Our Earth has siblings—the seven other planets in our solar system—but it doesn’t have a twin with which to share its ring of space. Earth sails through its orbit all alone. Other solar systems, though, might have zanier families that chase each other around a sun: twins, triplets, or even quattuorvigintuplets (that’s 24 Earth-sized planets in a single orbit!).

Computer simulations by an international team of astronomers illustrated how two dozen planets can share the same orbit, in research published this spring in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. These wacky configurations can be stable for billions of years, even outliving the stars they’re around. It’s pretty unlikely that nature would create packed planetary orbits, though, which is why researchers suggest a detection of such a system could be a sign of intelligent alien life—possibly even an interstellar message that could exist for eons.

“Our paper explores one additional branch of possible planetary systems that could potentially exist,” says lead author Sean Raymond, CNRS Researcher at the Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux. “I love that it’s so unexpected and weird, and that so many planets can end up sharing the same orbit.”

Multiple planet systems, like our solar system, are often referred to as peas in a pod. But these co-orbiting planets could be “pearls on a necklace,” says University of Kansas astronomer Jonathan Brande, who was not affiliated with the new research.

Nobody had proposed observing two planets in the same orbit, though, until an article posted to the preprint server arXiv last week—but most exoplanet astronomers are skeptical, especially since the signal wasn’t seen in data from other major exoplanet-hunting telescopes like TESS. This paper was written by a group of amateur astronomers who captured observations with small, commercially-available telescopes. “I don’t think it’s the sort of thing you’d be able to pull off in your backyard,” says Brande, regarding the supposed detection.

[Related: These 6 exoplanets somehow orbit their star in perfect rhythm]

There are a few known examples of co-orbits that involve smaller objects. Our solar system actually has a few such strange orbits, known as horseshoe or tadpole orbits, depending on their shapes. Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids—soon to be visited for the first time by the spacecraft Lucy—share the gas giant’s orbital path as tadpoles, oscillating around points before and after Jupiter in its track around the sun. Two of Saturn’s moons, Janus and Epimethus, orbit the ringed planet together in a horseshoe, periodically swapping places.

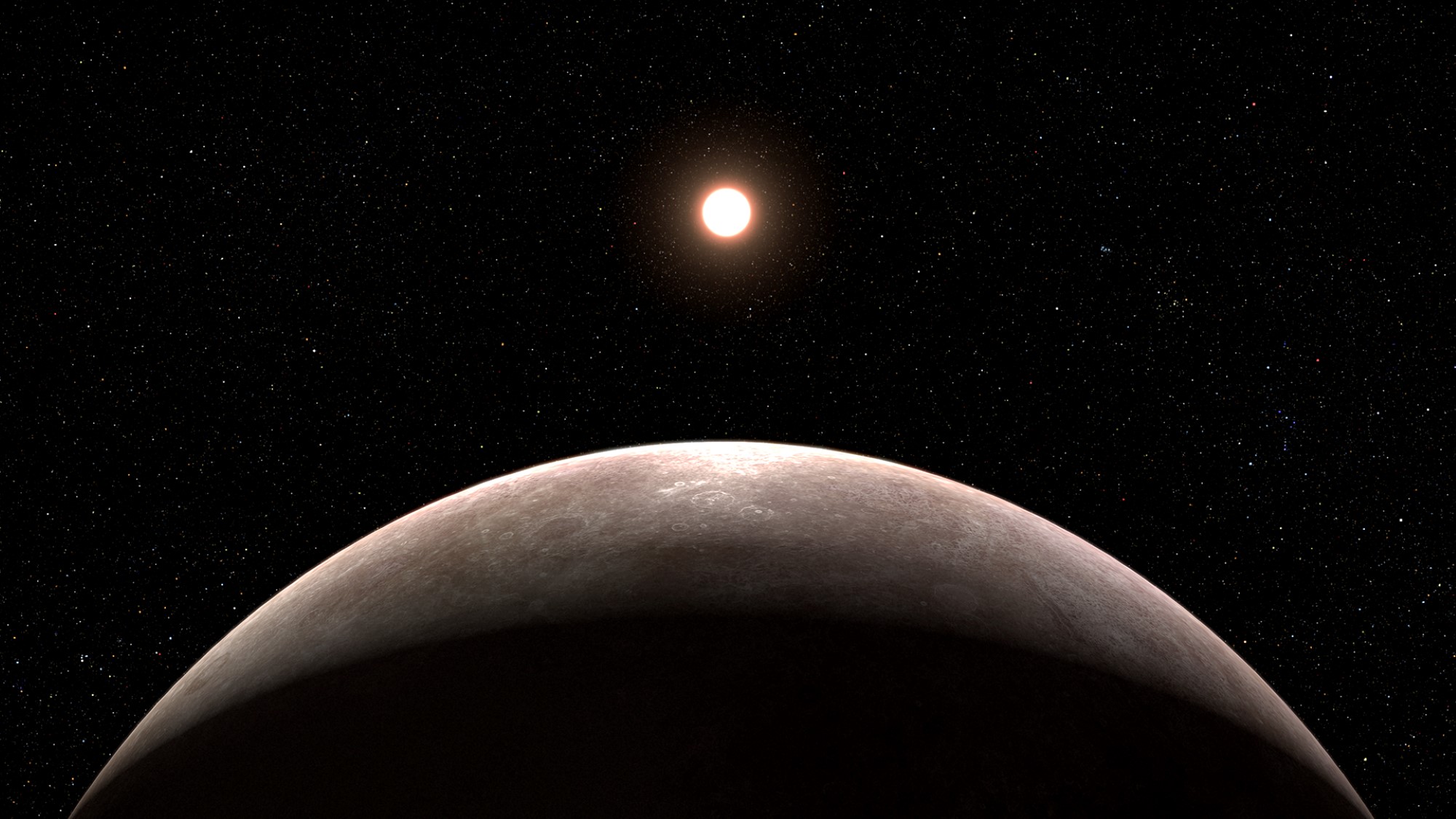

Since objects in our solar system share orbits, it seems reasonable that there might be exoplanets out there that share paths as well. “There are plenty of exoplanet systems in which the planets seem to fill every available niche of stable real estate,” says Raymond. This new research pushes this concept to the extreme, seeing how many planets can cram into the same orbit and remain stable.

The research team’s simulations also reveal that such co-orbiting planets would have distinct signals for astronomers here on Earth to observe. The Kepler Space Telescope and other space observatories can reveal so-called transit timing variations (TTVs), where the gravitational tug between nearby planets ever-so-slightly changes when a planet passes in front of its star. The TTVs from a system of 24 planets with the mass of Earth sharing an orbit would be large enough for astronomers to see, but it would take months to years of regular monitoring to notice the effect, according to NASA Jet Propulsion Lab astronomer Rob Zellem.

Although academics haven’t been persuaded by the latest observation of supposed co-orbiting planets, there is certainly an important role for amateur astronomers in exoplanet science, Zellem adds.“Given the capability of the observers..we could definitely use their expertise,” he says, especially through citizen science projects such as NASA’s Exoplanet Watch.

[Related: This alien world could help us find Planet Nine in our own solar system]

A robust detection of co-orbiting planets could be truly exciting, though—not only an observation of nature’s extreme diversity, but possibly even a sign of alien life. “Something like an engineered co-orbiting planetary might not be unambiguously artificial, but would be weird enough to prompt intensive further study,” says Brande.

The study authors think these odd orbits would actually be a perfect technosignature, or sign of intelligent life beyond Earth. Co-author David Kipping, an astronomer at Columbia University, explains that once an advanced civilization constructs an unnatural ring of co-orbiting planets, it wouldn’t require any power to maintain and would be visible for billions of years—a perfect combo for an interstellar message. “The likelihood of this happening really comes down to whether anyone is out there with the capability and will to do this,” he says. “We have no idea. But if we don’t look, we’ll never know.”