This post has been updated. It was originally published on November 22, 2021.

Asteroids striking Earth have been the subject of many potential apocalyptic scenarios—for which humans have never tested contingency plans, until now.

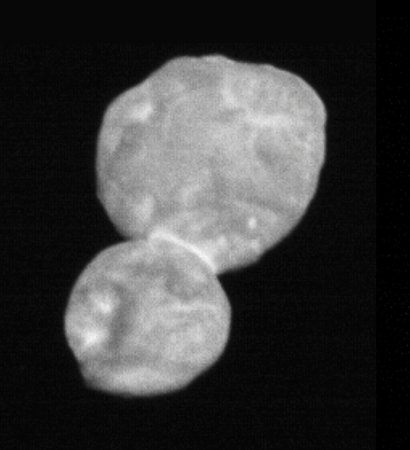

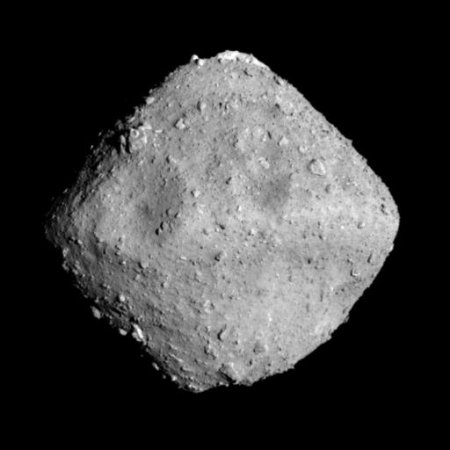

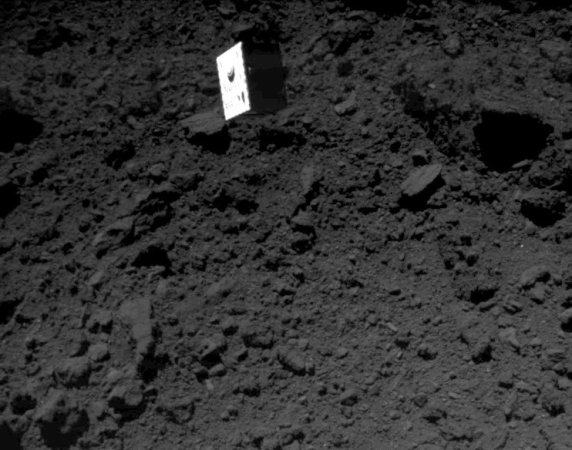

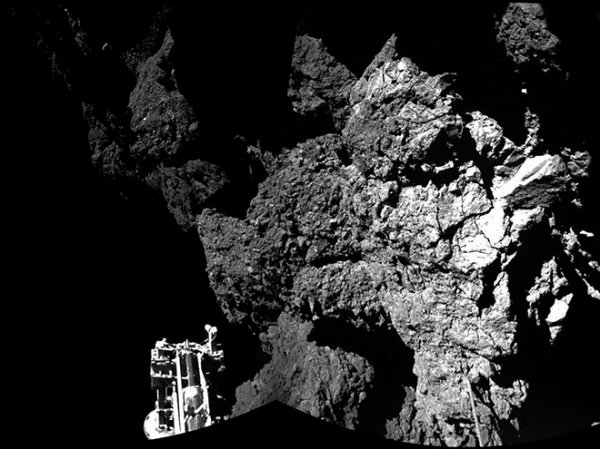

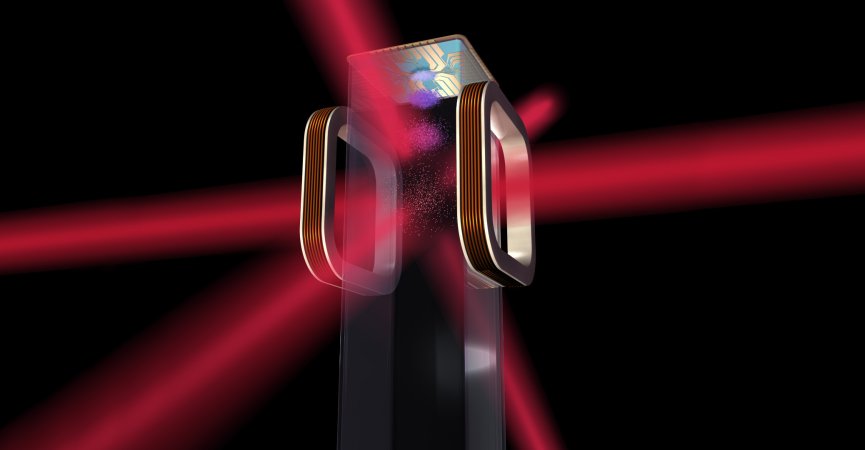

On Wednesday, NASA launched the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), an unprecedented attempt to knock an asteroid slightly off its course. The golf cart-size spacecraft, which took off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Space Launch Complex 4 East at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California at 1:21 am eastern time, will travel more than 6 million miles and collide with an asteroid moonlet—a small asteroid that orbits another asteroid—named Dimorphos in fall 2022. Although the targeted asteroid does not pose any threat to Earth, NASA says the agency is interested to see whether “intentionally crashing a spacecraft into an asteroid is an effective way to change its course, should an Earth-threatening asteroid be discovered in the future.”

“DART is turning science fiction into science fact and is a testament to NASA’s proactivity and innovation for the benefit of all,” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement. “In addition to all the ways NASA studies our universe and our home planet, we’re also working to protect that home, and this test will help prove out one viable way to protect our planet from a hazardous asteroid should one ever be discovered that is headed toward Earth.”

DART separated itself from the rocket’s second stage at 2:17 am eastern time on Wednesday morning, and successfully unfurled its pair of solar arrays around 4 am.

“We’re not out of the woods yet, we’ve got to get out to Dimorphos,” Kelly Fast, a Program Scientist in the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters, told the BBC after the launch. “But this is a huge step along the way.”

[Related: Yes, a killer asteroid could hit Earth]

The DART spacecraft will take a swing at Dimorphos in September or October of 2022. It’s set to hit the space rock at a speed of nearly 15,000 miles per hour, but not with the cinematic goal of blowing it up. Instead, NASA hopes that the force of the impact will change the asteroid’s course by a fraction of a percent—a less glamorous result, but one that will create small but measurable differences in the asteroid’s orbit.

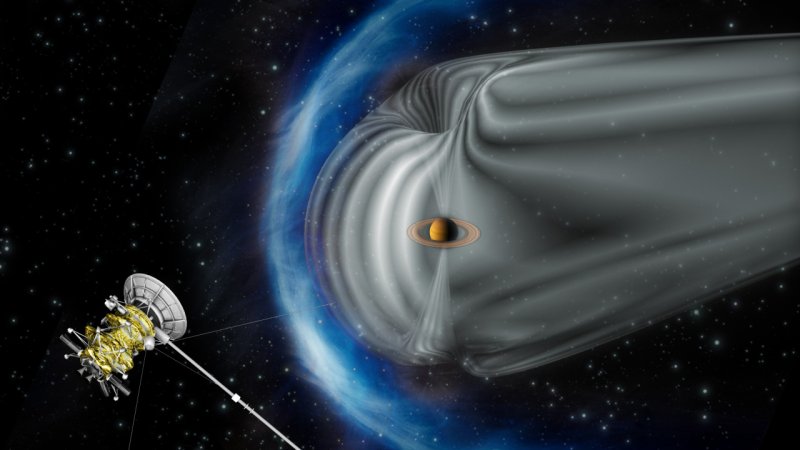

Three years after the impact, the European Space Agency’s Hera mission will conduct a follow-up investigation, measuring Dimorphos’s physical properties in detail to tease out DART’s long-term effects on its orbit.

“DART is a first step in testing methods for hazardous asteroid deflection,” Andrea Riley, DART Program Executive at NASA Headquarters, said in a 2020 statement discussing the mission. International collaboration on a mission such as this is key, she said, especially because “potentially hazardous asteroids are a global concern.”

“Although there isn’t a currently known asteroid that’s on an impact course with the Earth,” Lindley Johnson, NASA’s planetary defense officer, told NPR, “we do know that there is a large population of near-Earth asteroids out there.”

Dimorphos poses absolutely no risk to Earth. NASA’s Earth Impact Monitoring system catalogues potential future Earth impact events for the next 100 years. The Sentry program scans the list of known asteroids and continuously updates impact probabilities. Astronomers have located at least 90 percent of the largest asteroids in our region of space, and none of those pose any risk of impact within the next century.

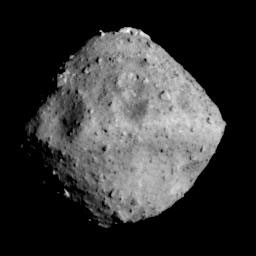

Dimorphos is a smaller asteroid, only about 500 feet in diameter, and those are not so thoroughly catalogued. Astronomers have only found about 40 percent of space rocks under 460 feet wide. None of the those discovered so far has any significant chance to hit Earth. But, if a rock of that size did, it could take out a large city.

“A lot of times when I tell people that NASA is actually doing this mission, they kind of don’t believe it at first,” Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, told NPR. “Maybe because it has been the thing of movies.”