What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s hit podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits Apple, Anchor, and everywhere else you listen to podcasts every Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster. If you like the stories in this post, we guarantee you’ll love the show.

Fact: Uranium glass was all the rage

By Eleanor Cummins

This is one of those facts that I can’t stop talking about. I’ve managed to shoehorn it into stories about Iranian nuclear weapons and Game of Thrones dragonglass. But there’s no end to my fascination with uranium glass, which somehow managed to be a household staple for centuries!

As you probably already know, uranium is a naturally radioactive heavy metal that nuclear scientists enrich into atomic weapons and power plants. But starting in the 1830s, with the Austrian manufacturer Reidel, entrepreneurs began using uranium to add new colors to their glass products. Specifically, a color that could generously be called green apple, or maybe just “radioactive glow,” but more honestly is best describe as “urine-ish.”

The style took off, and remained popular for almost 100 years, meaning plates and decorative bowls and cups capable of setting off a Geiger counter could be found in most kitchens. (Fortunately, the radioactivity was pretty negligible.) Even after its big heyday, it eventually evolved into something called “vaseline glass,” which had a milky flair. And the basic principle was reproduced for everyone’s favorite 20th-century ceramic: fiestaware!

For more of this strange history—and some tips on making it rich in the glass collectibles market—listen to the latest episode of Weirdest Thing.

Fact: A Victorian heart medication turned into a gay sex drug

By Rachel Feltman

All props to Alex Schwartz for this week’s facts, which I learned in the course of editing his fantastic Pride Month feature on the history of poppers. You can read it yourself or listen to this week’s show to find out more, but here are a few highlights: Yes, poppers—now a quintessential character in the past and present of gay culture—started out as a heart medicine in the Victorian era. One scientist even brought samples to conferences to let his colleagues take a whiff of the woosh-inducing chemical for themselves. And intriguingly, poppers were briefly blamed by many for the AIDS crisis—even though their use likely lowers risk of HIV transmission.

Fact: Doctors really wanted milk infusions to be a thing

By Marion Renault

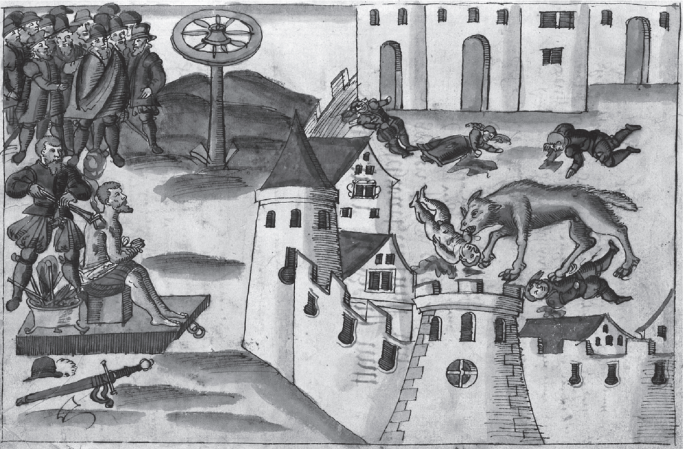

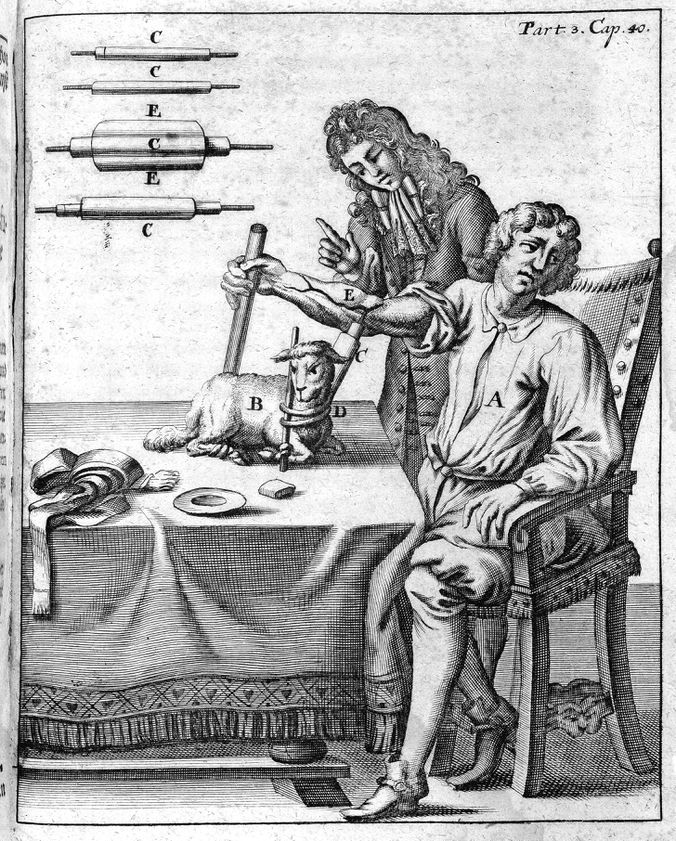

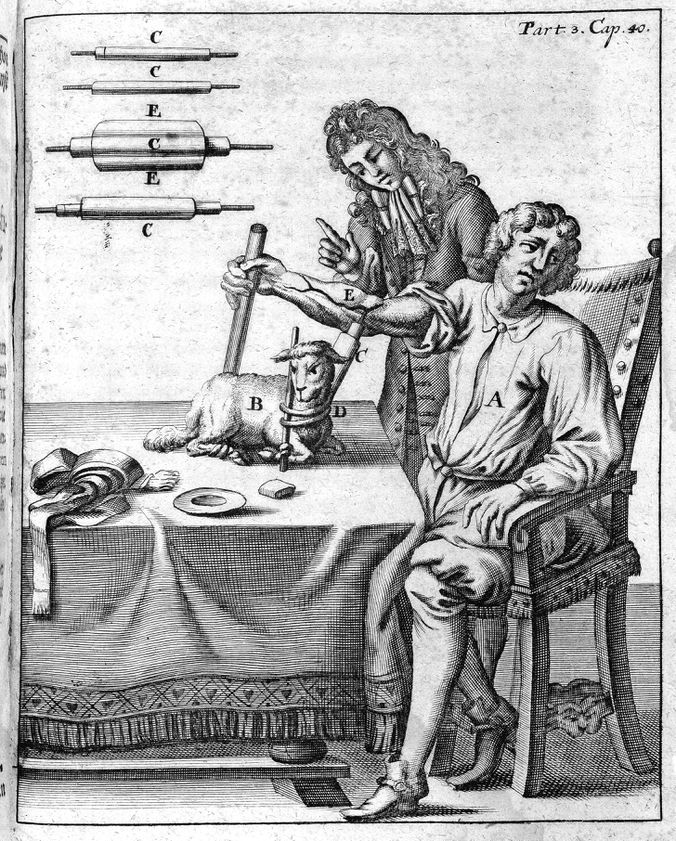

We should be really grateful for the gift of clean, human blood when we receive modern transfusions. In the 1600s (and the centuries that followed), physicians injected animals and humans with everything from milk to urine, beer, sheep’s blood, saline solutions, and perfluorochemicals (a group of polymers similar to Teflon).

In the late 1800s, after about 200 years of messy, often-unsuccessful infusions of human blood—as well as of lamb, sheep, and calf blood—physicians deemed such exchanges undependable (we still didn’t know about blood types or blood-borne diseases or how to keep blood supplies from coagulating). “For a short time, milk seemed to be the panacea,” notes one medical historian.

The first milk transfusions took place in the midst of the 1854 cholera epidemic when a pair of doctors brought a cow into a Toronto hospital and pumped the animal’s milk into their own patients (don’t worry, the milk was passed through gauze and kept in a warm bowl). More doctor followed suit. A Dr. T.G. Thomas transfused milk into a woman suffering from severe uterine hemorrhage. Dr. William Pepper remained optimistic about the procedure even when his patients complained of headache, fever, and renal issues after their bovine infusions. Dr. J.S. Prout suggested a medical-legal use for milk transfusions, proposing they might prolong life to allow “the victim of an assault to identify his assailant.”

Dr. Joseph Howe of New York City was an especially adamant explorer of the procedure. In 1873, he injected 1.5 ounces of goat’s milk into a tuberculosis patient who was soon racked by vertigo, chest pain, and uncontrollable eye movement. Naturally, Howe doubled the dose; the patient promptly died. You can hear more about his egregious experiments on this week’s episode.

Strangely, a century and a half have passed since Dr. Howe’s futile milk experiments and there is still no safe, effective blood substitute approved in the United States or Europe. For now, artificial blood remains a holy grail of trauma medicine. Efforts to synthesize the substance have been—wait for it—in vein.

If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on Apple Podcasts (yes, even if you don’t listen to us on Apple—it really does help other weirdos find the show, because of algorithms and stuff). You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in weirdo merchandise from our Threadless shop.