Tuesday’s weather forecast for Southeast Texas—or, as the National Weather Service is now calling it, the “flash flood ravaged areas of the upper Texas coast”—predicts six to twelve inches of rain.

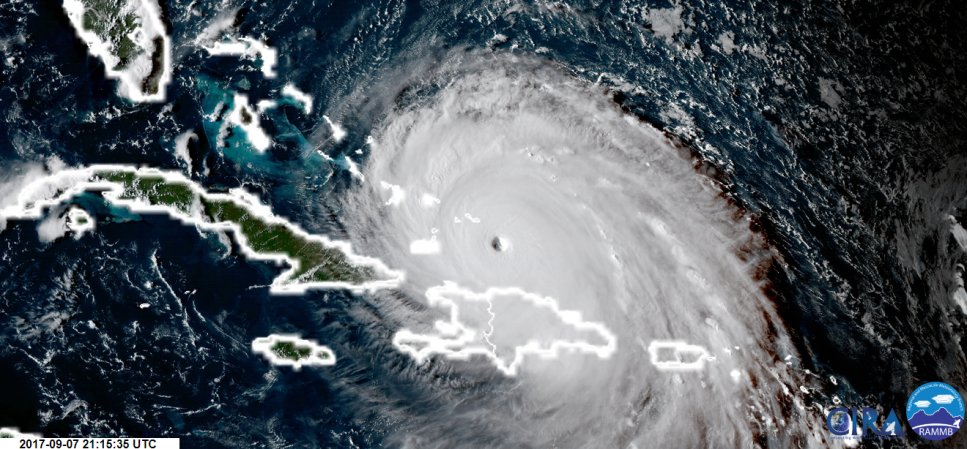

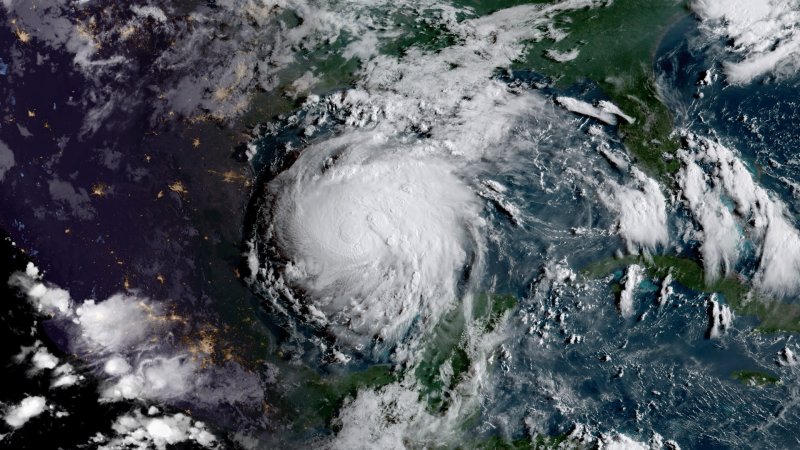

Hurricane Harvey, which has inundated the region since late last week, is back from its brief dalliance in the Gulf of Mexico. While away, it renewed its strength and picked up even more rain. Today’s deluge adds to the 20, 30, and 49 inches of rain that have fallen across the region in the days since Thursday, toppling existing records as part of what some are calling a one in 500 year flood.

It’s hard to watch this disaster unfold without asking how such scales of destruction are even possible. And it’s hard not to answer that question without considering climate change, the hidden factor that has made Harvey much worse than it could have been.

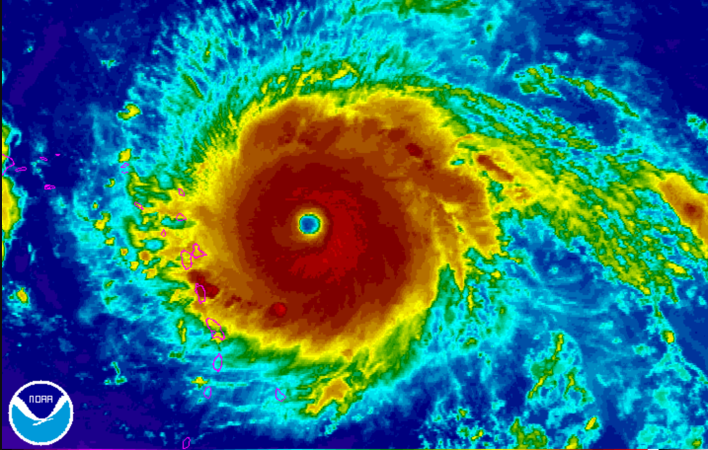

NASA and the National Oceanographic Institute (NOAA) describe tropical cyclones like Hurricane Harvey as “engines that require moist air as fuel.” That need for heat is why the Atlantic hurricane season stretches from June through November. Tropical cyclones only form over ocean waters that maintain a temperature of at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit for 165 feet below the surface, and that’s the time of year when the Atlantic Ocean is most likely to be so warm. Just add wind, and you’ve got yourself a hurricane.

But warmer waters don’t just make hurricanes more likely to form—they also make them more severe. And it’s here where we can see the fingerprints of climate change on Harvey.

“For every degree centigrade the ocean surface heats up, you get about a seven percent increase in water vapor in the atmosphere,” says Jeff Masters, the director of meteorology at Weather Underground.

“In the Gulf of Mexico, where Harvey drew its strength from, the temperature was about a degree centigrade above average for this time of year,” he explains. “And a great part of that extra heat energy was due to the fact that this year, the planet as a whole is experiencing its second warmest year on record.”

In other words, the near-record heat gave Harvey seven percent extra moisture to work with. This doesn’t mean that only 630 billion gallons of the 9 trillion gallons of rainfall (and counting) can be blamed on climate change. That seven percent of extra moisture has a magnifying effect. When a storm has extra moisture, it also has extra energy. And it takes energy to convert water in the ocean into water vapor that can fall as rain.

“The heat energy that it took to create that water vapor is stored in the water vapor as latent heat,” says Masters. “When that water vapor condenses back into rain, that energy is released—and it goes to power the storm. It makes updrafts stronger, so the storm can suck in air all around it. The storm gets bigger and stronger as a result of the extra water vapor in it.”

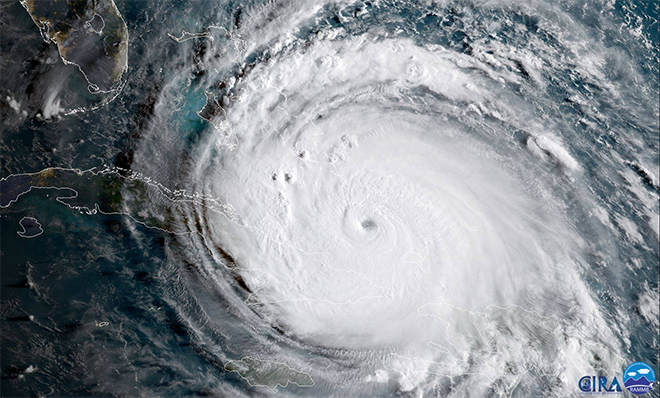

This isn’t the only way in which climate change has made Harvey worse. On his Facebook page, the climatologist Michael Mann points out that the sea level rise contributed to the height of the storm surge.

“That means that the storm surge was half a foot higher than it would have been just decades ago, meaning far more flooding and destruction,” Mann writes. It’s a sentiment echoed by the climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe, who last week noted on Twitter that higher seas could mean stronger storm surges.

Perhaps most critically, much of Harvey’s havoc is due to its lack of movement. If current predictions hold, Harvey will have stuck around the same region of Texas for a week before it clears out. This phenomenon—of bad weather basically getting stuck—has become a recurring theme. Parts of Canada flooded this summer thanks to a similar effect. And in 2016, a slow-moving weather system dropped 20 inches of rain on Lafayette, Louisiana in the span of two days.

In the case of Harvey, Michael Mann says, weak prevailing winds are failing to steer the storm off to sea. Model simulations of human-caused climate change have predicted the changes in atmospheric pressure systems that caused the storm to stall.

Scientists are usually unwilling to credit climate change for a single weather event, especially one that is still unfolding. That’s because weather is a short term atmospheric event, while climate is how the atmosphere behaves over long periods of time. Any toddler is prone to the occasional tantrum (weather) but their behavior over the course of weeks or months (climate) tells you whether the tot is spoiled.

With or without climate change, there have always been hurricanes, droughts, and floods. It can take years for researchers to figure out whether or not climate change was a factor in a given catastrophe. But while we can’t say that climate change caused Harvey, we can say that it has made the storm much worse. Climate change may have been the difference between being hit by a tricycle and being hit by a truck. Both are painful, but only one is deadly.

Of course, the only way to avoid a careening truck is to move out of its way. In the case of climate change, that means finding ways to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are causing our planet to shift. But with many experts increasingly calling this climate our new normal, we must also take steps to adapt our infrastructure. This new normal includes monsoon floods inundating South Asia to kill hundreds, and fires that devour a good chunk of our planet (even, incongruously, Greenland). This new normal includes the 18 inches of rainfall that flooded Southwest Florida over the weekend, and the tropical storm brewing off the Southeast coast of the United States. With three more months of hurricane season left, we can only hope that events as brutal as Harvey don’t become more commonplace.