For two space architects who spent two months in a remote Arctic habitat to simulate lunar exploration, getting personal and spending time on leisure helped keep them happier and pass the time quicker, according to a new study.

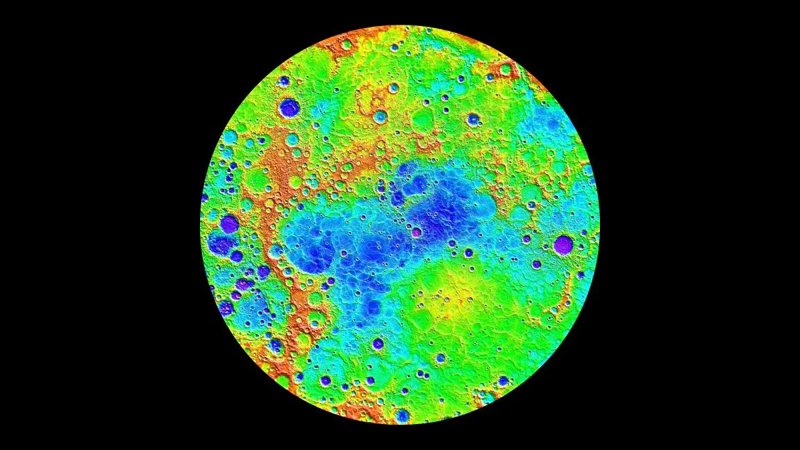

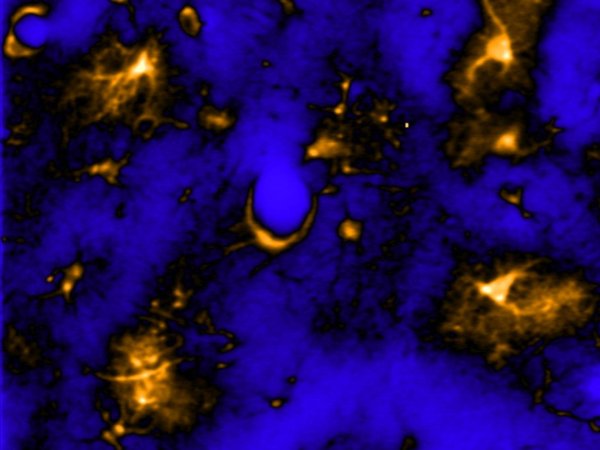

The study, published last month in Acta Astronautica, found that the two architects had an increasing desire for social connection over the course of the experiment, a 61-day mission in a small capsule-like habitat in Northern Greenland. The shelter, which they designed, is an egg-shaped pod that collapses using origami folds to become portable. Their only access to the outside world was a satellite phone limited to 160-character messages.

They didn’t increasingly feel more resigned, however, as might be expected. The voluntary social isolation that explorers deal with in spaceflight, typically with a known end date, may impact people differently than the isolation some experience in day-to-day life.

“Our research shows that being socially isolated and confined in an extreme environment when you are motivated to achieve a goal…might have fewer negative consequences compared with other episodes of social isolation and social exclusion,” says Luca Pancani, a social psychologist at the University of Milano-Bicocca in Italy and an author on the paper.

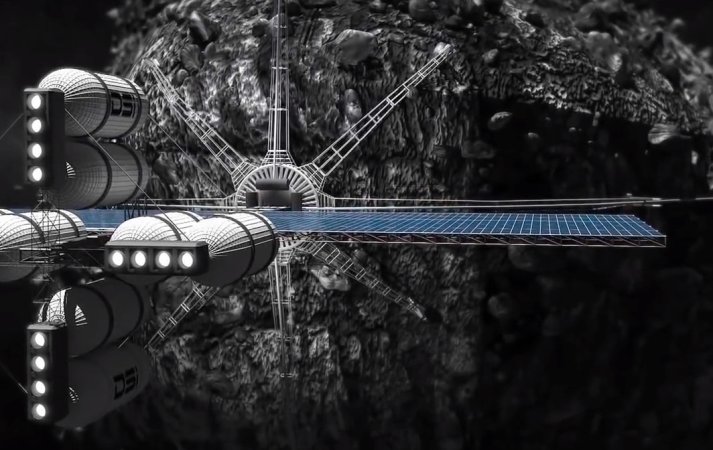

For the purposes of simulating a longer space mission, two participants is too few people to be realistic, says Peter Suedfeld, a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of British Columbia who has studied how people respond to space and other isolated environments and wasn’t involved in the study. But the 61-day duration is more accurate than many other too-short experiments, because NASA plans to have a sustained presence on the moon.

“There’s a serious question as to the validity of simulation studies,” Suedfeld says, because the conditions of space exploration can’t really be mimicked on the ground. Though he thinks there’s still a place for them in space research. Essentially no psychological research has been done on astronauts on the moon, so good simulations are useful in studying how people might react during real lunar missions.

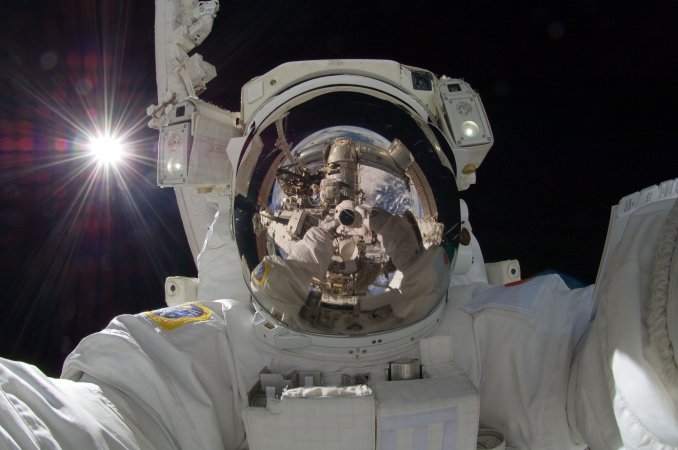

In this experiment, the participants had to suit up for the cold whenever they left their small pod to collect ice for water or to film the area for a documentary.

As for the finding that time flew while the architects were having fun—or at least doing anything recreational—that has been well documented in other situations, he says. This happened while the architects watched films together or exercised.

The Chinese Space Agency is doing a lunar simulation as well, though it isn’t focused on the outside environment at all, Suedfeld says. By contrast, many other experiments have tried to simulate Martian conditions such as the Hi-seas project in Hawaii and Russia’s Mars 500 experiment, which was entirely indoors in Moscow.

Even though there were only two participants, the study was conceptually robust, says Valerie Olson, an environmental anthropologist at the University of California Irvine, who has authored a book on the culture of spaceflight and wasn’t involved with the work. It is a nice example of exploring the relationship between social and psychological factors, she says.

[Related: We could live in caves on the moon. What would that be like?]

For a long time, the psychological study of individual astronauts has been central to the study of human spaceflight. But in the last decade or two, more emphasis has been put on social psychology and more qualitative sciences, she says. In this case, the study analyzed the results of a regular, self-reported psychological questionnaire. It found that when the architects–who knew each other well prior to the mission–talked about personal matters, that seemed to lessen feelings of resignation and hopelessness while increasing their desire for social contact.

Olson has a general criticism for simulations in extreme or isolated environments. Psychological researchers are often interested in finding universal human traits—attributes and experiences that can be generalized for large groups of people. But humans are “both biological and cultural beings,” Olson says, who can’t be separated from their cultural upbringings. So how individuals will react to these extreme environments depends a lot on what they think of the environments to begin with. She’s curious about the participants’ backgrounds: “Two young Danish male architects—what are their attitudes and experiences about the Arctic or about coldness?” she says.

The Arctic is typically described by experts in this kind of research as “as being a place of isolation and extremity,” Olson says. But the Arctic is also home to many indigenous peoples—for them, what seems extreme to Western researchers is home, and what seems like isolation is just a smaller social circle. The barren, rugged, unforgiving landscape could feel alien to one group and comforting to another.

Astronauts, including those from the US and former Soviet Union, have held different attitudes about what was good and bad about their time in space and different values about what space means to them, Olson says. She’s interested in what emerging space agencies, especially in the global South will focus on—how different cultures will explore the questions of “what is loneliness, what is sociality, what is belonging?”

If humans are to thrive in space, they may need to give more merit to what the astronautics community calls the squishy stuff—how people feel and what is meaningful to them.

This story has been updated to clarify there have been no psychological studies of astronauts on the moon.