Before vaccines, physicians would blow smallpox scabs up people’s noses or stab them with pus-laced needles to build up their resistance to the virus. It usually worked: Patients would feed mildly ill, then grow immune. But because the pathogen was still living inside them, they could spread it to others.

By the 1930s, medical researchers had figured out how to breed harmless forms of bugs to stuff inside sterilized injections. Since then, vaccines have saved tens of millions of lives, but the pace of development can be glacial. Over the past century, it’s taken an average of 25 years to create a “dead” virus that can protect humans. But when faced with new and rapidly spreading contagions, could a different approach cut that time down to just a few months?

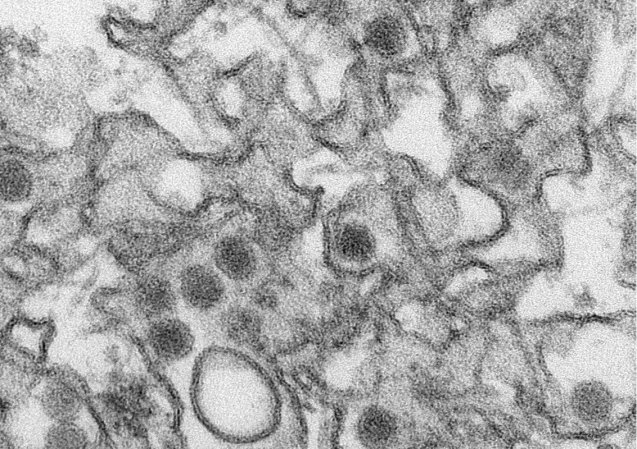

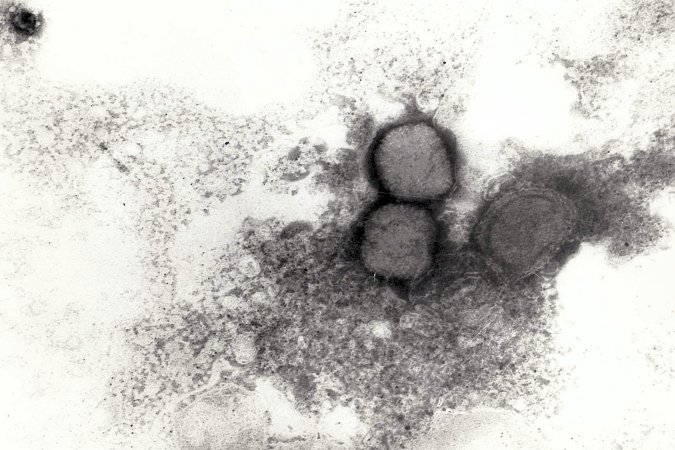

One experimental method involves dosing patients with small bits of viral DNA and RNA instead of a genetically watered-down version of the pathogen itself. By shooting synthesized pieces of a virus’s genetic code straight into the body’s defense systems, we might teach white blood cells to recognize and ambush diseases like influenza, explains Shane Crotty, a professor at La Jolla Institute for Immunology. The workaround could allow new vaccines for Zika, rabies, and more unfamiliar illnesses to reach large-scale clinical trials in less than a year.

The real game changer, though, will come when virologists no longer need to design vaccines that combat specific strains. For infectious pathogens that mutate quickly, immunologists like Crotty might scout out the proteins in a germ’s genetic makeup that don’t change and craft synthetic versions, allowing the body to track intruders even after they’ve morphed. Such treatments may become widely available in the next decade. With a portion of the code already deciphered, drug companies would have what they need to vaccinate people safely and at record speed.

This story appears in the Fall 2020, Mysteries issue of Popular Science.