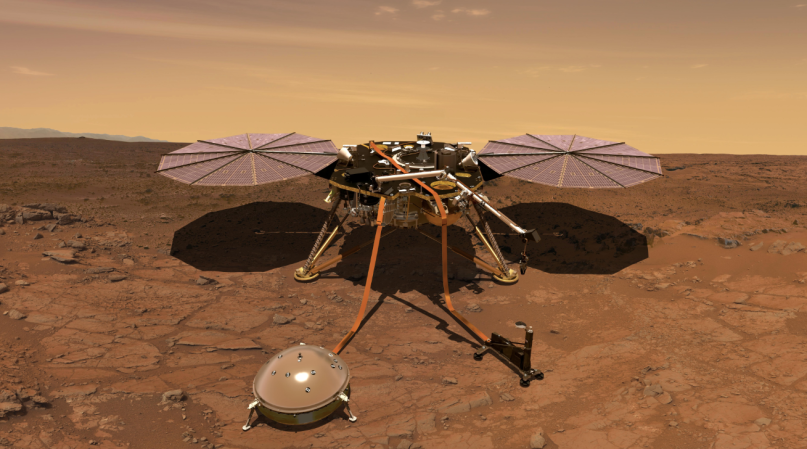

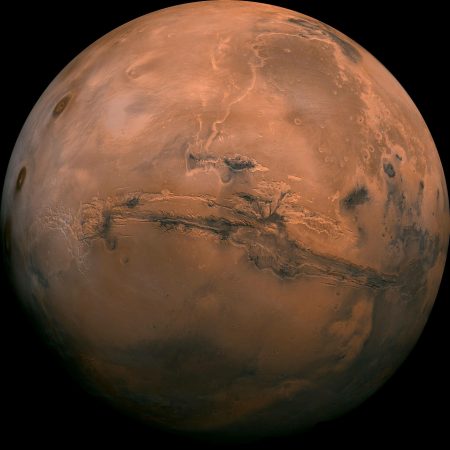

Last week a gust of wind swept across the Elysium Planitia, the tropical plane that straddles the Martian equator. It spun off small eddies and rattled rocks, as Martian winds often do, but it also shook NASA’s InSight lander—a very recent arrival on the Red Planet.

InSight was listening as the gust passed by, picking up its side effects with two sensors. The seismometer, currently onboard but soon to be moved to the ground nearby, picked up vibrations from the solar panels that border just on the lower edge of what a human can hear—provided your headphones have good bass. An air pressure sensor also captured vibrations in the air directly, which more closely correspond with our notion of sound. On Friday, NASA released an interplanetary mixtape featuring the original recording, as well as remixes better attuned to the human ear.

Here’s the tracklist:

- Seismometer original recording (0:36 – 0:55)

- Seismometer recording moved up two octaves (0:55 – 1:10)

- Air pressure sensor recording compressed one hundred times (1:10 – 1:39)

“What you’re hearing,” says Don Banfield, a researcher at Cornell University who worked on the air pressure sensor, “is just the wind noise blowing on all of the things in our vicinity.”

If the recording strikes you as otherworldly, that’s because it is. Air on Mars is completely alien to the air that we know from Earth, and its behavior is appropriately bizarre.

Most notably, the pitch of the wind is far too low to hear, despite blowing at an estimated 10 to 15 miles per hour. To make the sound audible, Banfield says his team had to run the tape one hundred times faster—meaning that the final 29 seconds was recorded in real time over the course of 48 minutes on Mars.

Wind is constantly kicking off small eddies when it encounters objects, just as currents in a river do when they meet rocks and logs. Those eddies spin off even smaller vortices, which repeat the process until there isn’t enough energy left to sustain anything smaller. How high or low the wind sounds to us depends on the size of the swirls that reach our ears.

While eddies on Earth can get down far below a millimeter in size, on Mars the process tends to peter out at around a centimeter, Banfield says. Since the Martian atmosphere is one hundred times thinner than Earth’s, it can’t carry nearly enough energy to reach the smaller scales. As a result, you get ultra-low, rumbly wind.

But that’s not to say all Martian breezes would be impossible to hear. Banfield estimates that an astronaut would certainly notice any gusts hitting about 30 miles per hour. “I think it would be like a low hum as opposed to the high frequency ‘chhhh’ white noise that we hear on a windy day,” he says.

You’d also have a hard time talking on Mars, he says. Putting aside the health hazards of taking off your space helmet, Martian air just doesn’t carry the human voice as well as terrestrial air does. While our atmosphere is made up mostly of nitrogen, air on Mars is almost entirely carbon dioxide. The size and shape of the CO2 molecule make it prone to spinning when hit by vibrations of the type human vocal cords produce, and that rotation leeches energy from sound waves, making them die out quickly. On the bright side, one thing future outposts won’t have to worry about will be noise complaints.

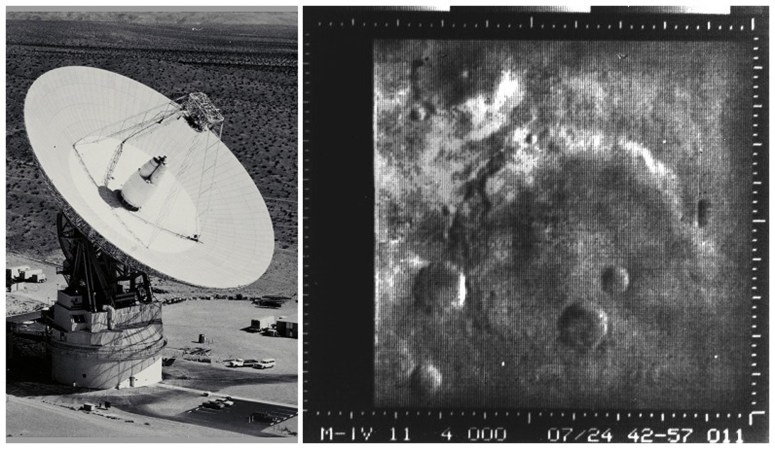

Targetting the sounds of Mars first caught the imagination of astronomer Carl Sagan, who suggested NASA pursue such a recording in 1996. “Even if only a few minutes of Martian sounds are recorded from this first experiment,” Sagan wrote in a letter, “the public interest will be high and the opportunity for scientific exploration real.”

NASA worked with The Planetary Society, which Sagan helped found, to add a simple microphone to the Mars Polar Lander. But the device was lost along with the spacecraft when it crashed into the surface in 1999.

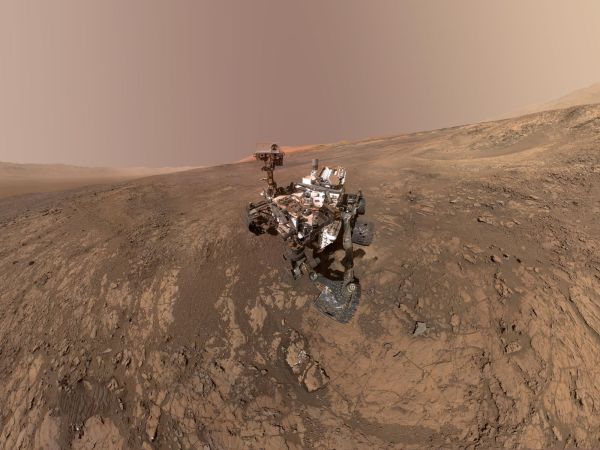

Banfield says his team hopes to hear other noise sources besides wind over the next two years, such as exploding meteors. Two traditional microphones will also accompany the upcoming Mars 2020 rover to the Red Planet, keeping Sagan’s dream alive and well.