What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s newest podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits iTunes, Soundcloud, Stitcher, PocketCasts, and basically everywhere else you listen to podcasts every Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster.

And if you’re in the NYC area, you can come join us for an extra-weird live show on September 14.

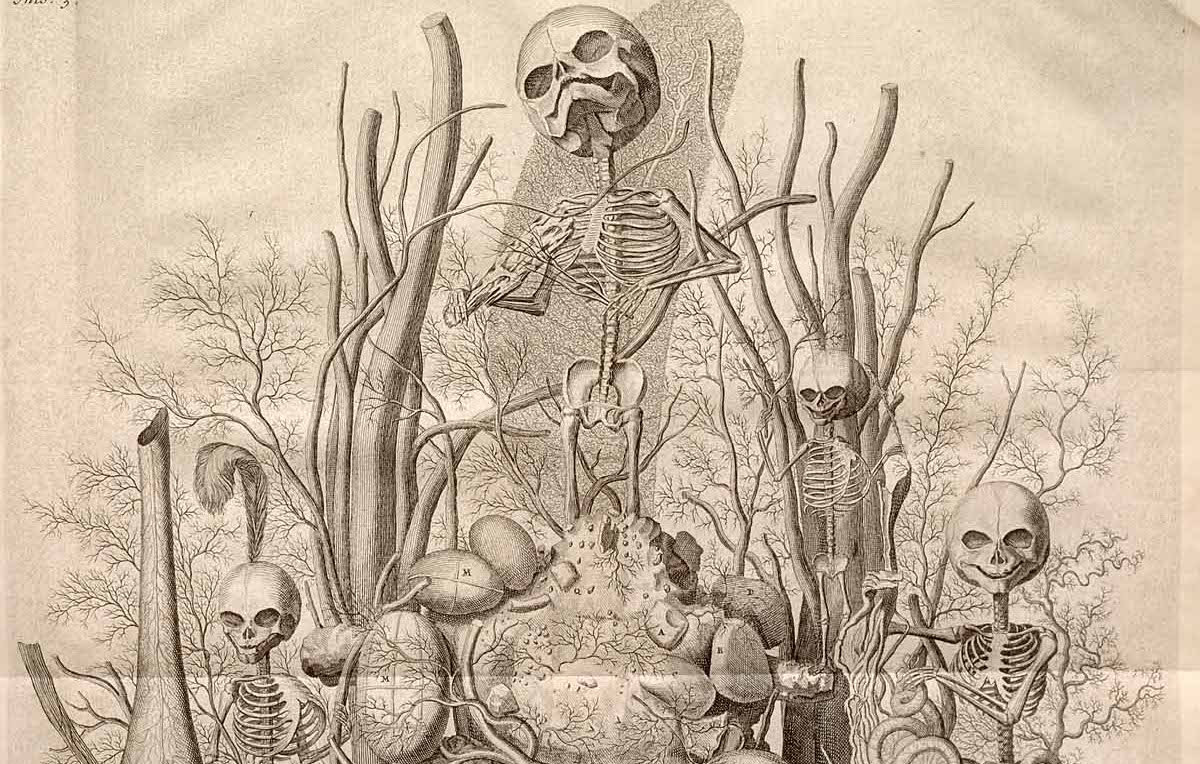

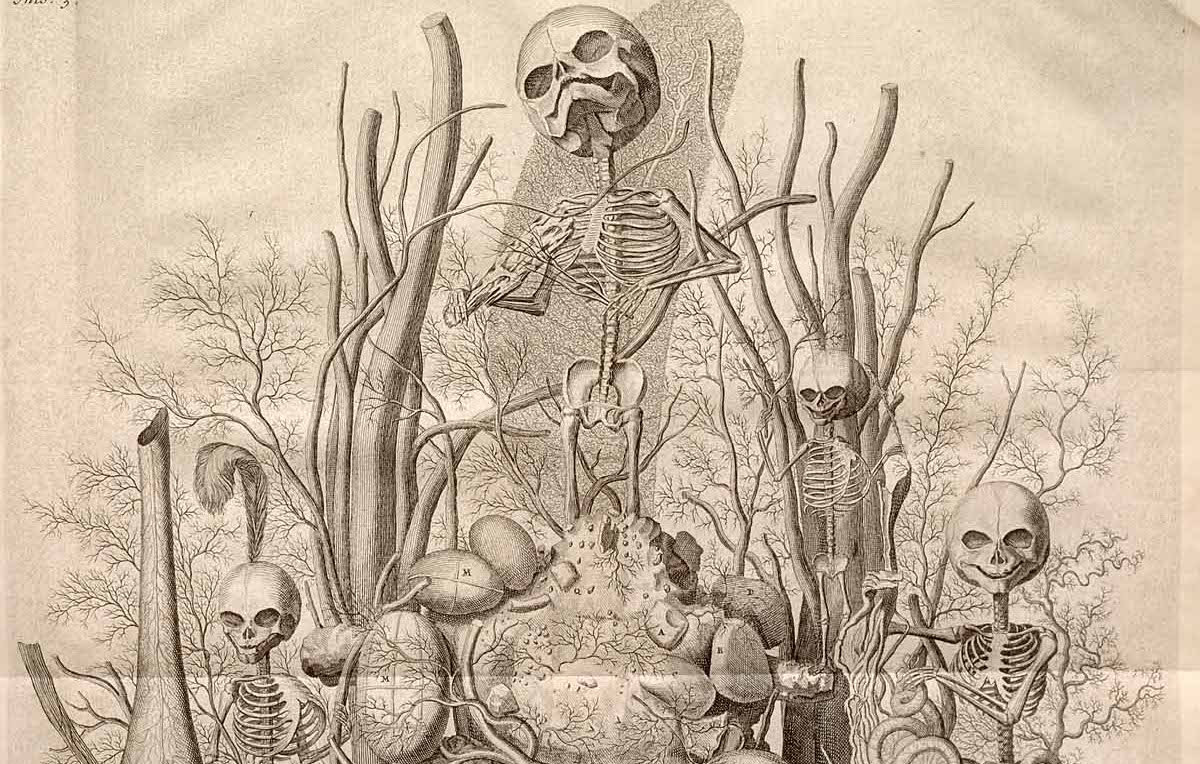

Fact: A Dutch anatomist build artistic scenes using baby skeletons and body parts—and the Russian Tsar loved them

Frederik Ruysch was a Dutch anatomist and botanist fascinated with embalming. As we discussed in this week’s episode, his professional career as a surgeon and obstetrician in Amsterdam gave him access to a lot of bodies, and in his spare time he made huge efforts to embalm humans and other animals in fanciful ways—to preserve their anatomy for future study, and give people a better idea of how the natural world (including humans) worked. Some amazing drawings of his work can be found here.

He injected arteries with a liquid red wax after death. The technique not only gave the bodies a more lifelike appearance but also made it possible for early anatomists to trace tiny blood vessels that would otherwise have gotten lost. He created a museum where he could display his elaborate embalming jars, allowing the public to come in and see his growing collection.

Why pose dead people in weird ways? To keep people interested, Ruysh says: “First of all, I do it to allay the distaste of people who are naturally inclined to be dismayed by the sight of corpses.”

His daughter Rachel helped him with the preparation of the embalming jars while she was young, but she went on to become a widely acclaimed artist, famous for her stunning floral paintings.

The jars become so acclaimed that Peter the Great visited the collection in 1697. In 1717, the Russian Tsar bought the entire collection and moved it back to St. Petersburg’s Kunstkamera museum.

Remarkably, some of his specimens still exist there today, hundreds of years after their creation. Fair warning, some of them are very disturbing, but if you want to take a peek, you can look here.

Fact: The sun once went so berzerk that telegraphs kept running without their batteries

On September 1, 1859, British astronomer Richard Carrington just barely caught sight of a huge solar storm shooting plasma from the sun. The surprise, he said, left him “somewhat flurried.” And he wasn’t the only one shaken up by the incident: the so-called Carrington Event proved to be the most powerful solar storm in at least 500 years. Folks saw aurorae as far south as the tropics, with daylight-bright skies full of red, green, and purple hues rousing them from sleep before dawn. Scientists have studied records from that time in an attempt to determine how severe solar weather affects human health, but haven’t gotten many answers.

We still know surprisingly little about the sun (though there are great advances now being made in the study of solar weather, and the Parker Solar Probe is speeding toward the light to tell us more) but we know that a Carrington-scale event today would cause a lot of technological chaos. The burst of high-energy plasma from the sun would cost millions of dollars in satellite damage alone and leave GPS and possibly electrical grids crippled all over the world. In 1859, however, there were no GPS systems to fail—there was just the telegraph, and it was only about 20 years old.

That’s where we get our coolest Carrington anecdote: there are many reports of telegraph operators getting shocked by overloaded batteries in the wake of the sun’s temper tantrum, and some even caught on fire. A quick fix was to disconnect the battery and shut the system down. But in several cities, operators reported that their telegraph wires kept on transmitting while totally disconnected from any power source. The electrical charge in the air was so great that the machines kept running.

Fact: George Washington may have died because he had too many doctors—but they did consider bringing him back

What killed George Washington? Most say a throat infection, but others say his doctors did—by accident, of course. On a chilly December night in 1799, the former president was indeed suffering from a terrible throat cold. This was probably worsened by his refusal to change out of freezing wet clothes after he got caught in a sleet storm that day (apparently, being on time for dinner was more important than avoiding a chill).

Back in those days, a doctor’s first line of treatment was usually bloodletting, a medical therapy Washington was supposedly very fond of. But when five to seven pints of blood are drained from your body (which is said to be the case after dear George caught cold), you’re not likely to survive. And George Washington didn’t. Most of us are brimming with around 10 pints of blood, although it depends on your weight and height. George Washington was a very large man, but even he wasn’t resilient enough to survive after losing around half his blood supply.

Bloodletting may seem a little counterintuitive these days, but for thousands of years it was a popular medical treatment. Doctors believed illnesses lived in the blood, and so extracting the infectious fluid was the most logical solution. A very dizzy Marie Antoinette received the treatment while she was giving birth—doctors and the queen herself deemed it a success, although apparently at the same time this was happening, someone opened a window to let some fresh air into the room. After having a seizure, Charles II, the king of England in 1685, was also treated by bloodletting. Over the course of three days, he supposedly had almost all of the blood in his body drained. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t make it.

Our poor George Washington met a similar fate, although one of his “best friends on Earth” (that’s according to the friend, anyway) couldn’t accept the tragedy and had a plan to bring George back from the dead. But even the doctors who almost drained the former president dry agreed that wasn’t a very good idea.

If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on iTunes. You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in weirdo merchandise from our Threadless shop. And don’t forget to grab tickets to our live show on September 14. We’d feel weird doing it without you.