Austin Choi-Fitzpatrick is an author and educator whose work focuses on the culture, politics, and technology of social change. He lives in California, holds academic appointments at the University of San Diego’s Kroc School and the University of Nottingham’s Rights Lab, and is the author of several books, most recently The Good Drone: How Social Movements Democratize Surveillance. This story originally featured on MIT Press Reader.

The civil rights movement and Moore’s law are colliding to transform politics. On the street, smartphone technology is being used to document social life as never before, putting power into the hands of the public and making eyewitnesses of us all.

This same technology, bolted onto cheap and easy-to-fly drones, is also providing a birds-eye view of politics on the ground. Indeed, a recent explosion in the availability and affordability of drones has driven an uptick in their use in support of social movements. In the years since the first use of a drone to document a protest—a 2011 event organized against Russian president Vladimir Putin—they have been a consistent presence at protests in societies where democracy is under threat.

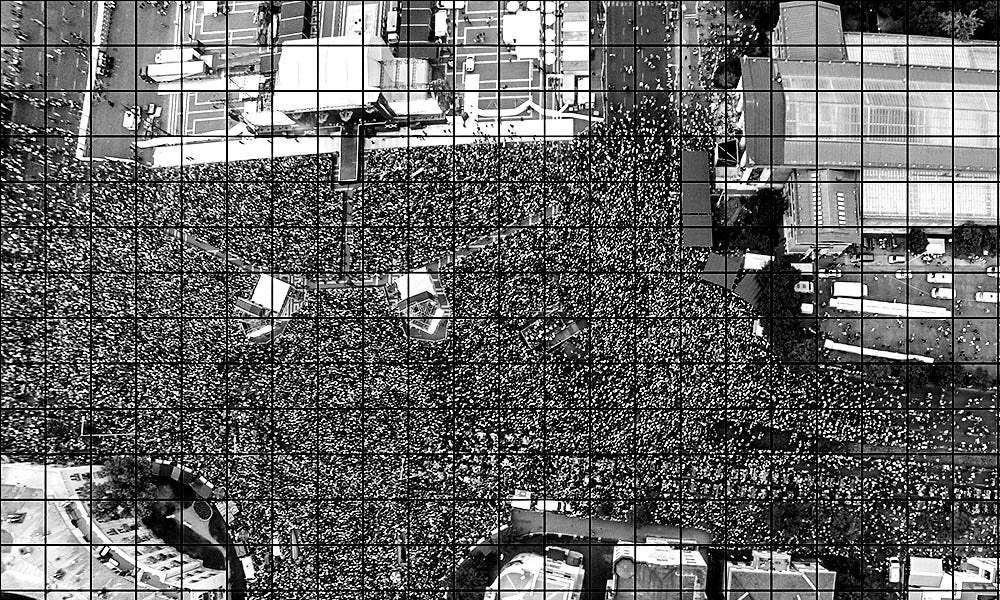

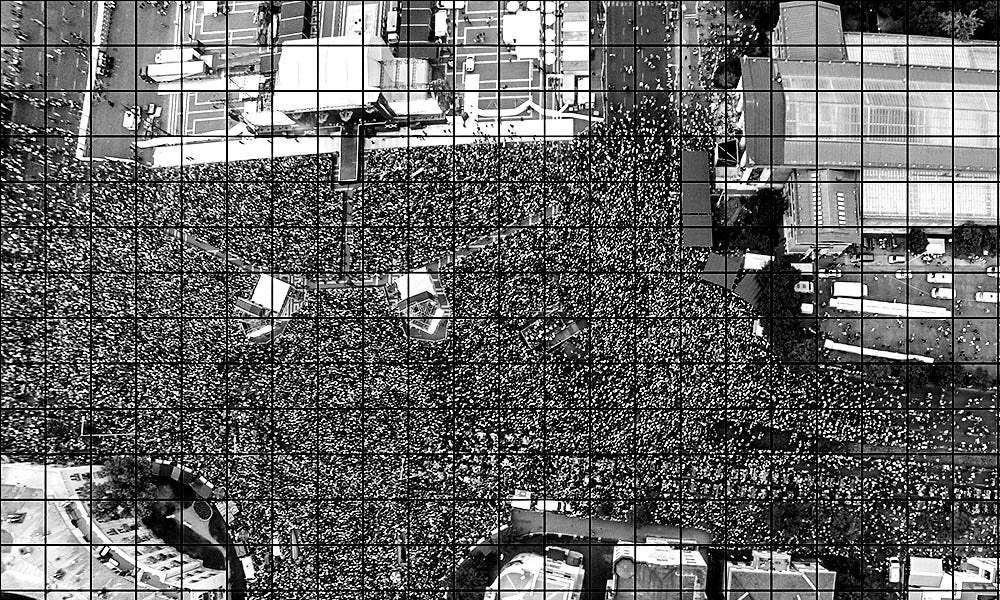

A few years ago, during large-scale protests in Hungary, where media is increasingly controlled by the government, my students and I used a cheap consumer drone to capture footage of tens of thousands of people who had taken to the street to protest a proposed tax on the Internet. The government insisted it was a small crowd of cranks and anarchists, but our footage told a different story—and the proposed government policy ultimately failed.

More recently, drones are being deployed to events where a new vantage point helps activists better communicate their message. An entire article in the New York Times was dedicated to aerial images of anti-racism protests across the country and around the world. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, the imagery was as stark as the message was clear: People everywhere stand in solidarity against police brutality.

Photographer Johnny Miller has traveled around the world in order to capture the abrupt line that divides rich and poor communities. It is a widely acknowledged fact that inequality is rising. Knowing facts doesn’t always drive public action; Miller’s activist photography strikes a more visceral note. Here too the imagery cuts through a clutter of charts and graphs in order to tell an important socio-economic story.

Protesters and journalists all over the world are incorporating drones into their toolkit, and the reason is simple: It allows them to tell a compelling story from a new perspective. Along the way it changes politics on the ground.

Of course, governments are deploying them as well: Earlier this year, the Department of Homeland Security used drones to monitor peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters, making at least 270 hours of footage available to other federal agencies and local police departments nationwide. That footage joins a growing arsenal of high-tech surveillance policing tools. Recent protests may have the unintended effect of pushing police forces off the streets and deeper into less visible and less accountable forms of coercion and control.

In an effort to better understand the other side of drone use, my team analyzed all non-governmental drone use, over a six-year period. We ended up with 15,000 stories, and when we crunched the data two trends emerged.

The first was that the thing many of us fear most—drones being used for spying and committing crimes—is actually quite rare. Those things do happen, and attract significant attention from the press. But at the end of the day, people tend to use technology in accordance with broader social values and commitments, and there are pretty broad social strictures against this kind of bad behavior. Simply put, social norms are fairly stable, so new tech doesn’t automatically unleash anarchy.

The second notable trend was the clear presence of disruptive drone use. By “disruptive” I simply mean the technology is being used to do something that is not politically or socially acceptable—something that disrupts the status quo. Documenting police abuse and highlighting urban inequality are examples that fit that definition neatly. Less disruptive examples include innovative scientists, conservationists, and activists using these small and affordable devices to document deforestation, monitor endangered animals, and track poachers.

Elsewhere, drones are being used to provide public services in hard-to-reach places. Every year I take my students to visit Zipline, a startup that got its start using drones to provide nation-wide distribution of medical supplies across Rwanda. These days you don’t need to go to Rwanda’s capital of Kigali to see Zipline in action. The California-based company is now running an emergency fulfillment center transporting personal protective equipment (PPE) in Kannapolis, North Carolina.

Zipline’s efforts to deliver plasma in Kigali and PPE in Kannapolis is clearly in service of the public good — an example of prosocial behavior — and is politically and socially acceptable: In other words, it’s not disruptive.

The use of drones during protests—especially to hold the powerful to account—is something quite different. When activists used a drone to document large-scale protests at Standing Rock, police responded by shooting them down. When independent journalists used drones to document war crimes in Syria, security forces responded by shooting them down. After we flew our drone in Budapest—and the protest made the cover of the international New York Times—the government quickly passed a new law that would prohibit similar coverage in the future. The reason for these responses is clear: From Standing Rock to Syria, drones are being flown for the public good and are challenging the political status quo.

Drones are in the process of democratizing surveillance in the air, but more must be done to ensure that access to public airspace is open to the public, rather than reserved for the exclusive use of large corporations like Amazon and powerful military interests like Homeland Security. Regulations that would allow this technology to evolve naturally have been stalled by a combination of public concerns related to privacy and security and national security concerns related to predominantly Chinese tech. It may seem like the easiest solution is to just give a handful of licenses to the already-powerful.

As a social movement scholar, I’m hoping this doesn’t happen. Instead I’m rooting for every city that has painted Black Lives Matter in bajillion-sized font that can be seen from space. I’m rooting for every protester that has used drones to monitor police behavior, and for every journalist that has used one to document the sheer size and scale of protests worldwide.

The moment we’re in right now is formed by the complex interplay of the social and the technological. Whether the payload is PPE headed for frontline workers, or an airborne camera trained on law enforcement, new technology, including drones, represent new opportunities to support one another and to hold the powerful to account.