A molecular imaging study has pinpointed a set of biological markers that could help diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder more accurately, and might even lead to a pharmacological treatment in the future.

The research, published online today in Molecular Psychiatry found that people with PTSD have a greater number of CB1 receptors, cannabinoid protein receptors, and a lower concentration of one of the neurotransmitters that binds to them, anandamide. This provides empirical evidence for the theory that marijuana, which also binds to the cannabinoid system, can help alleviate some of the symptoms of PTSD, although the paper doesn’t recommend it as a treatment option.

Animals studies have found that chronic stress decreases the concentration of anandamide, an endocannabinoid neurotransmitter nicknamed “the bliss molecule” that has a very similar chemical structure to THC. Recent research has suggested that the endocannabinoid system might play a part in working through traumatic memories.

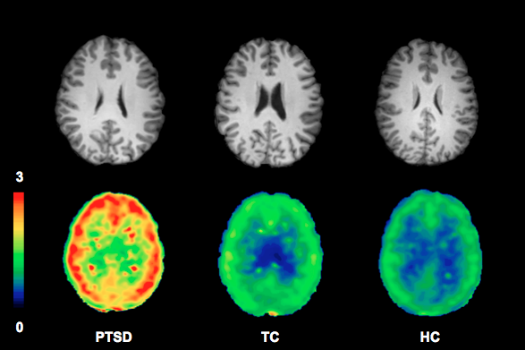

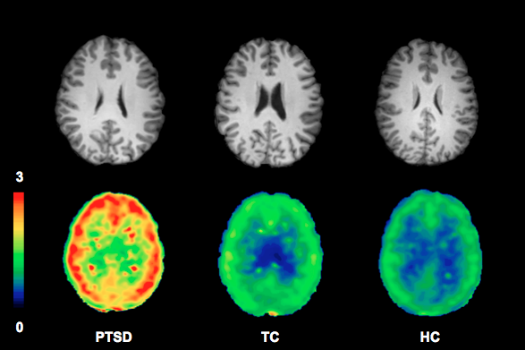

Endocannabinoids bind to two types of receptors throughout the central nervous system. Cannabinoid type 1 receptors, or CB1 receptors, help mediate various processes including mood, appetite and memory. People with PTSD had significantly more of these receptors in their brain compared to the study’s control group, including those who had been exposed to trauma but didn’t develop PTSD.

When the brain identifies too-low levels of anandamide, it increases the number of CB1 receptors in response to ensure that it can grab them all. It’s unclear whether a greater availability of CB1 receptors puts people at risk for PTSD, or if it’s a result of the condition, according to lead author Alexander Neumeister, a professor of psychiatry and radiology at the New York University School of Medicine.

Using brain scans that illuminated CB1 receptors, the study looked at the brains of 60 volunteers, some with PTSD, some with a history of trauma and some with neither. Women had higher levels of CB1 receptors in brain regions associated with fear and anxiety, consistent with the fact that women are much more likely to develop PTSD than men. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD, 10 percent of women develop PTSD, compared to 5 percent of men. Scientists can’t really explain why yet. Neumeister says it could be a biological phenomenon that women have higher levels of CB1 receptors and are therefore at greater risk, but it’s most likely a consequence of trauma.

In general, scientists aren’t sure why some people develop PTSD in response to traumatic events, while others do not, and so it remains a difficult condition to diagnose. “In most cases [experiencing trauma] does not change the life of people in a fundamental way, but there’s an important sub-group out there that when they experience trauma, it changes their life,” Neumeister explains.

Ideally, treatment should begin as soon as possible after a traumatic event. With an objective biological marker, the condition could be more rapidly diagnosed, so that patients could begin receiving treatment sooner. By looking at CB1 receptors, anandamide and cortisol levels, Neumeister and his team were able to correctly classify 85 percent of PTSD cases.

This could also lead to a pharmaceutical treatment for PTSD. “What we have currently doesn’t work. That’s the sad truth,” Neumeister says.

“There’s a consensus among clinicians that existing pharmaceutical treatments such as antidepressant simple do not work,” he said in a press statement. “In fact, we know very well that people with PTSD who use marijuana — a potent cannabinoid — often experience more relief from their symptoms than they do from antidepressants and other psychiatric medications.”

Neumeister isn’t pushing for smoking pot to combat the symptoms, though. “I’m very much an advocate against smoking pot as a treatment for PTSD,” he says. That’s partially because chronic marijuana usage has been found to a decrease the amount of CB1 receptors in the brain, in effect mimicking PTSD, increasing anxiety and irritability.

Instead, he’s focusing on developing a medication that could block the degradation of anandamide, balancing the endocannabinoid abnormality in the brains of people with PTSD. He’s still waiting on funding to start clinical trials, although he has completed several animal studies. He says this study shows that the animal models can easily be extended to humans, which isn’t always the case. “The beauty of these results is we could replicate something in living people with PTSD.”

His research has piqued the interest of the Department of Defense, a potential funder with a huge stake in finding effective treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, between 7 and 8 percent of the U.S. population will have PTSD at some point in their lives, and as many of 20 percent of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan deal with it.