The subtitle of astronaut Mike Massimino’s new memoir, Spaceman: An Astronaut’s Unlikely Journey to Unlock the Secrets of the Universe, hints at two things: his bootstrap beginnings as a nerdy kid with bad eyesight, and the eventual god’s-eye scope of his work.

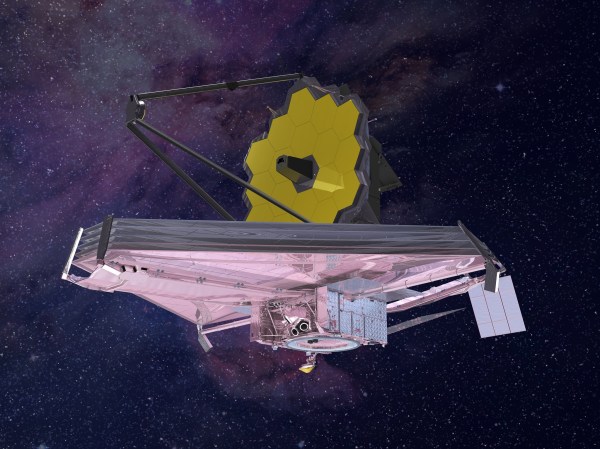

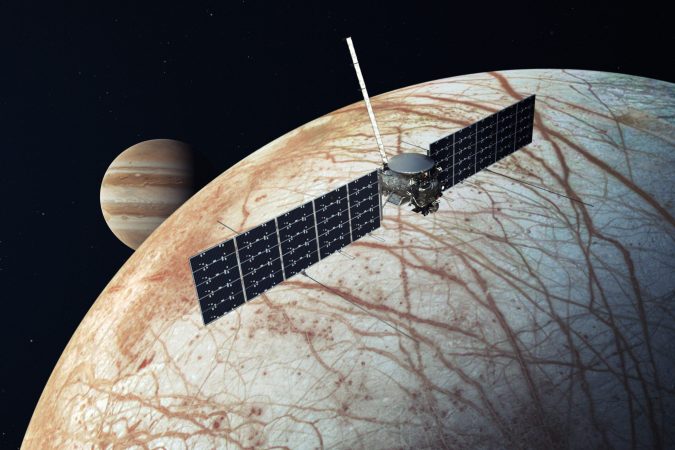

In case you don’t know, Massimino belongs to a very elite club, even among spacewalkers. He’s one of the few people to have traveled to—and repaired—the Hubble Space Telescope, which orbits Earth 353 miles overhead, peering into the beginnings of the universe.

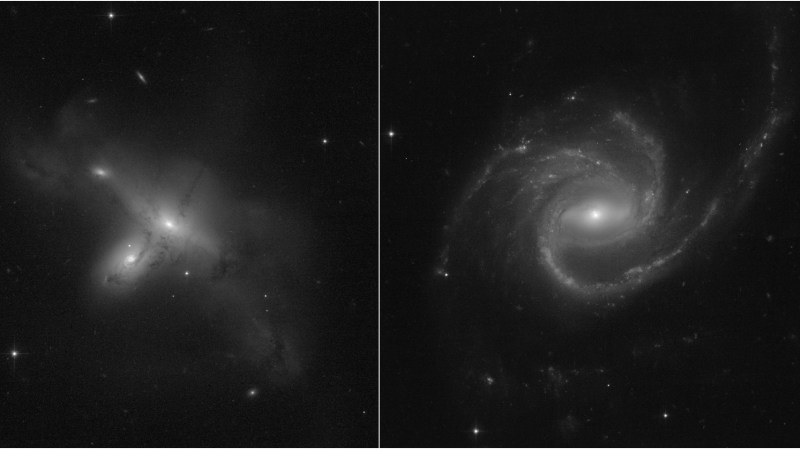

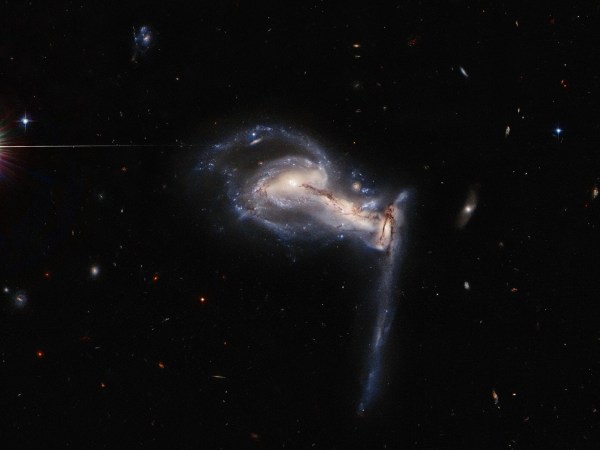

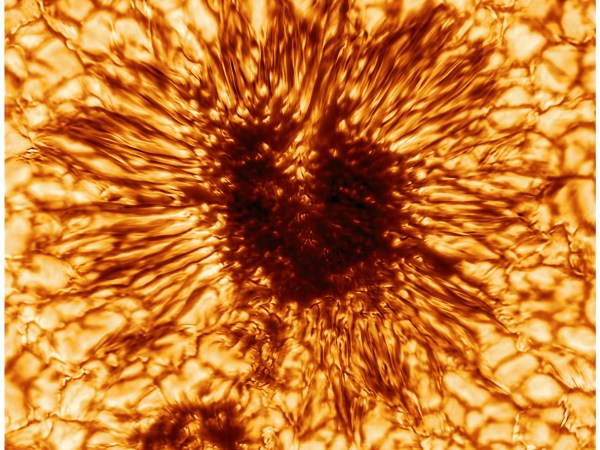

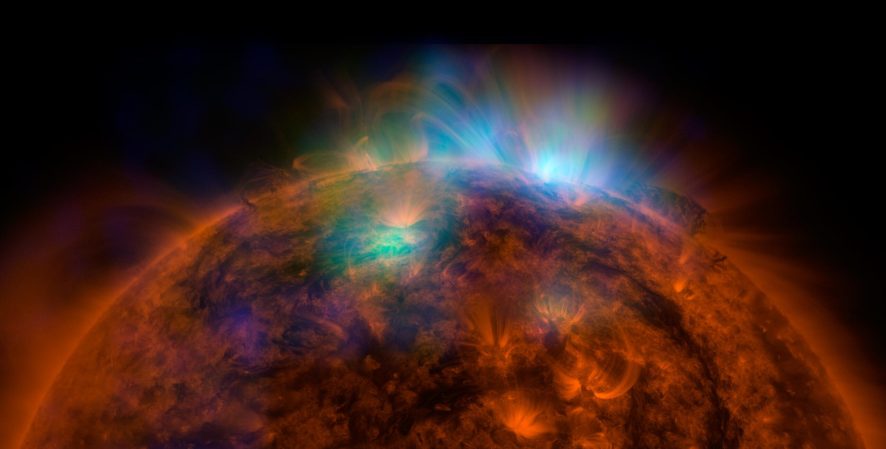

Everyone has, of course, seen Hubble’s break-the-Internet images of towering nebulae, crablike galaxies, and one very acned red-spot on Jupiter. Well, each one should probably come with a Mike Massimino photo credit. After all, the guy risked his life to make sure we have them.

In 2009, Massimino and fellow Atlantis shuttle astronaut Mike Good spent 10 hours tethered to the broken Hubble, trying to repair its imaging spectrograph—an instrument that depicts black holes and distant alien planets. After various tools failed them, Massimino had to forcefully rip off a broken handrail to clear it from blocking the spectrograph, all while traveling 17,500 miles per hour, in 97-minutes laps of the Earth, plunging in and out of daylight and darkness.

It was a Christopher Nolan moment, a remarkable feat made more so by the fact that it should never have even been required. The spectrograph “was never meant to be repaired,” Massimino writes. “The Hubble’s instruments were designed to survive the violence of a shuttle launch and the brutal conditions of space. They weren’t designed to be opened up. By anyone. Ever.”

Massimino’s memoir is engaging and nerdy, well written and personable—like the man himself. (If you don’t believe me, check out his recurring role as himself on “The Big Bang Theory.”) It also covers a generation’s worth of space adventure—its triumphs and tragedies—starting with one of the most horrific as he recalls watching, in 1986, as the Challenger space shuttle breaks apart, 17 seconds into its flight, live on national television. It claimed the lives of all seven crew members aboard.

At the time, Massimino himself was trying to decide whether NASA’s astronaut program was worth it, whether he should pursue the academic safety of a PhD or undergo years of difficult training for a slim shot at traveling to space like his childhood heroes. In 1969, at age six, he had watched as Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong walked on the Moon; he remembers standing in his yard and looking up, thinking, “Wow there are people up there walking around.” But it was Challenger that changed him. “I knew right then I wanted to be a part of something worthwhile,” he writes. “You only have one life; you have to spend it doing something that matters.”

What he accomplished ended up mattering to quite a few in the science community and to the rest of us. And ironically, the man who fixed the now 26-year-old Hubble nearly didn’t get the job—because of bad eyesight. Back in 1989, when he first applied to NASA, his eyes were so weak and lacked 20/20 focus that he was rejected despite being an otherwise ideal candidate. A second try, in 1991, led to the same rejection. But that year a NASA flight surgeon offered advice: try orthokeratology. It’s a therapy that involves wearing a hard plastic contact lens pressed against your eyeball until it flattens out.

Such a challenge would seem too much for most people. Thankfully, Massimino is not most people. To him it was just an obstacle. “I was ready to take on anything if I was that close to making my dream come true,” he writes. However, he soon learned that “once you took the lenses out, after a couple of days your eyes would go back.” The treatment also damaged his eyes. Still he persisted. He found a doctor who repaired the damage and trained him to relax his eye muscles, which improved his eyesight, enough so that in 1996 NASA accepted him to its astronaut corps, where he would wrack up near combined 24 days in space, until he retired in 2014.

In addition to his “unlikely journey” to space, Massimino’s book offers novelesque glimpses at the ups and downs along the way: His senior year at Columbia University, where he met his wife Carola. The birth of his children. The loss of his father—his biggest supporter. Before he joined NASA, he worked on robotics at IBM in New York City and each day after work popped in a VHS of The Right Stuff, which inspired him to keep moving in that direction.

One of most enlightening aspects of Spaceman is learning about the staggering amount of training an astronaut needs. It includes not weeks or months, but years in places like the Neutral Buoyancy Pool, practicing space walk maneuvers until they become muscle memory. There are years of fighter jet flying, and endless classes in engineering and math. It makes you appreciate the dedication that each crew member must possess to fly to space maybe one, two,or three times in their entire lives. It’s inspiring to think about people who train for 20 years for a total of two months worth of work. And there’s always that chance those 20 years will lead to you dying atop a rocket.

Needless to say, this career is not for everyone. It’s for the super elite (that’s why Tom Wolfe called it “The Right Stuff”). Luckily for science and humanity, there are men and women who are up to the challenge and who are willing to risk their lives in the name of exploration. While they may not have super powers, they do have a superhuman determination to go to space, no matter what the cost.

In 2003 that cost hit Massimino—the NASA community, and the nation—very hard once again. That February, the Columbia space shuttle disintegrated over Texas and Louisiana as it re-entered Earth’s atmosphere, killing all seven crew members. Massimino was with his family in Houston at the time, nowhere near the Kennedy Space Center control room. “I felt completely helpless,” he writes. “I felt like I should be in Florida with the families. I wanted to wake up and find that the whole morning had been a nightmare. We lost seven members of our family that day.” He coped with the loss by joining the investigation committee to determine what happened. It found that foam insulation broke off the shuttle, hitting the wing, which damaged its protective carbon heat shield, letting super heated gases enter the wing and completely erode it. The commission used the shuttle Enterprise to conduct research on the wing. Enterprise now sits at The Intrepid Sea, Air & Space museum in New York City, where Mike also serves as senior space advisor.

It’s clear from his telling that Massimino loves space, the community and family who belong to it, and in particular the Hubble Space Telescope for what it stands for in his thinking. Working on something like Hubble, and what it gave the world, was the reason he worked so hard for so long. “Exploration is what we do,” he writes. “It’s a basic human need—understanding what’s happening at the other end of the galaxy is a path to understanding ourselves, who we are and why we’re here….[T]here was no question, it was worth the risk.”