Popular Science’s Play issue is now available to everyone. Read it now, no app or credit card required.

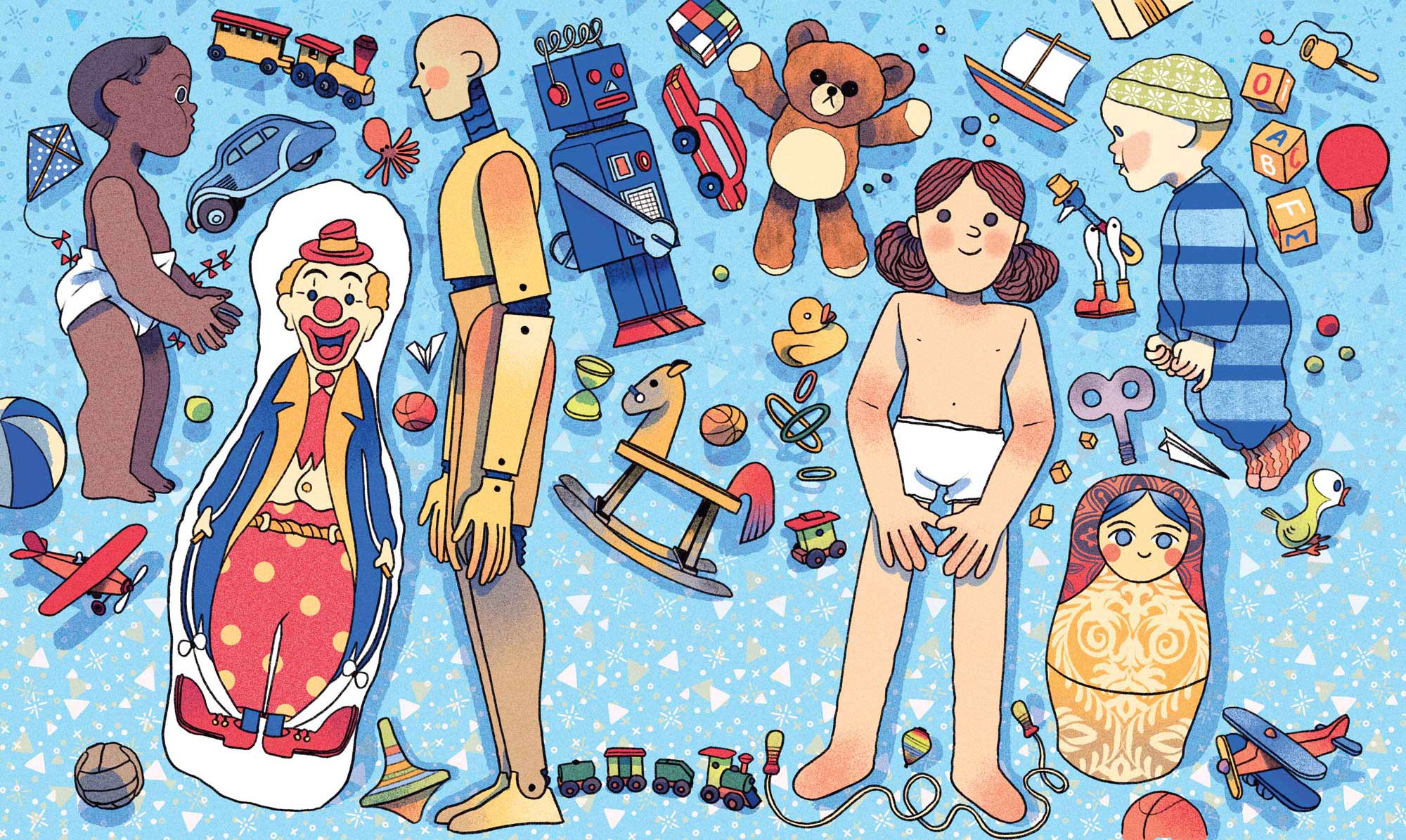

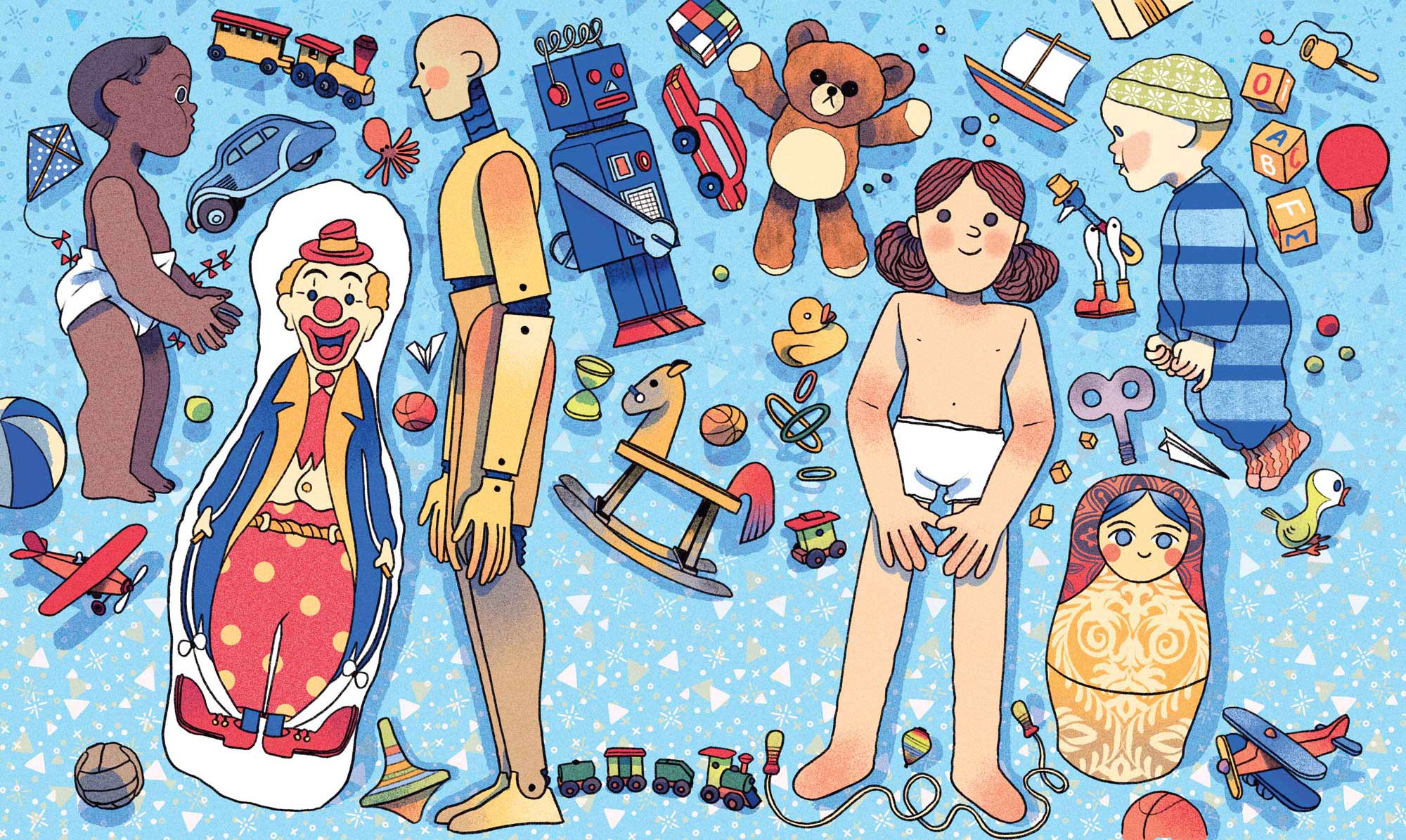

When scientists bring dolls into the lab, the toys transcend their role as playthings. They can expose racism and unleash aggression. The humanoid forms are easy to identify with, allowing them to serve as scientific stand-ins and therapeutic companions. Their familiar anatomy is also ideal for plotting out technical reference points. From creepy to cute, these five figurines have powered decades of research and innovation.

Reveal racism

African American psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark used sets of toy babies—some with white skin, some with brown—to understand how black children living under segregation in the 1940s developed their sense of self. Black kids presented with both options preferred the pale doll; some even cried when asked which looked like them. The Clarks took this as evidence that youths internalized the social values of their environment: They saw themselves as inferior because of their skin color. The tests impressed attorneys in the famous Brown v. Board of Education lawsuit, where Kenneth testified that segregation led to self-hatred. The Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling on that case finally integrated schools and spurred a growing movement for civil rights.

Probe Violence

In the early ’60s, the blow-up Bobo helped psychologist Albert Bandura investigate how children learn from adults. At the time, his peers surmised that people made behavioral choices based on perceived rewards and punishments. Bandura suspected otherwise. His young study subjects instinctively imitated grown-ups who were rough with Bobo, hitting the clown with abandon. Kids were most likely to attack when they saw male adults do so, perhaps because society framed men as ideal role models for aggression. Since test subjects didn’t see violence result in prizes or penalties, Bandura concluded that we sometimes learn complex behaviors by simply copying others. Bobo’s bonks still resonate in research about the impact of violent video games.

Test safety

The history of car safety is splattered with gore. Early automakers dropped cadavers onto windshields to see if their skulls would crack and smashed anesthetized baboons into airbags. That started to change in 1949 with Sierra Sam, the first-ever crash-test dummy. But Sam was tall and had bendy rubber joints, which skewed results, and the lack of industry-standard dummy specs made tests difficult to replicate. The solution was 1972′s Hybrid II, whose weight and height perfectly matched the 50th percentile for American men. Engineers created new instruments to measure strikes to its lifelike joints and posture. Hybrids now come in a variety of sizes, so manufacturers can bring an entire faux family along for the ride.

Support survivors

Most dolls don’t have anatomically correct genitals. But some investigators keep a collection of accurately outfitted toys whose mission is to help survivors of abuse disclose what happened to them. These so-called anatomical dolls lend specificity to kids’ testimonies. In the 1970s, pediatricians, social workers, and psychologists began conducting in-depth dialogues with youths they suspected had been molested. When they weren’t forthcoming, the realistic models encouraged them to reveal more. In one study, the toys made children interviewed about possible abuse twice as likely to name a perpetrator and three times as likely to provide detailed descriptions of their experience. There are, however, ongoing debates about whether the floppy props might spark false claims.

Give comfort

Dementia-unit staff increasingly use ersatz infants to help residents with Alzheimer’s disease. The trend began in the ’90s, after case studies showed improvement in symptoms thanks to dolls. “Within days, this withdrawn, frustrated, and depressed individual gained a new sense of meaning to her life,” wrote one researcher in 1990. In a 2006 pilot study, nursing home employees reported residents with toy companions seemed calmer and happier, and had an improved sense of purpose. In a 2014 experiment, those receiving doll therapy were less agitated when nurses left the room. Psychologists think the playthings may serve as transitional objects that help patients relate more comfortably to the world around them—similarly to a child clinging to their favorite blanket.