THE FIRST TIME I get high on ketamine, I’m not sure I’m doing it right. The setting is nice enough: I’m tucked beneath a gray weighted blanket, reclining on a creamy leather chair. Headphones deliver the sort of playlist you’d find by searching for “meditation” on Spotify, and a mural of a gorgeous forest is the last thing I see before putting on a silky sleep mask. A therapist sits a few feet away, ready to provide reassurance if I need it. Down the hall, a friendly nurse practitioner is on call with Tylenol and gluten-free pretzels if I feel a little peaky when the session finishes, plus anti-anxiety medication if the sensation crosses into a little more than peaky. I am warm, safe, and supported.

Am I high enough, though? Should someone be saying something? Has it started? Am I ruining things by expecting something to “start”?

I came to Field Trip, a psychedelic clinic in midtown Manhattan, to try to vanquish post-traumatic stress disorder resulting from an abusive relationship that ended years ago. Ketamine’s on-label use is for surgical anesthesia, but over the past two decades, neuroscientists and psychiatrists have found it remarkably effective in treating symptoms of depression. Subsequent studies have also shown its promise with other mental health problems such as anxiety, substance abuse disorders, and PTSD.

In operating rooms, anesthesiologists characterize the drug as dissociative—distorting perception of sight and sound to the point of temporary oblivion—yet when it’s shot into my arm for the first time I remain decidedly associated. I feel woozy and relaxed, and the vague patterns of light and color I’m used to seeing when I squeeze my eyes closed are more vivid than usual. Still, all I can think about is that I’m supposed to be viewing my trauma with a new lens: seeing what I did and what was done to me from some great protective height. Turning inward will, I hope, empower me to banish whatever monsters I might find there. But right now, all my inner self has to say is, I am probably doing ketamine wrong.

After about an hour spent debating whether I should speak my misgivings out loud, my therapist gently invites me to “return to the space.” Over a cup of turmeric tea, I sheepishly admit that I fear I wasted my first of six prescribed “experiences.”

They assure me that this is common among their clientele so far. Field Trip opened its first clinic, in Toronto, in March 2020, to treat depression and other mental health problems, and has operated in New York City only since the following July. With my sessions straddling the turn of 2021, I’m working through a protocol the team there is still studying and adjusting.

To the average person, what Field Trip is doing may seem like a fringe practice, but it isn’t, strictly speaking, all that new. Research on how psychedelic experiences may relieve mental health conditions dates to the middle of the 20th century and stems from spiritual and cultural practices centuries older than that. Ketamine’s ability to cure patients let down by traditional antidepressants and therapy emerged in the late ’90s, and since then, investigators have worked steadily to hone their understanding. It’s helped a lot that the drug, approved as a general anesthetic in 1970, is easy to get—unlike more heavily regulated compounds like LSD or psilocybin. That availability, though, has also made it possible for commercial use to outpace scientific consensus. Online directories indicate that at least 75 US clinics offer the substance to the public.

[Related: What happens with psychedelics make you see God?]

While evidence for ketamine’s antidepressant effects is strong, questions remain about exactly how it should be administered, to whom, and how often. And only in the past few years have researchers begun to test it in Field Trip–like regimens—taken in trip-inducing portions in conjunction with talk therapy. If the outcomes are positive, that would align with similar findings for other psychedelic substances.

In my own search for healing, I have tried antidepressants, anti-anxiety meds, and cognitive behavioral therapy. The existing data told me that ketamine might help and, even if it didn’t, was unlikely to do any harm if my practitioners are careful and trustworthy. I decided to take the risk.

IN 2006, WHEN I WAS 14, an episode of House M.D. gave me a glimpse into ketamine’s potential. It’s good TV: After a gunshot wound, the medical drama’s titular drug addict and diagnostic supersleuth emerges from surgery to a confusing series of hallucinations and stretches of lost time. He blames his colleagues for dosing him with ketamine as an anesthetic. They counter there’s research suggesting that a single infusion could alleviate his chronic leg pain. Plot twist! It’s all been a dream, and he’s still bleeding out from his bullet wound. As he’s rolled into the ER, House gasps, “Give me ketamine.”

Later episodes portray a man reborn without pain or strife, albeit temporarily. I remember being amused at the suggestion that just one IV drip might rewire your brain for the better. But when writers scripted the show, real-world research on ketamine had implications beyond easing nerve pain. That same year, scientists at the National Institutes of Mental Health released the results of a trial in which 17 patients with depression received IVs of ketamine while 14 with a similar profile got saline drips. Nearly 75 percent of those receiving the drug showed marked improvement in their depression symptoms the day after; more than a third of them still felt the effects a week later. A quick infusion seemed to accomplish what years of therapy and traditional medication had not.

Meanwhile, the notion that tripping can be a lasting cure for mental illness has been around since the 1950s. Early tests combining LSD, mescaline, or psilocybin with talk therapy delivered promising results. But the Nixonian war on drugs made the substances illegal in 1970, stymying progress for those psychedelics and eventually MDMA as well. Decades of lobbying from academics and the nonprofit research group Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) eventually led the Food and Drug Administration to recommend in the early 1990s that studying MDMA could continue under strict oversight.

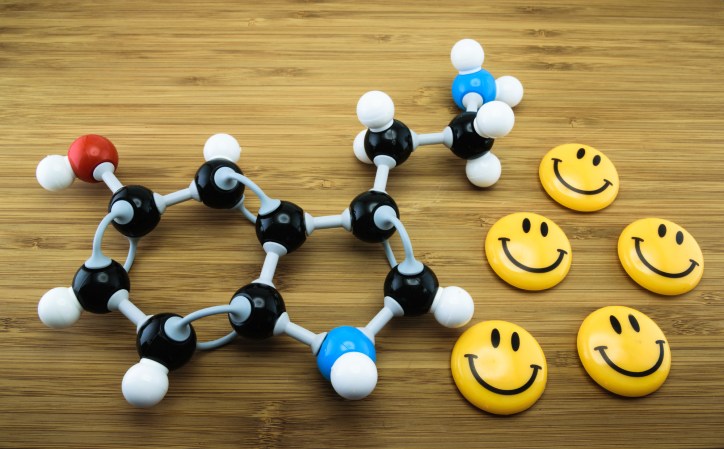

That, coincidentally, is about the same time ketamine came into the conversation, as neuroscientists began to suspect it might affect depression. While all mental illnesses have complex causes, we know that the balance of certain chemicals called neurotransmitters—which facilitate communication between nerve cells—plays a part in regulating symptoms of depression. Common medications such as Prozac and Lexapro primarily act by boosting happy-making serotonin to spur the brain to increase its interconnectivity over the course of weeks or months. Though the exact mechanism by which these drugs work is still rather murky, eventually, researchers at Yale became intrigued by the potential role of another, more abundant brain chemical: glutamate.

If drugs that target serotonin help, they posit, then compounds that zero in on glutamate might help even more. They theorize that depressive symptoms arise when receptors in the brain that handle glutamate—what Gerard Sanacora, director of the Yale Depression Research Program, describes as the “gasoline” of the brain—aren’t being stimulated and can’t do their thing. That causes some synapses, the junctions between neurons, to wither. Ketamine reactivates those glutamate receptors, which may then create a sudden boom of new brain cell connections as the system goes back to normal. They suspect that this superbloom of neural networks represents a quicker, more reliable version of the same process by which more mainstream antidepressant meds work.

It seems far-fetched that something as complex as trauma, which can come from any number of sources, could disappear with a single shot.

While the precise mechanism at play remains unknown, when ketamine is effective, it can be like flipping a switch. “In psychiatry, we just generally don’t have treatments that work quickly,” says David Feifel, who was a professor of psychiatry at UC San Diego when he read the 2006 NIMH ketamine study. “I thought, If this is even half as good as it appears to be, it’s going to be a blockbuster.” Consider the potential impact: More than 264 million people on Earth are affected by depression, according to the World Health Organization, which makes it a leading cause of disability and a major contributor to suicide, which kills nearly 800,000 people globally each year. Knowing the stakes, Feifel set out to look into ketamine for himself.

With the drug readily available as an anesthetic, he opened an outpatient program at UCSD in 2008 and began collecting data, though he recalls that some of his colleagues acted as if he were the one in need of psychiatric help for starting the practice. “It was very controversial,” he says, but the effort maintained the university’s approval by treating only the most desperate. “We started with the patients who had tried everything and failed and were suicidal if we didn’t do anything,” Feifel says.

In 2014, psychiatrists and neuroscientists at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai published the first randomized trial on ketamine for chronic PTSD in JAMA Psychiatry. They had found a marked reduction in symptoms in their 41 subjects after a single dose. Three years later, Feifel published his own findings in the Journal of Affective Disorders—the first report on how ketamine patients fared outside the controlled setting of a clinical trial, and one that confirmed the drug’s efficacy in treating depression. Since then, a handful of other small studies have supported Mount Sinai’s results, and some suggest that repeat dosing may help sustain improvements in mental health over time.

Convinced that academia was moving too slowly, Feifel opened a private clinic offering ketamine and other therapies in La Jolla, California, in 2017. While he agrees that more work is needed to fully harness the drug’s potential for depression and other conditions, he has no qualms about carefully monitored use in private facilities. “There’s too much suffering out there,” Feifel says. “We’ve got to help people, because their lives are ticking away.”

FIELD TRIP’S PRACTITIONERS ease me into higher doses with each visit, and it’s around the halfway point in my regimen that I go from feeling slightly not-lucid to knowing what it means to be high on ketamine. My “journeys” are at first unfamiliar but easily described: a feeling of deep contentment, of being held close, with rapid-fire thoughts that seem somehow more profound than they would otherwise, and perhaps a slight sense of disconnection from my body. By the fourth session, the experiences become almost impossible to articulate.

Under the influence of 85, 90, 100 milligrams of ketamine (Field Trip set my max dose at around 1 milligram per kilogram of body weight), my perception of time and sound warp in irreproducible ways. I see colorful patterns. Not swirly like clichéd lava lamps and black-light posters, but tessellated or jagged like pyrite. The shapes collapse in on themselves and cycle in time with the music from my headphones, which also collapses in on itself and becomes quite atonal. I frequently feel as if I’m sinking into heaps of soft grass. The world and everything in it is made of shades of green.

Somewhere in this emerald whirlpool that looks like pixelated glass but feels like a cloud, I hope to find and slay my demons.

Living with PTSD has been like living in a haunted house. It’s not inherently untenable. I’ve met ghosts capable of tormenting me for a few hours or days, but most are benign. Still, I never know when a bubble bath will remind me of the nights I spent floating in my ex’s tub feeling as if I might as well die. I lose time and expend a lot of emotional energy occasionally ruminating on my past self’s inability to leave an abusive relationship. Sometimes it feels as if jump-scare-loving ghouls have settled into my sock drawer and under my desk, and I have no way of knowing when they’ll choose to pop out.

Then there’s the existential threat. To live with PTSD, for me, is to know that there is always the possibility that I will be scared to death. That a memory will emerge that I cannot recover from. That I will become mired in helplessness and despair in a way that nothing—not the happy marriage and comfortable home of my current life nor the years of therapy I’ve absorbed—will be able to counteract.

Unfortunately for me and upward of 8 percent of the US population, PTSD is even less understood than major depressive disorder, though the two often tend to darken the same halls. Early research like the 2014 Mount Sinai study suggests that the same kind of miraculous plug-and-play IV therapy that makes ketamine a game changer for depression might help PTSD patients, but the effects on both can be temporary. As difficult as it was for psychiatrists 20 years ago to believe that ketamine might turn depression around in a day, it seems even more far-fetched that something as complex as trauma, which can come from any number of sources and manifest in infinite ways—from violent flashbacks to emotional detachment—could disappear with only a single shot.

But the practitioners at Field Trip don’t promise quick fixes. My treatment protocol, informed by the work laid out by the MAPS research group and similar organizations, is far from a fast infusion in a doctor’s office. It begins with a psychiatrist’s evaluation and an hour-long initial session with the licensed therapist who will guide me through the process, which consists of two ketamine experiences a week for three weeks. Before each, I meet with my therapist to set intentions. I talk about my history of eating disorders and my recurring memories of abuse, and how I would like to find some kind of healing. A nurse practitioner takes my vitals as I settle in. Then it’s into the dark, curated streaming playlist void, and I feel the dull punch of the drug being shot into my tricep.

I’m aimless and out of it for about an hour at most. Though I occasionally zero in on some profound realization under the swirling green, it’s in the integration phase—the 20 or so minutes I spend talking with my therapist as I wake up and the hour I spend talking to her over video chat the following day—that the real magic is happening. Feeling soft and open (“expansive” is the word I often write in my journal), I experience a mental quiet I have never known before. I’m able to have one single thought at a time. I luxuriate over each notion like it’s a piece of chocolate melting in my mouth. I am achingly kind to myself in these moments, and I ache to be so kind to myself at all times.

This course of treatment—a high-intensity trip bookended by shrink sessions—is known as psychedelic-assisted therapy. The evidence has piled up that this approach works with other drugs, but no one’s stringently tested it yet with ketamine. A 2020 overview, authored by several experts in association with the American Psychiatric Association Council of Research, concluded that, based on existing clinical trials, MDMA seems to be effective against PTSD when combined with tailored therapy. The same is true for psilocybin as a remedy for depression and cancer-related anxiety. Results are more scant, but promising, for LSD.

[Related: 8 common misconceptions about drugs]

Although ketamine has the most data backing its use in addressing depression out of the whole bunch, it’s gotten the least academic attention in terms of developing treatments that combine it with therapy. “The issue with ketamine now is that it’s already out there,” Feifel says. “It’s approved for anyone to use in any way, which makes it hard to set standards.” Any physician with a controlled-substance license can administer the stuff. That means clinics can make up their own ways of using it—ranging from IVs of the drug administered by anesthesiologists to lower repeated doses. There’s even an FDA-approved ketamine variant, Spravato, which shows great promise in fighting treatment-resistant depression and isn’t intended to induce psychedelic experiences at all. The question for places like Field Trip, Feifel says, is how to determine if therapy provides an added benefit and whether psychedelic experiences are a crucial part of the process. Those answers require more research.

When the FDA clears other psychedelics specifically for treating depression and PTSD, Feifel expects to see more standardization in how they’re used. Advocacy groups like MAPS envision a future where people struggling with their mental health can work with practitioners to decide which mind-altering compound might assist them and how they should combine the experience with therapy to best achieve long-term healing.

BECAUSE OF THE LACK of existing data on ketamine for psychedelic-assisted therapy, there’s no clear endpoint at which I’ll be able to say it’s “worked” for me and that the benefits won’t slip away in time. More than three months after my last treatment, I still feel improved, though perhaps not as radically as I did a few weeks ago. I will keep going to talk therapy. I will keep meditating. If I start having more “bad” days than “good” ones, my therapist might recommend a “booster” appointment a couple of times a year or as often as every six weeks. Maybe I’ll try other drugs too.

In the course of my reporting for this article, more than one researcher told me they would just love to see how I’d do on MDMA, which, if current trials stay on track, could get the FDA greenlight as soon as 2023. Field Trip, for its part, is working on developing more long-term solutions that don’t necessarily require more drugs; the company plans to create group counseling options for people who’ve been through the experience. Regardless, I do feel the ketamine sessions helped me. With nothing to compare them to and a sample size of just one Rachel, I can’t draw any broader conclusions.

[Related: Oregon voted to legalize mushrooms. Here’s what that means.]

For me—despite the fact that science can’t yet explain precisely why—having taken ketamine helps me see that I’m not trapped in a haunted house. I am the haunted house.

It’s like this. Somewhere in the midst of my fourth treatment, when I’ve decided to focus on seeking respect for myself and my body, my abuser finally appears. My dose is high enough at this point that thinking of anything, including my own name, leads me to lazily roll the word around in my brain as an abstract concept: What is a “Rachel,” really?

At last, the pathological narcissist who coercively controlled me all those years ago floats through my hazy green space. I immediately grasp that he is physically a part of me. By that I don’t mean I’m mulling over the great oneness of all living things. When I emerge from the trip and enter the integration phase of my treatment, what I write in my journal is not that we are universally connected. I write that the memories and horrors and ruminations that make up my PTSD are not my ex. They are me. I do not have to fight and struggle to excise them, but rather to love and cherish and heal them.

On my way home from my final session, I think I see the man who abused me. My Lyft idles at an intersection where I might once have expected to run into him, and someone in the crosswalk lights up my brain like a parade. His face is turned away, but his clothes, his swagger, the flip of his hair. Could it be? No, as it turns out. The hands are all wrong.

As we coincidentally follow this stranger from stoplight to stoplight, crawling in rush-hour traffic, I ask myself what this soft, enlightened, expansive Rachel would do if it were the man who’d pitted and scarred me inside and out. Would I simply close my eyes and wish him well? Would I lower the window and shout forgiveness?

No, I decide. I would still tell him he could go rot in hell. My sense of connection and empathy didn’t change how I would confront a bad man standing right in front of me. Nor did it quiet the protective instincts that had long left me on edge whenever I passed through his old stomping grounds. But I do feel better able to put the ghosts in my head to bed. I settle back into the folds of my rideshare’s leather seat and close my eyes the rest of the way home.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2021 Calm issue of PopSci. Read more PopSci+ stories.