On Monday, citing a congressional mandate and reports of drones near airplanes, the FAA announced that any unmanned flying vehicle heavier than half a pound would have to be registered with the government by February 19th, 2016. This is a huge change for the hobby, and one the FAA says it’s implementing out of an overriding concern with safety. There’s just one catch: if the FAA really wanted to protect planes from small, autonomous, unmanned objects — they’d ban turtles first.

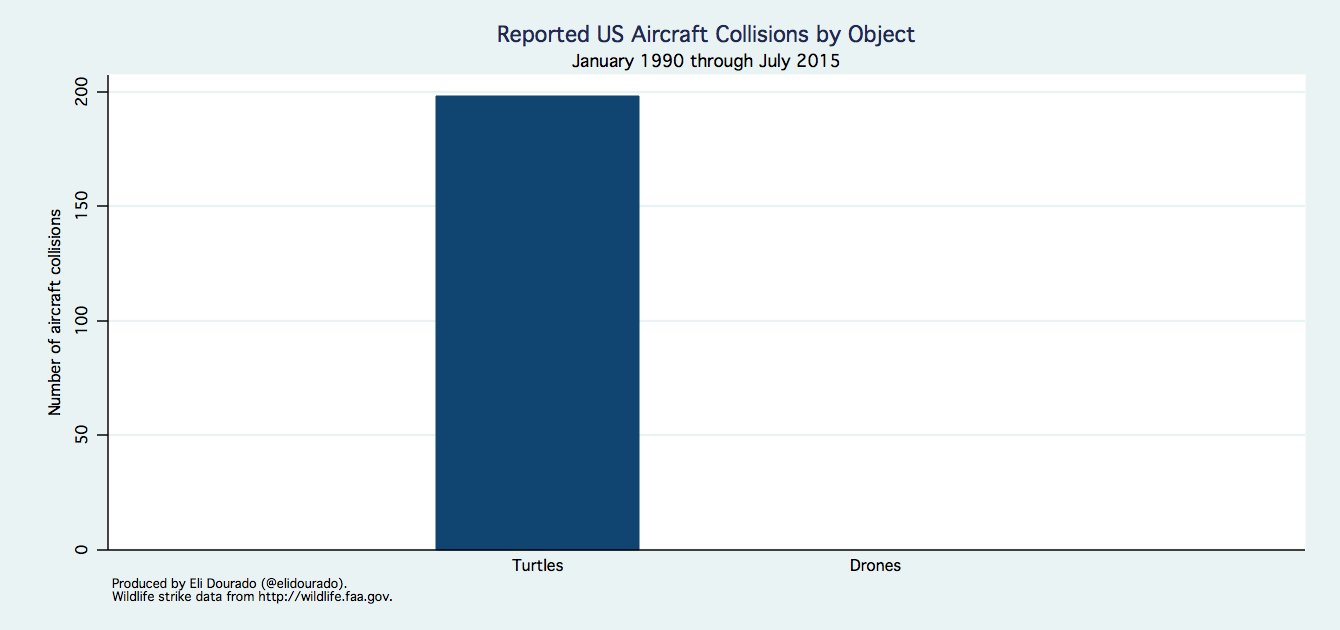

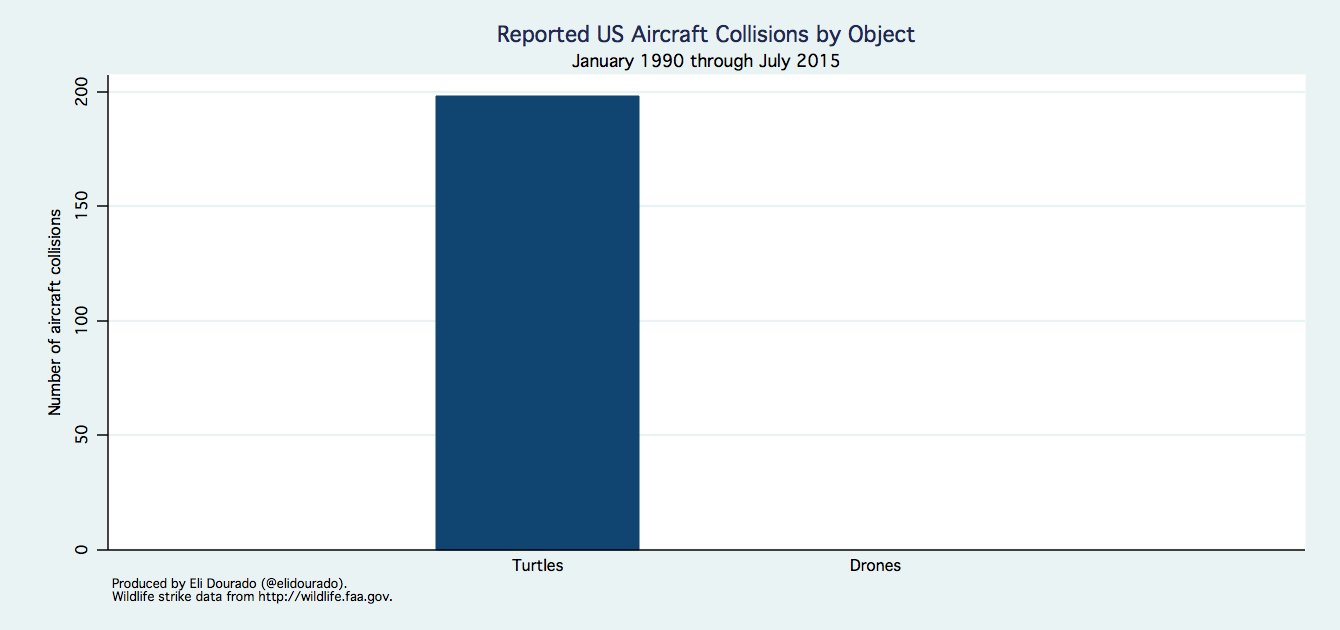

At least, that’s the argument of Eli Dourado, an economist and technologist at the libertarian Mercatus Center. Using data pulled from the FAA’s own database of wildlife strikes, he created the chart above and posted it on Twitter earlier today. Since 1990, the FAA recorded 198 airplane-and-turtle collisions, and exactly zero drone-and-airplane collisions. Even when the FAA warned about an increase in drone and airplane “encounters” earlier this year, the encounters were limited to drone sightings, not actual collisions.

“To investigate the risk that small drones pose to the airspace,” Dourado said over email, “my collaborator Sam Hammond and I downloaded the full dataset to run some analysis on it. We found not only reports of bird strikes, but strikes of all kinds of mammals and reptiles as well. We thought this evidence was very revealing—planes hit objects all the time. Meanwhile, there still have been no confirmed collisions with drones in the United States.

So why turtles? “I picked turtles because turtles are funny,” Dourado said, “You don’t think of turtles as posing much of a threat to planes, and they don’t. If we’ve hit turtles 198 times and drones 0 times, then maybe we are worrying too much about collisions with drones.”

Earlier studies have shown that drones under three pounds show no more risk to airplanes than small birds, especially if flown below 400 feet and more than 5 miles away from airports, as the law already requires. Registering drones smaller than that means flying toys are now more controlled than ducks, but no deadlier.

This fits into a larger portrait of how bad people are at assessing risk, whether that of plane crashes, cyberterrorist attacks, or even the liklihood of rain. Drones are new and easy to fear, while turtles are ancient and an accepted part of life. If a turtle on a runway isn’t that scary, maybe a drone flown five miles away from an airport shouldn’t be, either