What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits iTunes, Anchor, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show.

Fact: New Zealand was once chock-full of oddities, including a 12-foot-tall bird

By Eleanor Cummins

I love New Zealand (or the idea of it, anyway—I have yet to go). Lorde is my favorite musician. The Breaker-Upperers and What We Do In the Shadows are two of my favorite movies. I’ve spent a year perfecting my impression of a Kiwi accent. And then there is the wildlife.

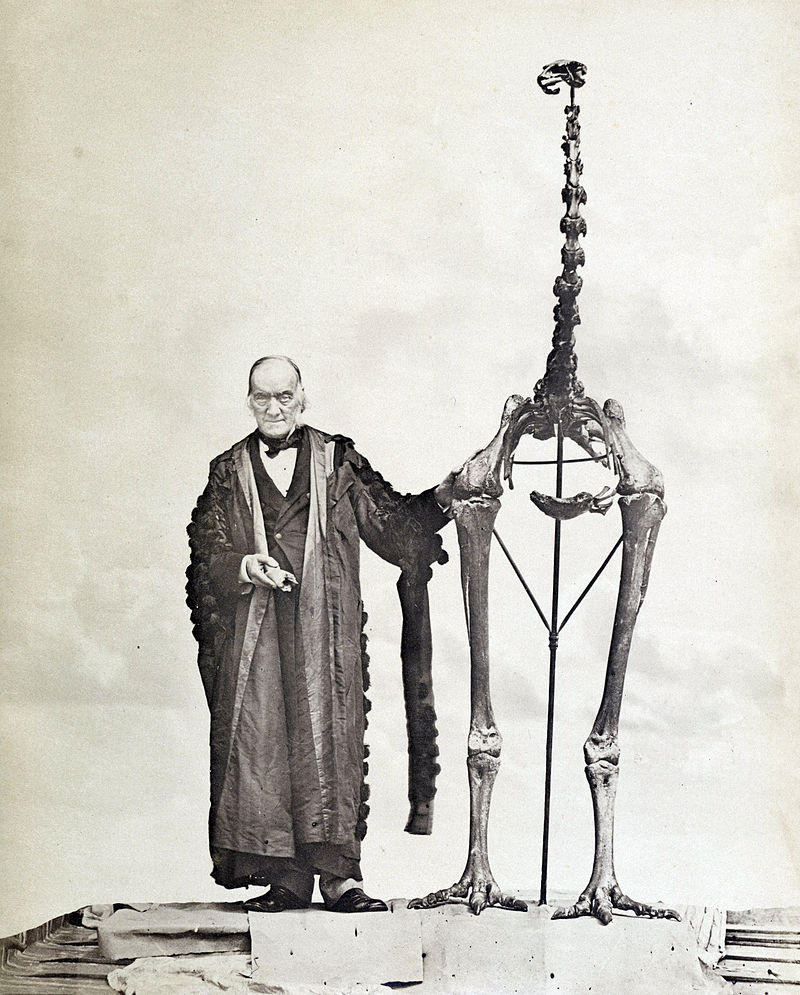

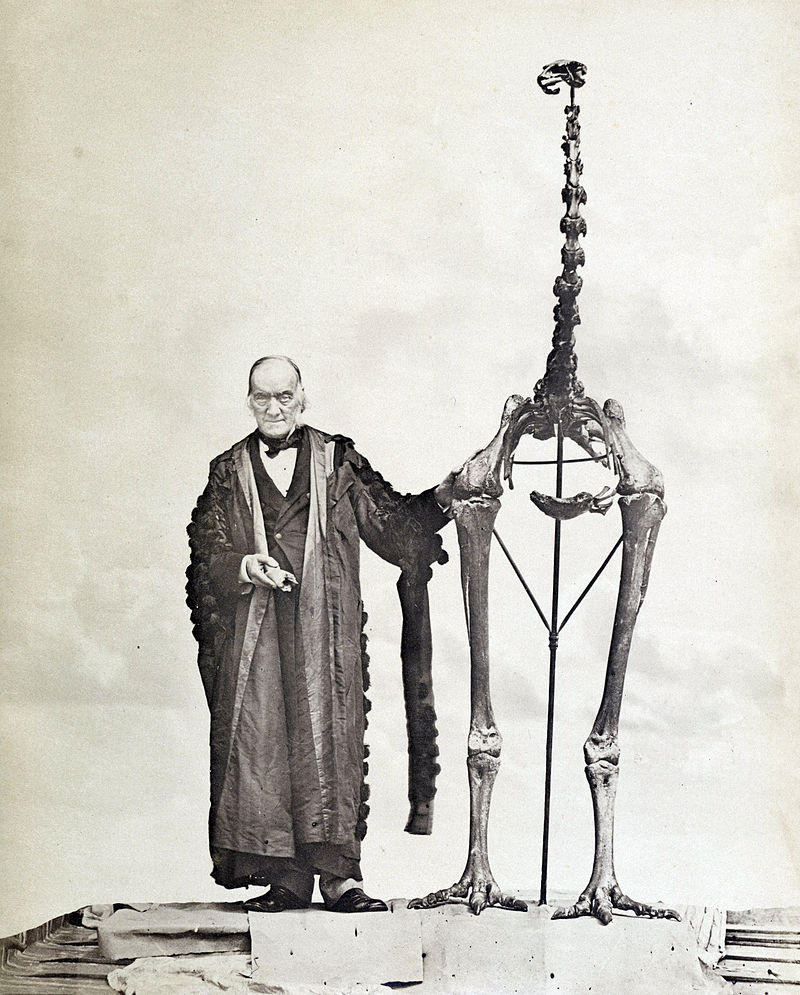

It’s often said that “birds occupied every niche” in New Zealand, which means that eagles were apex predators instead of lions, 12-foot-tall birds called moa were grazers instead of deer, and kiwis served as grub-eaters in lieu of badgers. Some of the creatures mentioned are exceedingly large—according to a principle called island gigantism—and others atypically small—due to the inverse phenomenon of insular dwarfism. Every avian was truly majestic.

The trouble is, the moa and many other unusual species went extinct 600 years ago, and the island nation’s existing animal species are still threatened. According to the World Wildlife Foundation, some 4,000 native New Zealand species are at risk today.

Fact: There’s at least one deer out there that’s eaten human flesh

By Rachel Feltman

We talk about dead bodies a lot on Weirdest Thing. We’ve covered the ins and outs of what happens to bodies once they’re donated to science (spoiler: sometimes they end up in post-mortem yoga studios). We’ve talked about art made out of dead babies, art made out of tattooed skin, and art made out of human skulls (for sale on Instagram, no less). We’ve talked about the plot to turn George Washington into a zombie. We’ve covered the process of mummifying yourself to death and the process of letting mushrooms eat your moldering flesh. We’ve talked about taxidermied people. We’ve even talked about a condition that makes you believe you’re already dead. These are just the examples I can remember.

Anyway, on this week’s episode I take us to a body farm—a facility where scientists watch donated corpses decompose to help improve forensics—and share one of our most delightful body horror stories to date. It’s true: scientists caught a deer munching on human remains. Fortunately (and despite the existence of a condition often referred to as ‘zombie deer’ disease) there’s no risk of Bambi turning into a flesh-hungry predator; the skittish critters probably just snack on skeletons as the opportunity arises, as a sort of supplement to their herbivorous diet.

(As promised in the episode, here are other freaky forensic case studies: death by indoor lightning and mysteriously warm corpses.)

If you’re interested in donating your body to this kind of research, you can find more information on the website of your closest facility. Here are instructions for the University of Tennesee’s donation program.

Fact: One of the rarest elements in the universe is inside Euro banknotes

By Sara Chodosh

Counterfeit anything is fascinating, but I think there’s something especially wild about counterfeit money. Maybe it’s that we’re so motivated to catch counterfeiters because what we consider “real” money is only real in that a government has decided that this is what money looks like. Currencies are just pieces of paper (or plastic or metal) that we’ve all agreed have a specific value. If you can make such a good fake that 99 percent of people are fooled, you’ve kind-of-sort-of made real money—you can use it to buy things, so it has value. Until someone catches on, at which point it becomes worthless in an instant. And in the end, there’s something kind of silly about the idea that some pieces of paper get to have value and others don’t.

Modern counterfeiters are now often so good that the bills they create are virtually indistinguishable from genuine money. There are only a handful of experts who can differentiate between so-called superdollars and real hundred-dollar bills. That’s impressive in and of itself. Today’s currencies have a plethora of anti-forgery devices built into them, including the one I talk about on the podcast today: incorporating rare elements into the bills. There are lots of fascinating ways to fake money (Frank Abagnale Jr., the man made famous by the movie Catch Me If You Can, wrote a fascinating book about how he managed to deceive so many people into taking his forged bills), but I think this one is the coolest from a scientific perspective. I won’t spoil my segment here, though, so tune into the pod to learn about why rare elements are such an effective way to prevent forgeries.

*If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on iTunes (yes, even if you don’t listen to us on iTunes—it really helps other weirdos find the show). You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in weirdo merchandise from our Threadless shop.