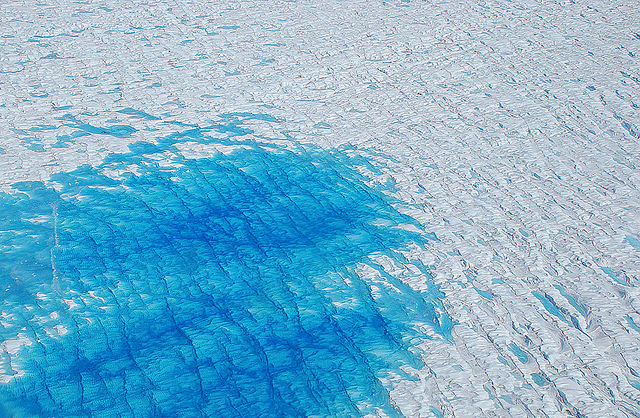

The Arctic, in our popular imagination, is a frozen expanse teetering figuratively and literally on the edges of human culture. It remains primal and wild and unsullied by human contagions.

It’s a nice idea, but one that doesn’t match reality.

The Arctic, as a physical place, is directly connected to the same ecosystems that we humans are polluting closer to home. It’s foolish to think that harming one part of a connected ecosystem doesn’t harm the others, as a study released on Wednesday in the journal Science Advances makes clear. The study found that even in the remote Arctic we can’t escape the megatons of plastic waste humanity unleashes upon the world.

“Most of the surface ice-free waters in the Arctic Polar Circle were slightly polluted with plastic debris,” wrote the study’s authors in the paper, before going on to add, “…plastic debris was abundant and widespread in the Greenland and Barents seas.”

Plastic in the world’s oceans has been a growing concern since at least 1997 when Charles Moore stumbled across the Great Pacific Garbage patch as he crossed the Pacific after competing in the Transpacific Yacht Race. Today we know that there are at least six main garbage patches filled with plastic plaguing the seas. By some estimates as much as 300,000 tons of plastics are in the world’s oceans.

Some of the plastic that ends up there was blown off cargo ships, and others wind up in the ocean because of deliberate dumping. But most wind up there because of carelessness. Many plastic bits end up in the water because of less-than-careful handling of our garbage. Many more enter the oceans because as we deliberately designed plastic products, like microbeads, we never paused to wonder where a piece of plastic designed to be used while you shower ends up when it goes down the drain.

The researchers, a global crew hailing from 8 countries and 12 universities including the University of Cádiz in Spain, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia, and Harvard University, came to this conclusion by literally dragging nets across the arctic and looking to see how much plastic they picked up. They sampled a total of 42 sites across the Greenland, Barents, Kara, Lapteve, East Siberian, Chuckchi and Beaufort seas along with the Canadian Archipelago, Baffin Bay, and the Labrador Sea.

To make sure they were capturing as much as the plastic as possible, they used a stereo microscope to aid in their search, enabling them to catch pieces of plastic as small as 330 micrometers—about four times thicker than your typical strand of human hair. They then analyzed and classified them according to shape and probably point of origin.

Plastic in the ocean isn’t just unsightly. In fact, the plastic debris that we see is less of a problem than the plastic that is too small to see easily. That’s because plastic never biodegrades. It doesn’t revert back to its molecular elements the way other materials do.

Given enough time a leaf laying on the soil floor will be eaten by bugs and microbes to become soil that once again provides the tree with nourishment. Given enough time plastic will become a smaller piece of plastic. That’s it – this stuff never goes away. Eventually, after being buffeted about by sun and salt water, it becomes small enough that sea animals confuse it with morsels of food such as seaweed, or plankton. A 2015 study found that roughly 20 percent of small fish have plastic in their bellies. Researchers have also found that some northern fulmar’s, a sea bird that hangs out mostly in the subarctic, have elevated levels of ingested plastic. Plastic it seems, is not just an occasional snack, but a steady part of their diets. Tasty.

Not only is plastic not food, but it is associated with a cocktail of potentially harmful chemicals. Some plastics are made of chemicals which cause cancers, or that disrupt hormonal systems associated with sexual reproduction and general wellbeing. Plastic in the oceans can also act as a magnet for other chemicals – dioxins, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)—which also cause cancer and interact with hormones that we also dump in the ocean. Biologists are still trying to figure out what this means in terms of the health and wellbeing of the fish, and the humans who eat these fish.

Not many people live in the Arctic, certainly not enough to account for the level of pollution they found. Researchers in this study were able to trace back the plastic, not surprisingly, to the North Atlantic—to the more heavily populated coasts of Northwest Europe, the United Kingdom and the east coast of the United States. Ocean currents—driven by changes in temperature and salinity—ordinarily send warmer waters up to the cold reaches of the Arctic. Now, they also pick up plastic hitchhikers along the way.

Given what we know about human activities and ocean currents, it’s not shocking that researchers found plastic in the Arctic. What is disconcerting is that after decades of research in the area people still think of the Arctic as pristine. We already know that Arctic whales have PCB’s, polar bears have long been contaminated by DDT, and even animals in the deepest parts of the oceans are being poisoned by toxic chemicals. What’s surprising is not that this is happening, but that this continues to happen and that we continue to be surprised.