Tomatoes can be a bit of a pain. From their predisposition to blight to their heavy sun requirements and long, hard-to-hang vines, these delicious fruits aren’t always easy to grow—particularly in small spaces. Now, using the power of gene editing, researchers have produced tomato plants that grow as a bush, not a vine, presenting the cultivator (hopefully) with a bouquet of ripe cherry tomatoes.

“For a number of years now, we’ve known that we could modify specific genes to control flowering and makes plants more compact,” says Zachary Lippman, a plant biologist at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York State. But it took some time to figure out how to combine those traits into a small, high-yield tomato. Lippman and his colleagues published their results Monday in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

“All flowering plants have a universal system of genes that encode hormones that tell the plant to stop making leaves and start making flowers,” Lippman says. In nature, those two periods of growth are pretty balanced. But agricultural plant breeders place much more weight on the plant’s vegetative growth phase, when it makes leaves, since that’s how it gets big.

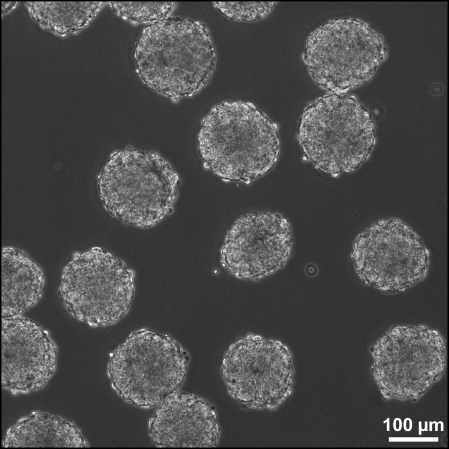

However, since flowering is what produces fruit and seeds—the yummy stuff—Lippman and his colleagues have been researching how to accelerate that phase too. In this work, they identify the third in a series of genes that need to be edited in order to allow faster flowering and fruit growth. The first two, which were already known, directly control rapid flowering and fruit growth. But the third, which they identified in this paper, actually controls stem length. By using CRISPR-Cas 9 to “turn off” all three of these genes, they were able to produce small tomato bushes that yield bouquets of cherry tomatoes in less than 40 days.

Humanity has spent the past few millennia genetically engineering crop species by breeding in desirable traits down the generations. This kind of breeding works by selecting specimens that have mutations which make them better food crops—for larger yield or fast growth—and breeding them intensively. These crops are good for growing on traditional farms.

But the way we live now requires crops that can grow in new environments and take new shapes. And since human agriculture needs to revolutionize quickly in order to reduce emissions and feed a growing world population while adapting to the impacts of climate change, those crops need to come to market soon, not in the decades-long timespan it takes to breed the old-fashioned way. That’s where gene editing comes in: Scientists can instantly trigger mutations that might take decades or longer to emerge naturally.

The team has nicknamed the plants “urban agriculture tomatoes” because they’re part of a broader effort to engineer crops for use in cities. These plants need to be compact and efficient, and able to grow in vertical farms rather than spread out across wide fields. The method his team developed is “very reproducible” in other plants, says Lippman, because the set of genes that control flowering are universal.

Tomatoes were an obvious first target for a few reasons, Lippman says. They pair with leafy greens in salads and sandwiches, for one thing. Those greens are the only plants currently being cultivated in vertical farms, which can be found in various locations across the United States and are considered a growth industry. Second, says Lippman, tomatoes—like other fruits—are high-value crops that are often grown in warmer climes and brought to the continental United States. Reducing the distance they have to travel to reach our plates could make a real environmental impact.

They also still need to be tasty. Lippman says he’s tasted the group’s results many times and the gene-edited fruit “tastes like a cherry tomato I like.”

Since the technique they developed can be generalized to other flowering plants, it’s possible that down the road we’ll grow bushes of everything from cucumber to kiwis. Hopefully they’ll be tasty too.