The Defense Innovation Unit, tasked with bringing commercial tech into the Pentagon, is set to announce in the next few weeks the approval of several more US-made hobbyist-style drones for military use. These drones will be compliant with Congress-mandated rules regarding the origins of their parts, military requirements for functionality, and the commercial industry’s aim of delivering new tech for the military that can be built and sold on a commercial scale to the public.

Currently, and in the past, forces fighting on both sides of Russia’s invasions of Ukraine—first the 2014 occupation of the Donbas and now the February 2022 invasion of the country—have used commercial drones in their fight. These machines, built from kits or purchased as complete and assembled products from a retailer, offered troops on the ground something never before available: cheap, easy access to an overhead view of their own position, and that of nearby enemies.

This kind of commercial drone use in war has hardly been limited to Ukraine. In Syria and Iraq, ISIS used improvised drones and commercial tech to hide and drop bombs since at least 2016, weapons they continued to employ as they were driven out of power by local forces with US support.

Troops in the United States, despite fighting against an enemy using commercial drones to drop bombs, have been discouraged—and then prevented by law—from using the same drones unless they can get special permission to fly them. This fight over “Commercial Off-The-Shelf” (COTS) Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) has meant that while the US remained adept at fielding expensive plane-sized high-end military drones, American forces were falling behind their peers in other militaries and even insurgents and irregular forces fielding the cheapest end of the drone spectrum.

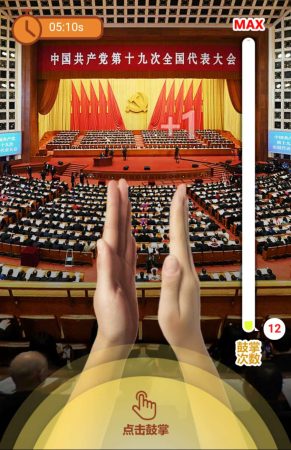

At the crux of this fight is a concern that the sensors and computers for many of the most widely available commercial drones were made specifically in China. Members of Congress, and parts of the Department of Defense, worried that the potential existed for those sensors to collect and share information with someone other than the drone operator. For the troops experimenting with quadcopters, this risk remained abstract, until Department of Defense Inspector General reports made it concrete. (The Inspector General’s office is tasked with auditing and inspecting existing programs.)

“In spring 2018, the Inspector General said, ‘Hey, there are COTS UAS that have cybersecurity vulnerabilities’ and we said, ‘shut up nerd, we’re doing hot drone shit,'” laughs Shelby Ochs, of the DIU. Before joining DIU, Ochs was a Marine officer, tasked with integrating commercial drones into military use, and the Inspector General reports were a hurdle to getting that done. Today, Ochs is program manager for Blue UAS at the Defense Innovation Unit, the team tasked with finding a balance between the legally mandated security constraints on cheap drones and delivering a product to the military useful and cheap enough to be expendable in the field.

Following a second Inspector General report and then an outright ban from the Department of Defense leadership, the use of commercial drones by the military was prohibited in the summer of 2018. A waiver process, by which units could apply for temporary exemptions to the ban, wasn’t approved until December of that year. The problem with the waiver process, says Ochs, was that they “are evaluated by drone, by user, by use case [and] by location. And they’re often good for six months and they require a three-star [general’s] endorsement,” before an approval board hears the request.

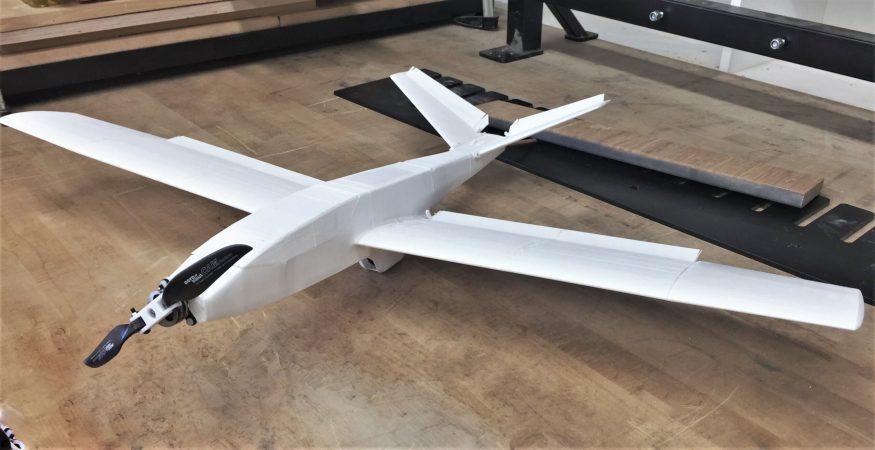

In short, that’s a lot of hurdles to getting approval to fly a cheap drone, the kind people off-duty might just buy and use for fun in their spare time. At the same time, the Army was looking for a drone that could offer the simplest scouting need: looking one hill over, or around the side of a building. Something cheap, simple, and useful enough that soldiers could have it with them in the field, put it in the sky, and see just around the corner without risking anybody getting shot to scout it out first.

In May 2019, DIU gave $11 million to six companies to make the kind of drones the Army was looking for, closer to a commercial price point while still delivering that immediate over-the-hill capability. These companies included established commercial drone makers like Parrot and other entrants like Skydio and Altavian. The announcement promised drones that matched the requirement at the time, but a month later Congress took interest in regulating military drone purchases.

This process was further complicated by the 2020 NDAA, the enormous annual defense authorization act introduced in June 2019 and passed in December of that year. Section 848, the “Prohibition on Operation or Procurement of Foreign-made Unmanned Aircraft Systems,” is just under 300 words, but it dictates major limits on the kinds of drones and drone parts that the military is allowed to purchase or use without a waiver. Chiefly, the act prohibited procuring drones that used “flight controllers, radios, data transmission devices, cameras, or gimbals manufactured” in China, and also prohibited the use of drones that would transmit or store data in servers in China as well.

“Drones are just the same Lego bricks put together in new, interesting ways, right?” says Ochs. “The same radios and cameras and computers.” As Ochs describes it, the limiting factor on making drones acceptable to Congress was a lack of US-made flight controllers, radios, data transmitters, cameras, and gimbals, at least not at the price point needed for these drones to be anything like hobbyist-model cheap.

“The Lego bricks didn’t exist to make the drones cheaper and more capable,” says Ochs.

The Defense Innovation Unit describes drones that meet these requirements as Blue UAS, using the shorthand of “blue” to mean “US.” The program to create Blue UAS is “a holistic and continuous approach that will rapidly vet and scale commercial unmanned aerial systems” for the Department of Defense. In essence, it’s a way to use government requirements and funding to foster the kind of domestic commercial drone industry that can produce domestically made flight controllers, radios, data transmission devices, cameras, and gimbals for drones, at scale and cheap enough to see use on inexpensive drones.

Rather than waiting for a commercial drone market in the US to arrive on its own at selling fully compliant parts and models for military use, DIU funded the development of drones through its Blue UAS. “Sometimes the market needs a little bit of help,” said Ochs. “We’re just providing them the opportunity.”

In other words, the goal wasn’t to reinvent the commercial drone industry from scratch, it was to make sure that there were US-made “Lego bricks” that manufacturers could plug into existing drone templates—ones that met the Pentagon’s desired cybersecurity needs and the mandate passed by Congress.

Looming over the development of Blue UAS is the size and strength of hobbyists drones made in China, most notably the cheap models produced by drone giant DJI. The company, which makes the popular Phantom and Mavic series of quadcopters, has seen its drones used in wars, and is emphatic that this was never an intended or permitted use of the drones. “We don’t market our products toward military use, nor do we sell direct to commercial or industrial users,” DJI spokesman Michael Oldenburg told defense industry magazine C4ISRNET in 2019.

On April 21, 2022, DJI reaffirmed that the same sentiment and said it “has unequivocally opposed attempts to attach weapons to our product.” On April 26, it announced that it was temporarily suspending all business in Russia and Ukraine in light of the war. Both the statement and the suspension affirm what observers have long seen, which is that a cheap and easy-to-fly camera-carrying drone is useful in war, despite the intentions of the manufacturers.

With DJI explicitly not wanting to supply militaries, and with the Department of Defense prohibited from buying DJI drones anyway, Blue UAS is an attempt to spur the market to create cheaper drones with legally compliant parts. Some of this scale will come from military orders, but much of it, as imagined, will also come from the companies being able to sell drones made with the same parts to hobbyists in the US and around the world. These drones may even draw from some supply chains in China for their plastic parts, even while the companies insist all electronics are assembled outside of that country.

Later this spring or early with summer, DIU expects to announce several more drones that have been approved through its Blue UAS process (here’s the current cleared list). What will ultimately matter more than the specific models of drones, though, is the creation of a process and a market that can produce the drone parts the Pentagon wants. In the next few years, if the program lives up to its expectations, when soldiers and marines venture into the field, they’ll be able to toss new drones into the sky, secure in the knowledge that the machines are secure enough for combat, and cheap enough that it won’t be a big deal if the drone doesn’t make it back from the mission.

“If we believe robotics are gonna enable future warfare, then they have to be low cost so that we are able to use them and lose them without fear,” says Ochs.