It’s wasps all the way down. No, scratch that—it’s parasitic wasps all the way down. It’s manipulative parasitic wasps all the way down.

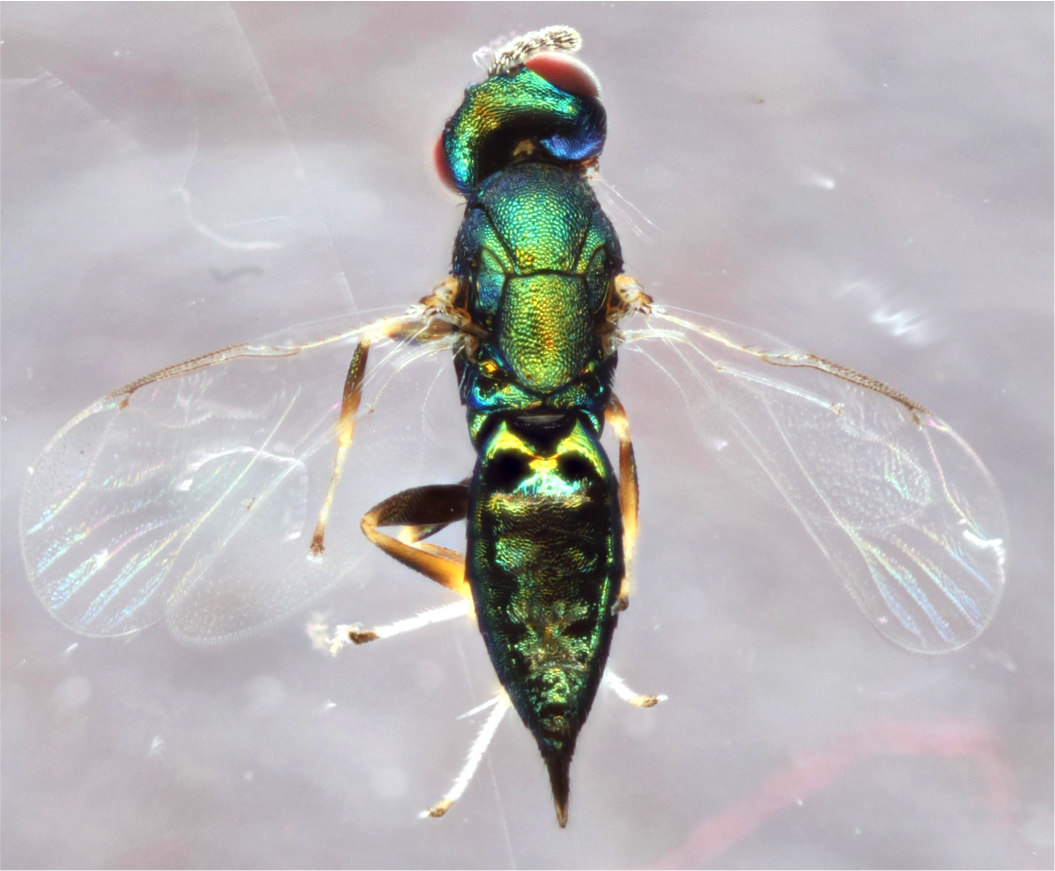

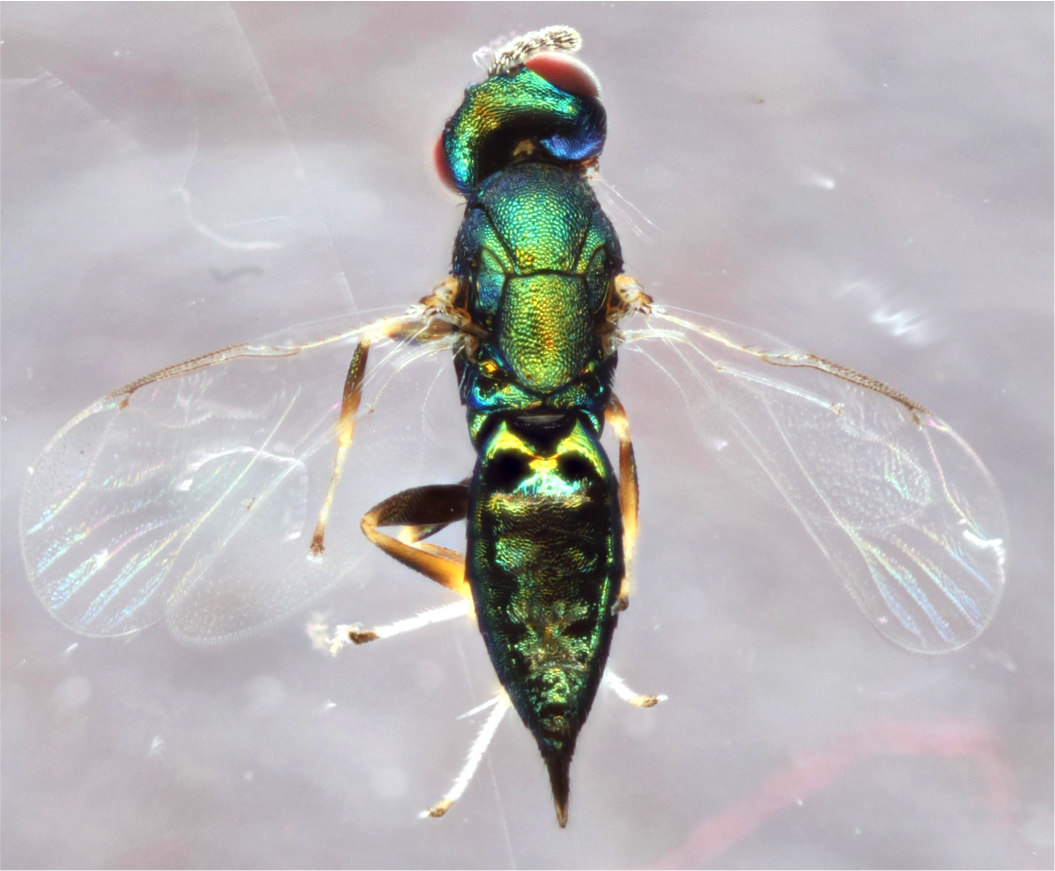

In yet another example of why we should be glad humans have basically escaped the food chain, a group of scientists at Rice University have published two papers describing a new species of wasp that eats its host after using it for personal (or species-wide) gain. The first paper lays out the waspy basics: it lives inside sand live oak branches, it’s part of a large parasitic wasp family, and it lives in southern states (at least as far as scientists know). It was the second paper that documented the creepy lives these wasps live.

Kelly Weinersmith and Scott Egan, two of the leading researchers on this project, first found the hyper-manipulative wasps by studying the slightly-less-manipulative crypt gall wasp. “Crypt” in this case doesn’t mean they live alongside dead human bodies, it means that they form their own crypts—except their crypts help them sustain life.

Larval Bassettia pallida (as the crypt gall wasp is more scientifically known) manipulate sand live oaks to forms little crypts inside developing stems. Safe in their hidey-holes, the gall wasps develop into adults and dig holes through the branch to emerge triumphant at a later date. But not if the crypt-keeper wasp has anything to say about it.

Euderus set has to take much the same path in life as crypt gall wasps—they need a safe place to hide while they develop into adults. But rather than piggy-back directly off of the lifecycle of a sand live oak, crypt-keeper wasps manipulate the other wasps that have already done so. The crypt-keepers lay eggs alongside gall wasp larva such that the gall wasps unknowingly trap themselves inside a crypt with their soon-to-be murderers. The two insects develop alongside one another.

When the gall wasp is ready to emerge, the crypt-keeper wasp pounces. It manipulates the gall wasp into digging a hole slightly too small for it to fit through, such that the gall wasp gets trapped partway through the branch. The crypt-keeper wasp has just turned its host into a fleshy plug that it can eat through to escape. Left to their own devices, crypt-keeper wasps often get trapped inside crypts themselves—they’re three times more likely to die there without the digging help from their gall wasp prey.

It’s only fitting that Weinersmith and Egan named the wasp Euderus set after the Egyptian god Set, who (according to myth) trapped his brother in a crypt and dismembered him. And there may be a whole other layer of devious parasitism left to uncover. Some of the crypts also contained fairy wasps—even tinier parasites that sometimes prey on the crypt-keeper’s family members—so there could be three manipulative parasites in play here. And you thought your family was bad.