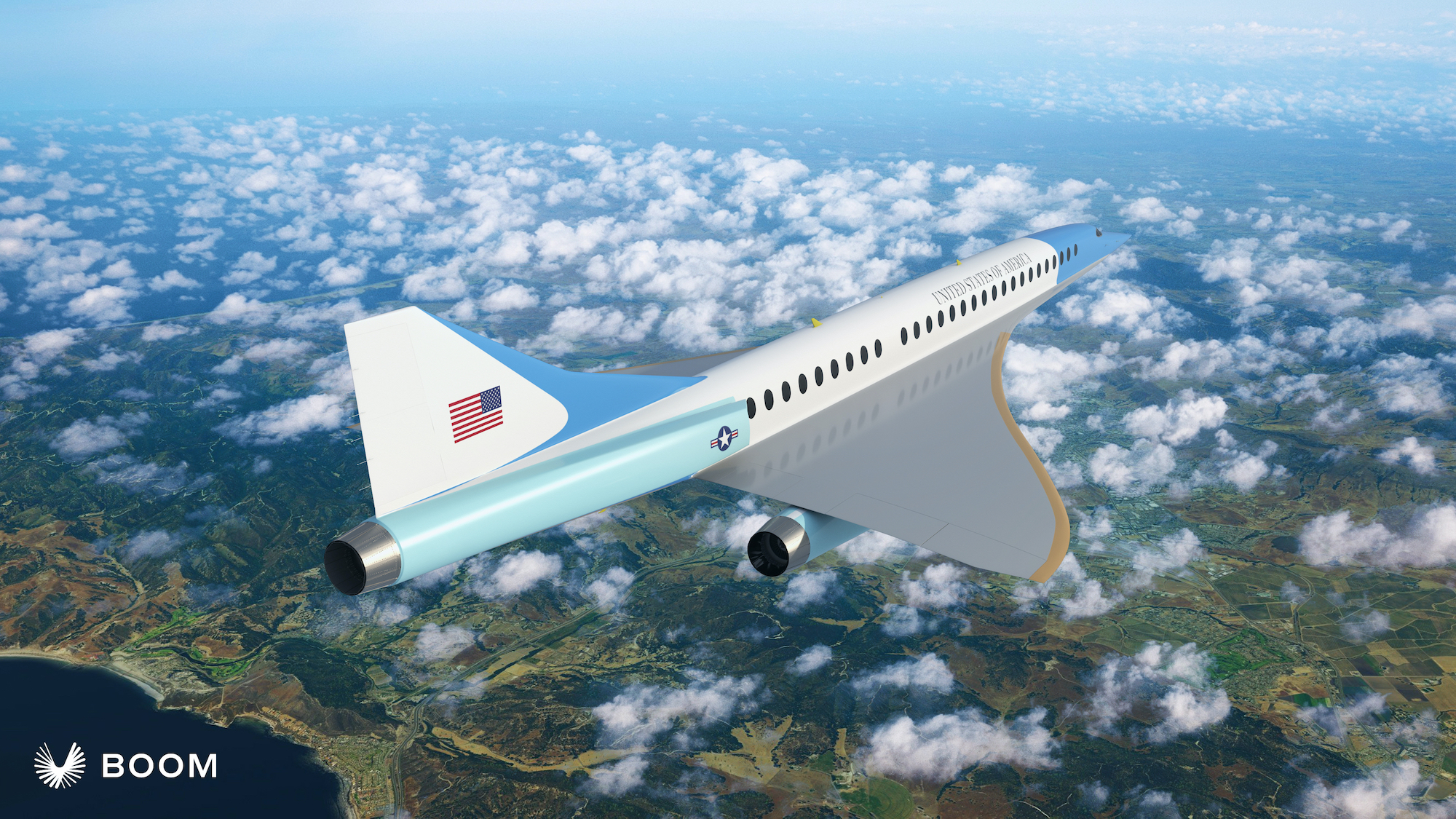

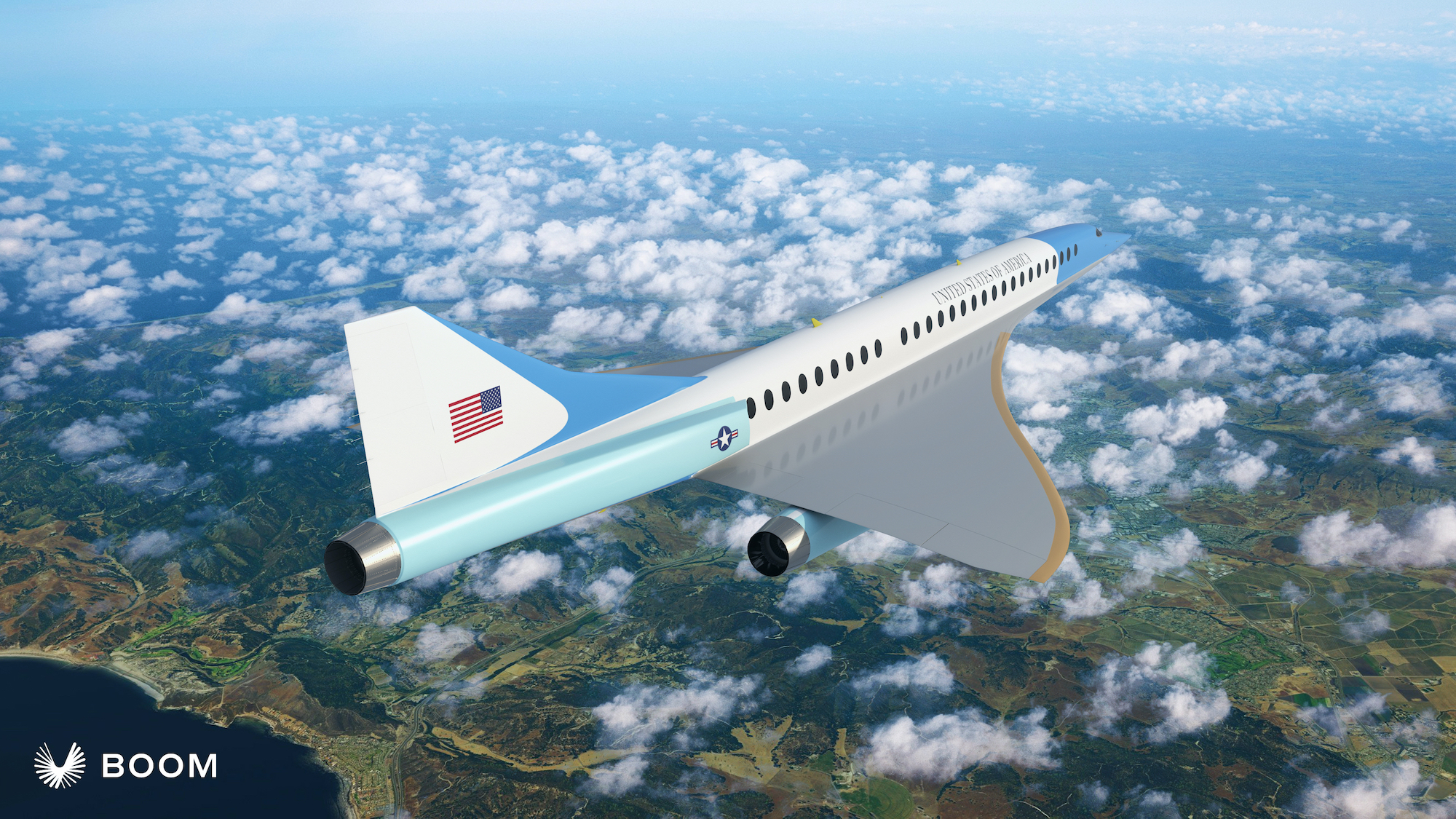

The three companies are Boom, Exosonic, and Hermeus, and they’re all working on different types of supersonic aircraft. Denver-based Boom, for example, envisions a Concorde-like airliner called Overture that could zoom people from Tokyo to Seattle in just 4.5 hours. Last year, Popular Science took an in-depth look at Boom and other companies that want to bring supersonic flight back for commercial or business-jet passengers—an idea that comes with serious economic, technical, and environmental challenges.

The relatively small Air Force contracts aren’t for the actual delivery of a finished supersonic aircraft. Instead, they’re for configuration concepts: these companies will deliver specs such as what the dimensions or weight of such an aircraft would be, its communications set-up, and how the cabin would be laid-out (the Air Force says it will receive a VR model of the interior space).

As for who a hypothetical jet like this might carry, a spokesperson for the Air Force’s Presidential and Executive Airlift Directorate notes via email that these concepts are for “executive transportation” and thus “potentially for our nation’s senior leaders.” The spokesperson also says that this project doesn’t affect the plans the Air Force already has in place for the next-gen Air Force One, which the military refers to as the VC-25B, and will once again be a Boeing 747.

One major issue with supersonic flight is the sonic boom an aircraft creates as it flies overhead, which can perturb people below. For that reason, civilian aircraft can’t break the sound barrier over the US; the aerospace industry is thus interested in creating a craft that can go faster than the speed of sound without making that boom. A notable project comes from both NASA and Lockheed Martin, which is working on an aircraft called the X-59 QueSST. That plane—still a work in progress in California—is intended to be a demonstrator craft that NASA will fly over the US to gauge public feedback in response to what the agency refers to as the plane’s “thump,” or quiet sonic boom. Interestingly, the X-59 won’t have a traditional windshield for the test pilot at the controls—they’ll look at a 4K monitor in front of them instead to see the scene in front of the plane. If successful, the X-59 project could help pave the way for relatively quiet supersonic flight over US soil.

Indeed, making supersonic travel less noisy is the stated goal of one of the three companies that the Air Force contracted for executive transport—Exosonic advertises an aircraft concept that would have a sonic boom that is “muted.”

Of the three companies, Boom is the one closest to unveiling any kind of hardware publicly. Next month, the company will unveil a demonstration aircraft called the XB-1, a new supersonic-capable plane that is one-third the size of what they hope their commercial airliner will be.

But projects like these take years, so members of the public—and government leaders—should expect to fly at traditional, subsonic speeds for the foreseeable future.