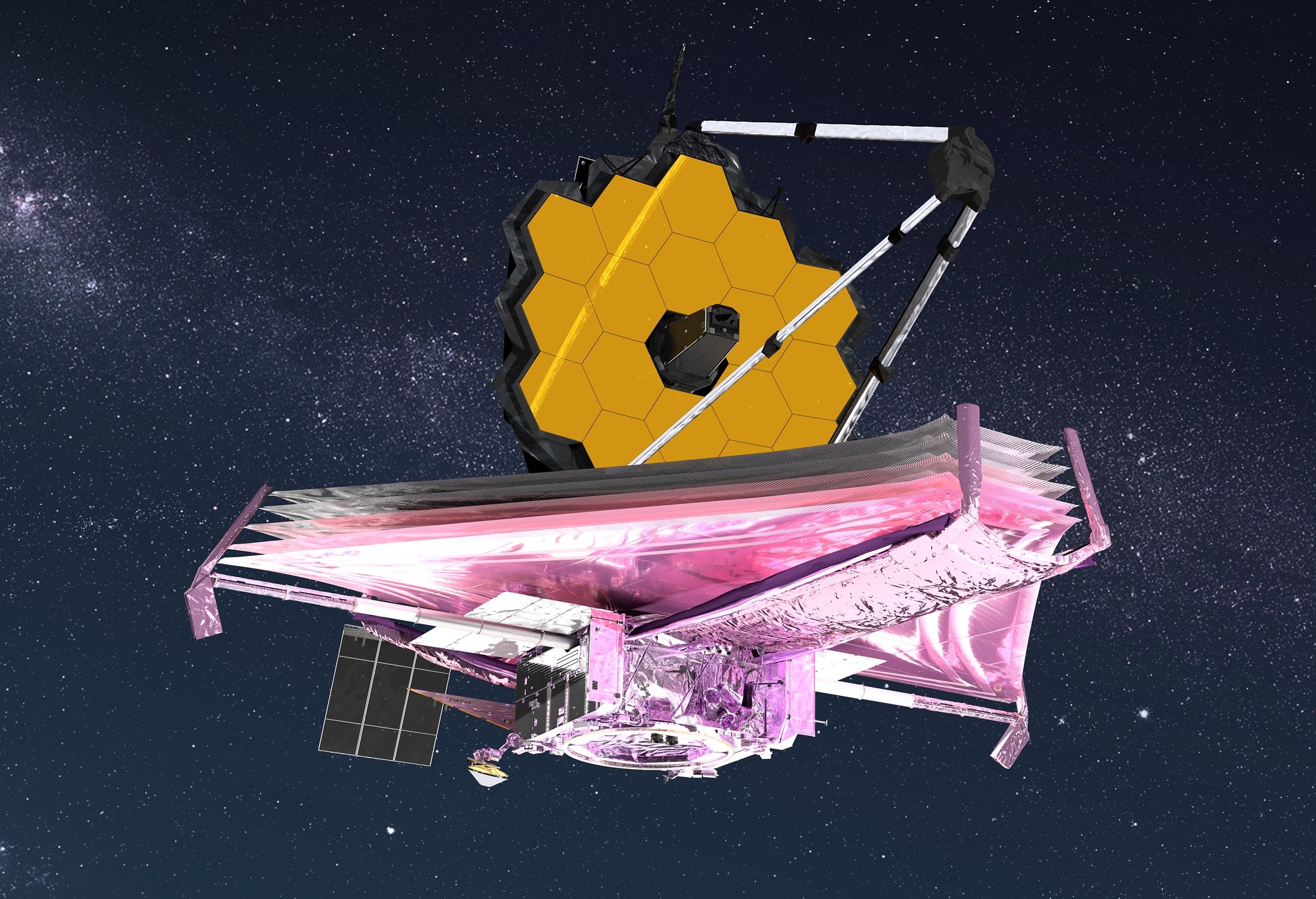

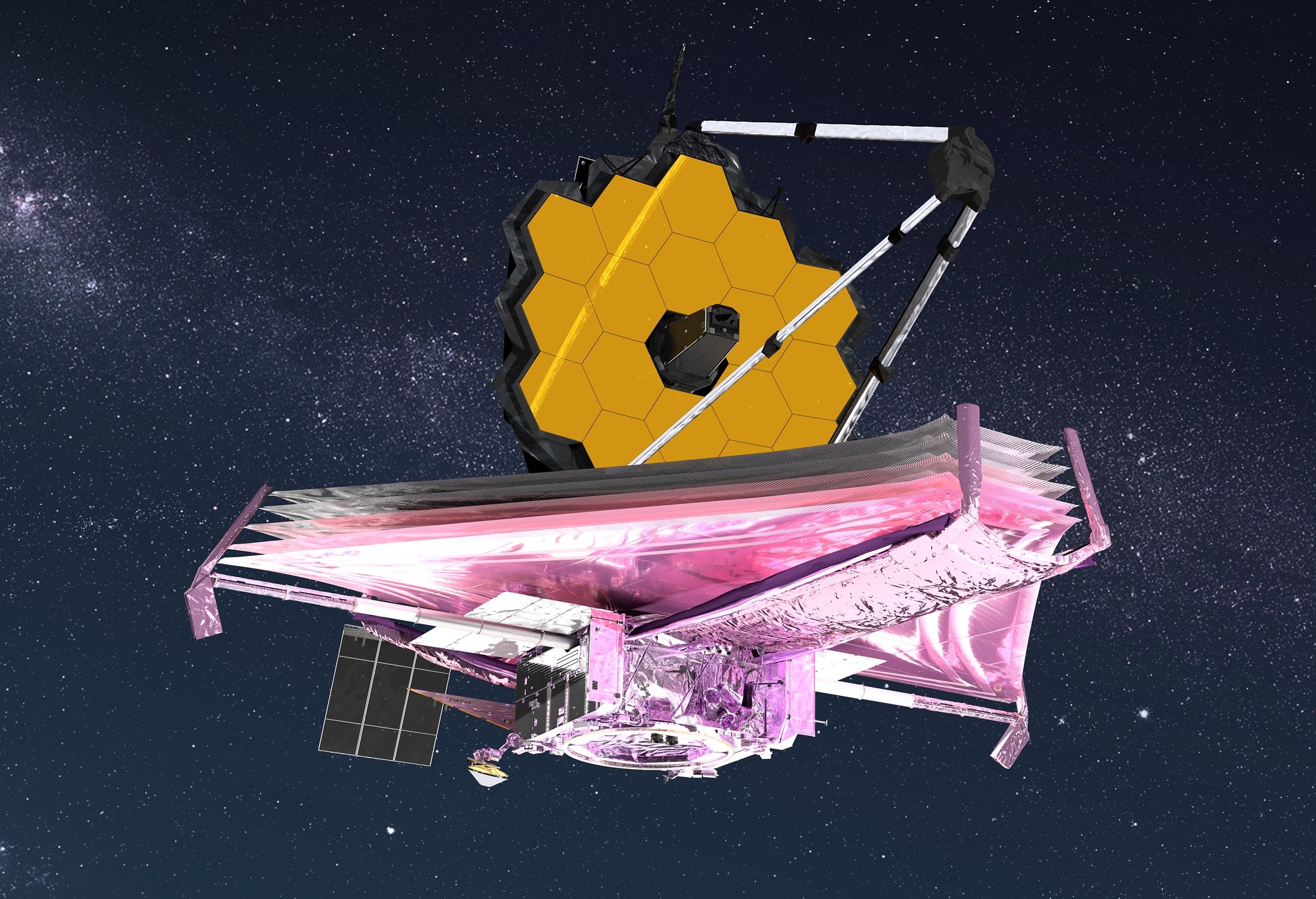

Our tiny corner of the cosmos has just gotten bigger, brighter, and bolder, and it’s all thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). NASA just dropped some of the most high-definition images of the universe ever taken. Although the telescope began science operations merely six months ago, its first batch—including five neighboring galaxies called Stephan’s Quintet and the Carina Nebula, a gaseous expanse where stars are born—are among the most stunning celestial pictures yet made.

Inspiring wonder in space-lovers around the world is harder than it looks. A lot of work goes into making sure these cosmic close-ups photos are not only beautiful, but they reflect the astronomy community’s scientific priorities. So what exactly goes into crafting JWST’s next picture-perfect photographs?

The answers to these questions lie within the differences between JWST and its predecessor, the 32-year-old Hubble Space Telescope. The two have vastly different capabilities: Hubble, for one, mostly takes images inside visible and ultraviolet wavelengths. JWST captures its targets in the infrared color spectrum, light waves that are invisible to the naked eye. To create the spellbinding scenes that just debuted, scientists had to process and fill these images with color. This also explains why many pictures of the same cosmic object can look vastly different, depending on how astronomers choose to shade them.

Additionally, due to the size of its mirrors as well as its ability to see infrared light, JWST is able to peer further back into time than Hubble. According to the space agency, you can think of Hubble as able to only see “toddler galaxies,” while JWST can spy “baby galaxies.”

[Related: There is no Planet B]

During a NASA press conference held on Tuesday, Eric Smith, the program scientist for the JWST mission, said JWST’s first photos are especially phenomenal because they were technically nothing more than practice runs. It seems astronomers may have been too conservative in picking early telescope targets, because when planning these projects they weren’t prepared for how good the images would be, he noted. “We’re making discoveries and we really haven’t even started trying yet, so the promise of this telescope is amazing,” Smith said.

But with the proof of the current images, Smith hopes that in JWST’s second scientific cycle, “people will be much more adventurous because they now know just how good the facility is.”

JWST can also gather more data more swiftly than Hubble. Klaus Pontoppidan, program scientist for the JWST mission, told reporters that NASA scientists spend weeks, on average, downloading and processing individual images before they’re transformed into the depictions that are released to the public.

Hubble transmits about 120 gigabytes of science data to Earth every week. Over the next few days, JWST will release roughly 50 terabytes of data—more than 400 times Hubble’s weekly transmission—to the public. The new image of JWST’s deep field, which President Biden unveiled Monday, was created from a composite of images at different wavelengths and took about 12.5 hours to complete, according to NASA. Alternatively, Hubble’s deepest fields took weeks to put together.

While NASA has not yet released a fresh target list or a timeline for new images, agency officials reported that the mission team would focus on investigating the exoplanets in the Trappist-1 system during JWST’s first full year of operation. The telescope will undergo “atmospheric reconnaissance” in a bid to learn more about the system’s atmospheres, habitability, and planetary formations.

[Related: The James Webb Space Telescope survived its first collision]

The telescope is expected to last for a few decades. As long as it has enough fuel, and withstands the harsh realities of life in space, it should be able to operate at full capacity for that duration. During its time gazing at the stars, it will act as a sort of time machine, allowing astronomers a small sparkling window into what the universe looked like more than 13 billion years ago. Moriba Jah, an associate professor of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics at The University of Texas at Austin, said the measurements the telescope beams back will not only provide the evidence needed to peer into the universe’s origins, but will inform future advances in astronomy and aerospace engineering as well.

“What we really want is to not only understand what happened, but predict what’s going to happen in the future,” he says.“If we can predict more accurately, we can make better decisions to make sure that we as a species can actually thrive in perpetuity.”

While JWST’s future looks bright at the moment, astronomers warn that space is far from empty: it’s unpredictable. Right now, the telescope lies at the second lagrange point (L2), a stable gravitational area about a million miles from Earth where objects like space junk or micrometeoroids tend to drift. But Jah points out the observatory could be wrecked in a moment, if a large piece of a rocket, a space rock, or small satellite were to collide with JWST.

Yet with so much hinging on the telescope’s continued success, it’s almost guaranteed that JWST will continue reaching for the horizon, pushing the boundaries of stellar observation for years to come.