Scientists studying Titan’s atmosphere have learned it can create complex molecules, including amino acids and nucleotide bases, often called the building blocks of life. They are the first researchers to show it’s possible to create these molecules without water, suggesting Titan could harbor huge quantities of life’s precursors floating in its atmosphere. It’s a breakthrough that even has implications for the beginning of life on Earth.

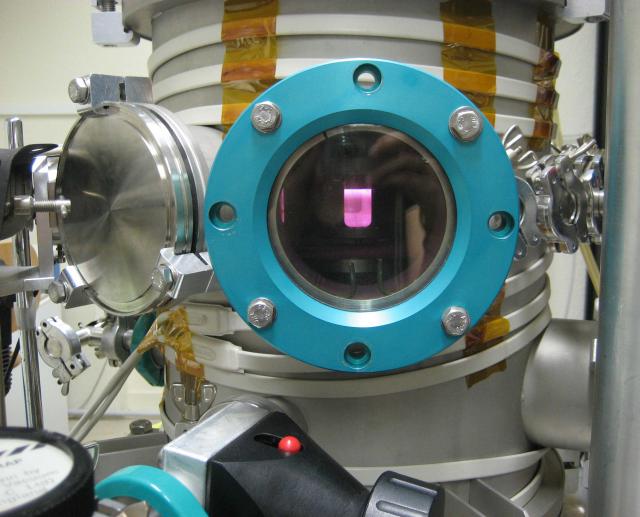

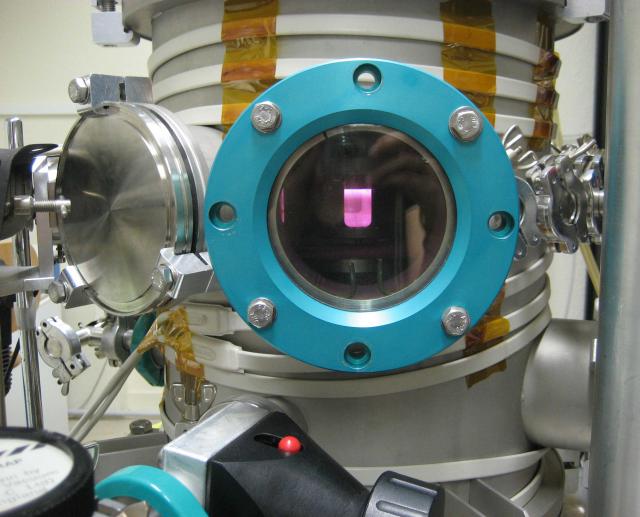

Researchers at the University of Arizona built a simulated Titan atmosphere in a special chamber in Paris and blasted it with microwaves, simulating the effect of solar energy. The reactions produced aerosols, which sank to the bottom of the chamber, where scientists scooped them up for study. What they found was unexpected, to put it mildly: all the nucleotide bases that make up the genetic code of all life on Earth, and more than half of the 22 amino acids that make proteins.

Of course, this doesn’t prove Titan has life — this was a test chamber, not the actual moon’s atmosphere, for one thing — but it’s intriguing, at least.

“Our results show that it is possible to make very complex molecules in the outer parts of an atmosphere,” said Sarah Hörst, a graduate student in the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Lab, in a UA News story. She led the research effort with her adviser, planetary science professor Roger Yelle.

Titan is one of the most promising places for life elsewhere in the solar system. It has huge methane lakes and scientists recently learned that hydrogen is disappearing faster than it should at the surface, suggesting some sort of chemical reaction is consuming it.

The best data about Titan’s characteristics has come from the spacecraft Cassini, which has tasted some of the moon’s outermost atmosphere in a series of flybys since 2004. But Cassini was not designed to dip below 560 miles above the surface, much too far to really get a sense of what the moon’s atmosphere contains.

To truly test its capabilities, researchers would have to recreate the atmosphere in a lab, mixing the gases found on TItan and subjecting them to radiation. The microwaves caused a gas discharge, the same process that makes neon signs glow, which caused some of the nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide to bond together into solid matter. These aerosols were levitated in a special chamber before they got heavy enough to fall down.

The prospect of small floating life forms in the Titanic atmosphere is intriguing enough, but the study also revealed some interesting possibilities about the genesis of life on Earth. Titan’s atmosphere might be chemically similar to that of the early Earth, suggesting that instead of emerging from a primordial soup, the building blocks of life might have rained down from on high.

Hörst said the most interesting aspect of the study was proof that you can make pretty much anything in an atmosphere — a finding with major implications for astrobiology.

“Who knows this kind of chemistry isn’t happening on planets outside our solar system?” she said.