In three minutes, the Scout drone is assembled. One minute more, and it’s airborne, tossed by a Marine. The flight is short, maybe 20 minutes at the most, but the information gained is valuable, a real-time video of just who or what, exactly, is behind that building a mile down the road. With the area surveilled, the aptly-named Scout drone flies back, and suffers a rough landing, snapping a wing. No matter. The squad can print another back at company HQ after the mission, and have it ready to go in a couple hours.

That’s the vision, at least, behind a new drone program, from NexLog, the Marine Corps next generation logistics team. Last February the team sent corporal Rhet McNeal to a collaborative workspace on a pier in San Francisco to see if modern design tools could build the unmanned scout drone the Corps needs. Except: the Marine Corps already has a hand-tossed drone for scouting missions like this, and it’s had one for years.

The RQ-11 Raven is a flying robot that’s seen action in Iraq and Afghanistan. It’s tossed like a javelin into the air, and if the toss works, it can then fly at speeds of up to 50 mph, at ranges of up to 6 miles, and feed video back to the operator the entire time. (If the toss doesn’t work, and the Raven gets hurtled to the ground, it can sometimes break in an expensive way). It’s also, in the world of military drones, tiny, with just a 4.5 foot wingspan and weighing just over 4 pounds. Still, not everything about the drone is small: an individual Raven drone costs over $30,000, and a whole Raven system including three Ravens and a ground control system can cost up to $250,000.

“The Raven comes in two huge pelican cases,” says McNeal. “I’m in a Combined Anti-armor Team which means that we ride around in trucks a lot. The amount of space we have in the truck for all of our suit, water, more fuel, our actual packs, those things take up a lot of space, and then you have ammo. It makes it where you can’t fit those two pelican cases in there.” Rather than dedicating an entire truck to transporting it, it often just stays behind.

There’s little point to a drone that troops can launch if the troops don’t feel like bringing it along, and then there’s what happens when the troops do fly the drone.

“When it breaks it’s really expensive to fix, and when I say it’s expensive to fix, a section of the wing is like $8,000,” says McNeal, “so a lot of times your battalion doesn’t like using them because they’re so expensive and because they have to write up statements and it’s a lot of paperwork to get that piece.”

McNeal was one of the people who submitted a proposal to last year’s Marine Corps Logistics Innovation Challenge, a program designed to crowdsource ideas about 3D printing and wearable technologies. The “Make Your Corps” challenge asked entrants “With the right tools and instruction, what might a Marine make? Would these solutions improve warfighting capability, either while in garrison or forward deployed?”

For McNeal, the idea was a drone that did most of what the Raven did, but cost a fraction of the cost, and smaller form-factor that fit into flexible packs for transport. To find that idea, McNeal turned to Thingiverse, an online 3D printing commons. There, he found the Nomad design, a simple fixed-wing drone design by Alejandro Garcia. Garcia’s Nomad, published under a Creative Commons license, is designed to carry a GoPro camera, a motor, and it’s built from modular parts. That modular design means it’s easy to reprint damaged components, and simple to collapse and reassemble when needed.

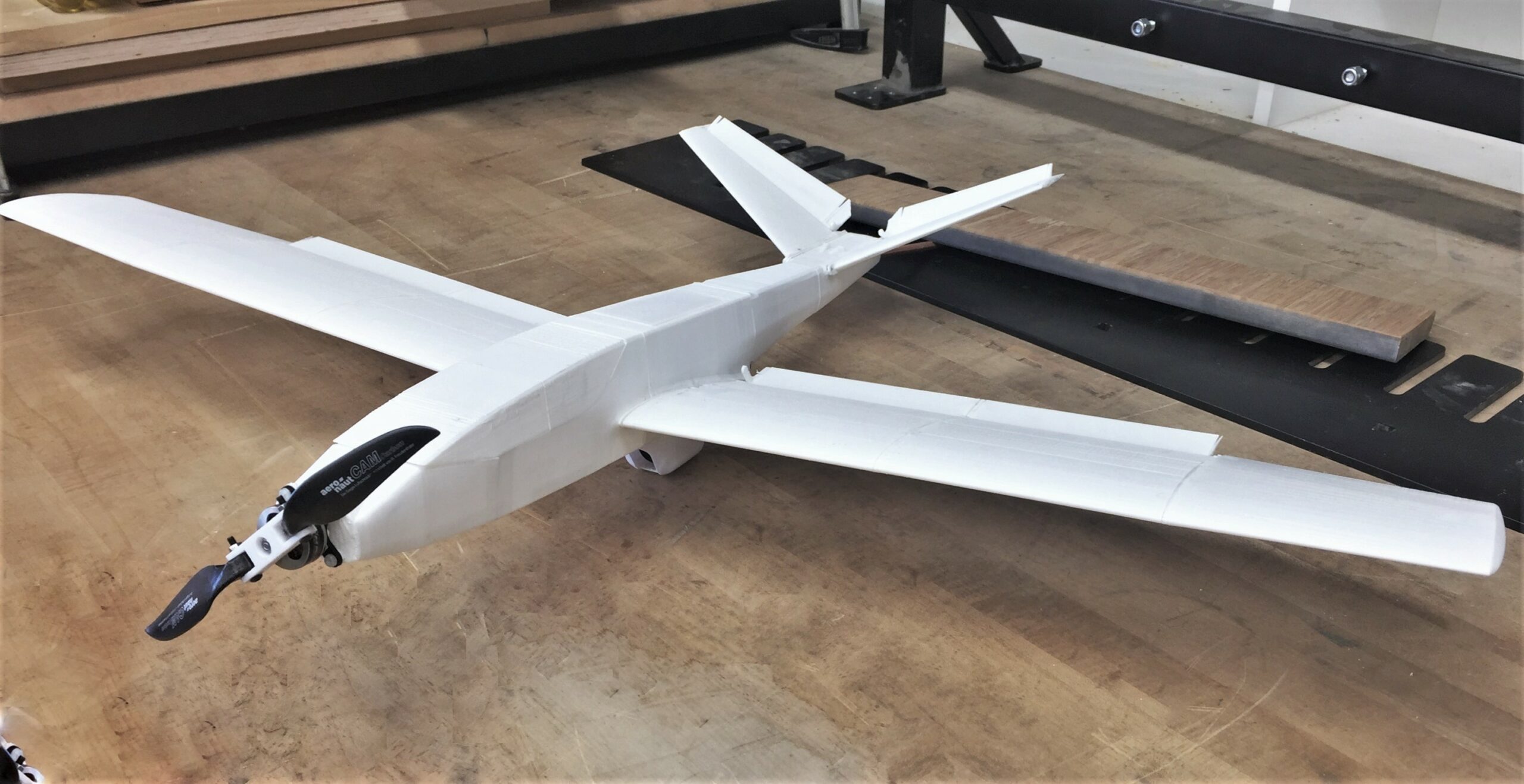

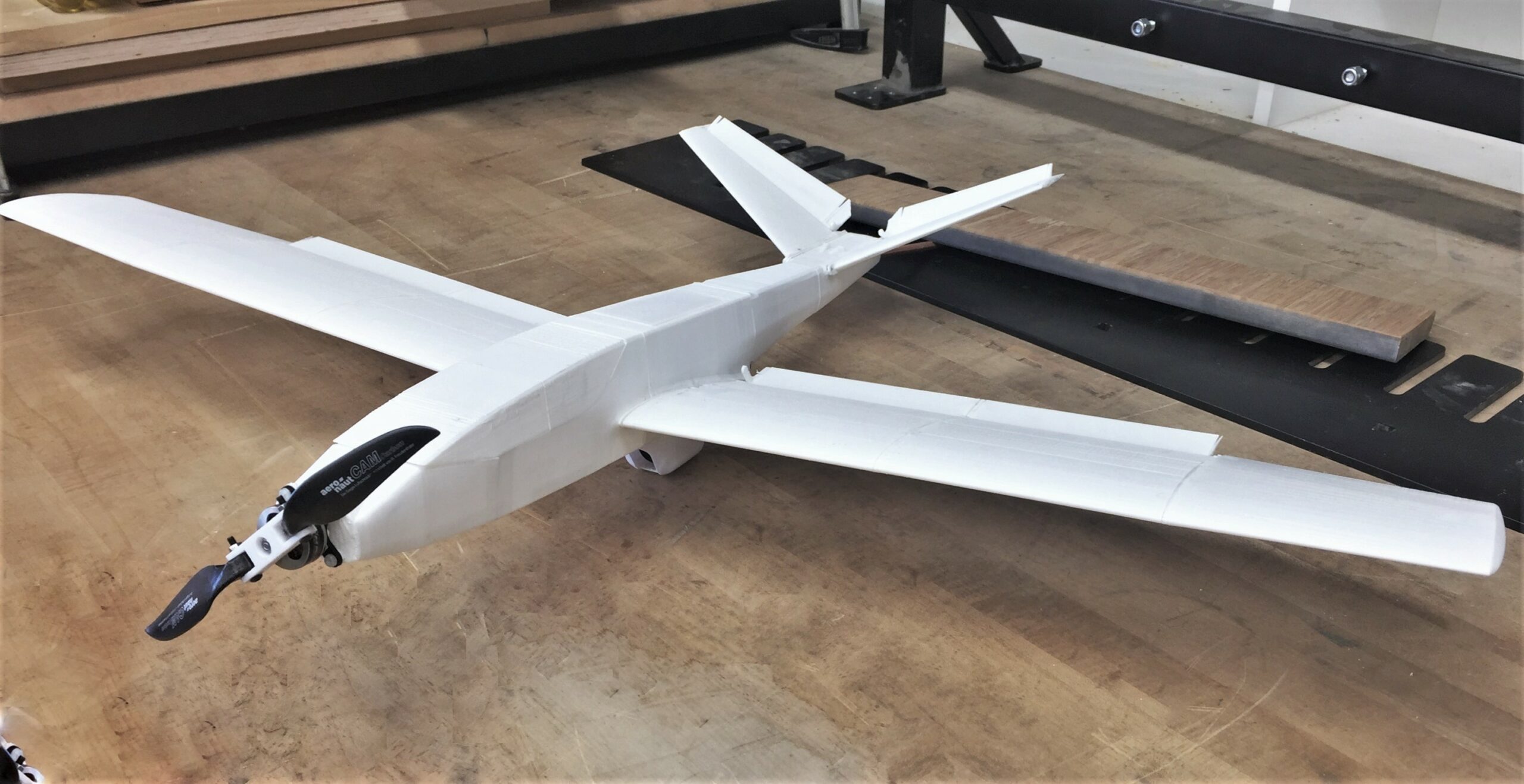

With a modified version of Garcia’s design, McNeal was selected as one of the about 20 winners of the logistics challenge. In February, the Marine Corps partnered with Autodesk’s Pier 9 residency program, and by the time the residency ended in June, McNeal had a new, 3D printed drone prototype, nicknamed “Scout. The end of the residency meant a prototype in hand and design files ready to send to his fellow Marines for feedback, testing, and refinement.

“The entire system is $615,” says McNeal. “If a wing section breaks now instead of being $8000 it’s like $8. That works out a lot better for us.”

Scout uses an open-source flight controller, and open-source software for waypoint navigation. Its only payload right now is a camera, though as designed it’s possible to switch it out. And compared to a drone like the Raven, it’s a more limited device: the range at present is less than two miles, and while it can fly at speeds of up to 50 mph, it can only do so for between 12 and 20 minutes. It lacks a laser to mark targets, and at present the camera it uses can’t see in infrared. Still, it meets the most important requirement: it costs less than $1,000, and can still scout the next hill for the Marines that need it.

That should be enough to make a cheap, easy-to-replace drone that troops feel comfortable bringing on patrol. Which is good, because just buying an existing drone off the shelf may no longer be an option. In early August, the Army banned the use of DJI drones, citing a fear of vulnerabilities and cybersecurity risks in the popular, Chinese-made quadcopters. To build his cheap drone, McNeal turned to commercially available off the shelf parts, which keeps costs low but may carry some of the same risks.

“We don’t have a perfect answer, won’t for a while,” says Captain Christopher Wood, the Director of Innovation at NexLog. “The technology within the drone world is moving so rapidly that it’s hard to predict anything. We need to understand the risk we’re accepting in the technologies we use.”

With its short range and basic controls, the risks in the Scout might be minimal enough to advance the design from a 3D printed prototype to a simple manufactured machine, but one that can still fly with rapidly printed spare parts. That would go a long way to reaching the Marine Corps Commandant Neller’s vision of “a drone in every squad,” and do so at a fraction of the cost of existing designs.

“Trying something new, such as this crowd-sourcing approach, 3D printing, embracing small drone technologies, it’s not that those technologies scare us,” says Wood, “it’s that it requires us to rethink how we’ve been doing business for a long time, and that becomes a little bit uncomfortable.”

Beyond just McNeal’s Scout, the Marine Corps set up three permanent maker labs, one each at 29 Palms and Camp Pendleton in California, and one at Quantico in Virginia. In addition, there’s a mobile maker lab that Wood’s office sends around the country, training eight Marines at a time in everything from welding to 3D printing to electronics building to Raspberry Pi and Arduino. While the Corps doesn’t yet know if it wants a 3D printer at battalion or the squad level, it’s building a foundation to incorporate the tools more generally in the future.

Some Marines are printing replicas of munitions to train troops on what they might encounter in the field. Others are printing drones for training exercises, to practice against the kinds of threats they may face when fighting abroad. All told, according to Wood, there are 40 different Marine Corps units including maintenance, intelligence, infantry units, special operations, and even a tank battalion employing 3D printers on a fairly routine basis. With the tools in hand, the Marines themselves are designing and printing the parts they need, from better radio knobs to missing drone parts to training tools, so they can best perform the tasks they’ve been given.

“I can’t dictate those solutions while sitting in the Pentagon, I won’t understand the full spectrum of solutions,” says Wood, “but the Marines on the ground will, especially when you aggregate them across the Marine Corps.”