What lurks in the deepest depths of the sea? PCBs (Polychlorinated biphenyls), and PBDEs (Polybrominated diphenyl ethers) according to a study released Monday in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

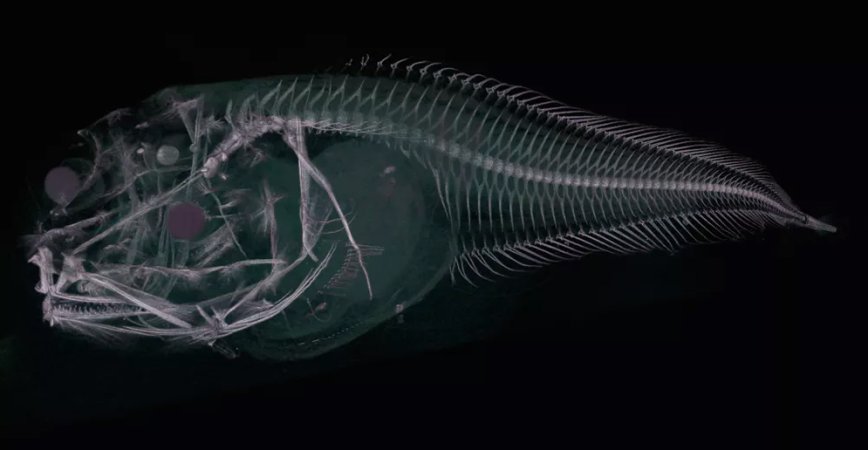

Researchers analyzed the chemical loads in amphipods, a kind of crustacean related to sandhoppers. But unlike beach-bouncing sandhoppers, the scientists collected their critters from the deepest parts of the ocean—the Mariana Trench in the North Pacific and the Kermadec in the South Pacific. They pulled the amphipods from depths between 4.5 and 6.5 miles below the surface. Around 45 percent of the ocean is Deep Ocean, but we don’t know much about it.

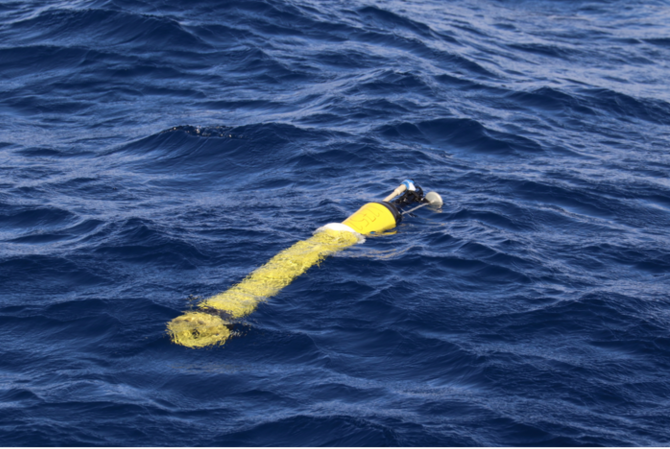

“Going beyond 6000 meters [3.7miles] is difficult in terms of equipment,” study author Alan Jamieson, an ecologist at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom, told PopSci. “No manufacturer makes products that will go that deep, so you have to make your own. My group has a special mix of engineers and biologists so that we can go to these depths.”

Despite their distance from the surface—and all of humanity—all of the samples tested positive for PCBs and PDBEs. They’re classes of chemicals so toxic that an international treaty restricts their use. The United States banned the use of PCBs in 1979, but they still persist in some products, especially vintage electronics, and in the environment.

The chemicals are dangerous because they harm human and animal health, don’t break down in the environment, and tend to disperse. PCBs, for example, were first discovered in the late 1880s. Researchers have found PCBs in the bodies of polar bears in the remote Arctic Circle and in the bodies of Antarctic fur seal pups. Researchers have even detected PCBs in museum samples of birds dating back to 1914, about a decade before companies began to use the chemicals widely. Your body almost certainly has PCBs in it right now. Given their ubiquity, it wasn’t all that surprising that the amphipods had PCBs and PDBEs in their tiny bodies.

“But one big surprise was how unbelievably high they were,” said Jamieson. The levels of PCBs were higher than in amphipods tested at known sites of contamination—extremely polluted rivers in China, for example. “You think we’re at the Mount Everest of the ocean, the very deepest point, and the levels were coming out orders of magnitude higher than places you would expect for it to be really high,” he said.

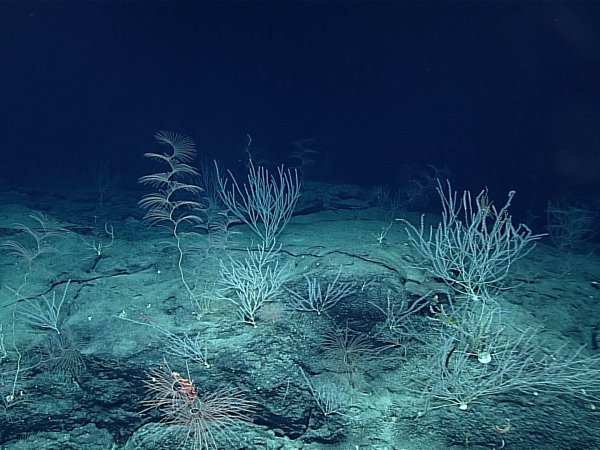

Jamieson thinks that amphipods are cursed by their scavenging lifestyle. They live on decomposing animals and plants that filter down from above. When a whale dies, for example, its body sinks slowly to the ocean floor. At least part of its body becomes dinner for the amphipods.

“The deep ocean floor acts like a bin that things fall into that can’t get out,” said Jamieson.

A whale’s body is likely to be polluted due to bioaccumulation. It eats tons of fish, shrimp, larvae, plankton, crabs, krill, fish, and so on, and each tasy morsel likely has some PCBs and PDBE in its body. The more a whale eats, the more PCBs and PDBEs build up in its body. And because PCBs are fat-soluble, blubbery whales have even more room for storing these chemicals than most creatures do. By the time the time a whale dies and an amphipod eats it, that cetacean has become a veritable PCB buffet.

This exposure isn’t harmless. Humans exposed to PCBs can suffer from liver and skin damage. In children, exposure can cause a host of sexual, skeletal, and neurological development issues. In birds, PCB exposure causes brain changes that alter their songs. In shallow water amphipods, PCB exposure is known to harm reproduction.

“We can only assume that it does the same [in deep sea amphipods],” said Jameson. “The problem with deep water amphipods is that we can never study them alive. They live in such high pressure that if we bring them to the surface they die.”

Katherine Dafforn, a marine ecologist at the University of New South Wales, noted in an accompanying commentary that “there is increasing evidence that the unique marine creatures in these trenches are threatened by human-made pollution.” It’s an ecosystem that we know very little about, so these troubling findings are likely just beginning to scratch the surface.

“Shallow water marine biology has the luxury of 200 years of work to underpin your science on,” said Jamieson. “In the deep sea we can just go, well, everything’s contaminated. What was it like in 1929? We don’t know. We didn’t even know if the trenches were there in 1929.”

You might take comfort in the assumption that this is a problem that can only improve. Surely nobody’s dumping PCBs and PDBEs into the environment anymore. We’ve learned our lesson, right? Don’t get your hopes up.

“In the last 12 months, there’ve been countless stories of microbeads in cosmetics and toiletries being flushed down people’s bathrooms, out to sewage works and out to the sea,” said Jamieson. “Nobody thought that if you put millions of little plastic particles into toiletries that are designed to be washed down the drain that they might end up in the sea. Of course they do—where else are they going to end up? So there was no lesson learned. Here we are 30, 40 years later and we’ve just done the same thing with a slightly bigger particle.”

Microbeads actually attract PCBs, which get stuck to their tiny surfaces. And when they float in the ocean, they look an awful lot like fish food.