How well do you know your pets? Pet Psychic takes some of the musings you’ve had about your BFFs (beast friends forever) and connects them to hard research and results from modern science.

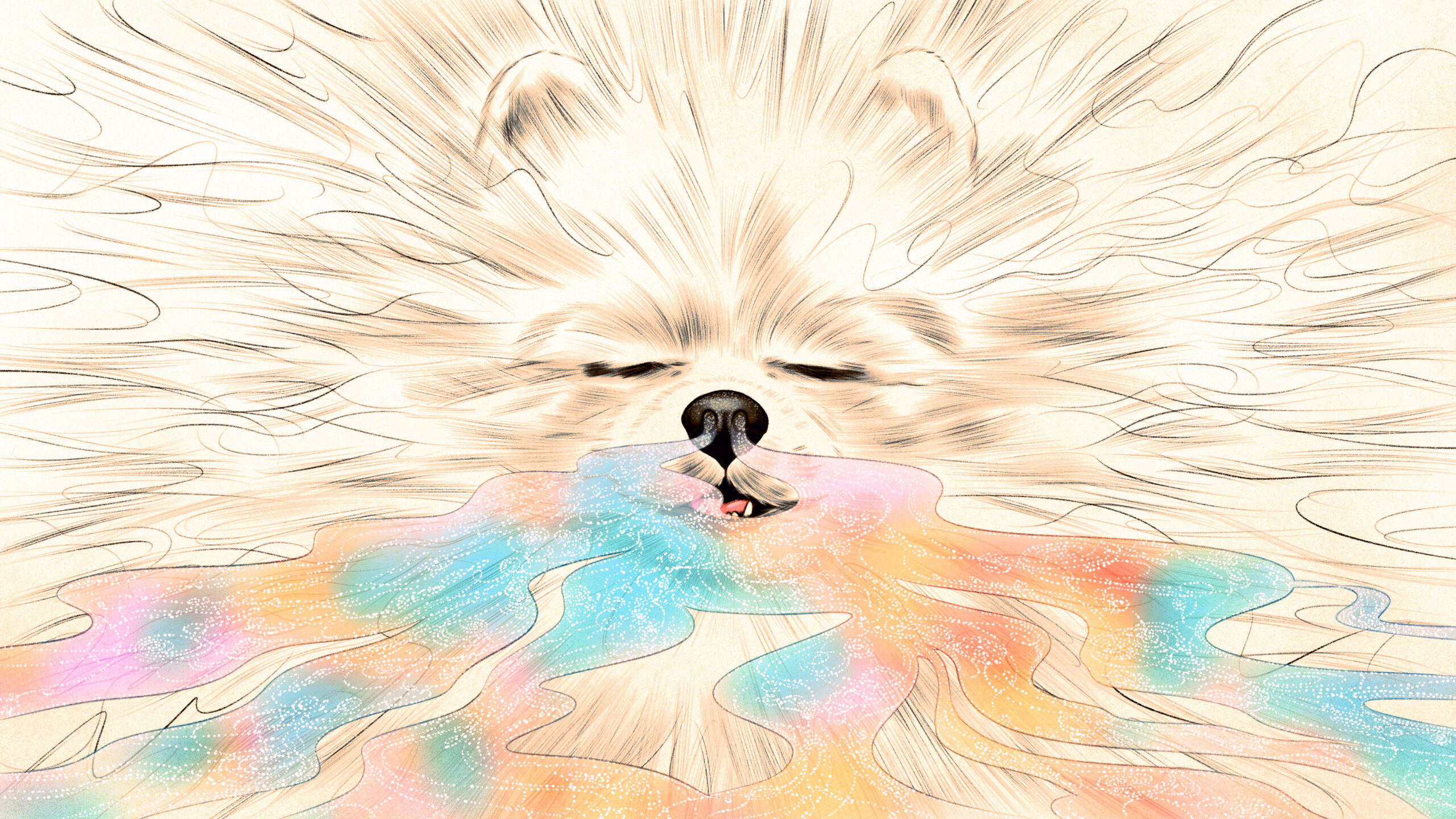

CONSIDER THE MARVEL that is a dog’s nose: that damp, enthusiastic button of adorableness, nostrils attuned to dimensions we barely comprehend.

Now, you might already know that the canine sense of smell is vastly superior to humans’. But sit with that for a while: Try to imagine an existence in which scent is no less important than sight, and your very sense of time and self is entangled with olfaction.

It’s a horizon-expanding exercise—and one that could help us make our sniffy companions’ lives better. “Realizing the importance of olfaction is an easy way to give them a little more freedom to be themselves,” says Alexandra Horowitz, a dog cognition specialist at Barnard College and the author of Being a Dog: Following the Dog into a World of Smell.

The exquisite ability kicks in as air passes through the membranes that cover delicate, scroll-shaped bone structures in their noses called nasal turbinates. Humans also have nasal turbinates—but if our membranes were stretched flat, they’d be roughly the size of a postage stamp. Those of a German shepherd would be the size of a standard postcard.

Such membranes are critical because they hold receptors that sample an odor’s compounds. A human nose contains roughly 6 million receptors; a dog’s nose contains up to several hundred million. A dog’s nose also has anywhere from a few hundred million to a couple billion nerves connecting the receptors to the brain, compared to just 6 million nerves in a human‘s.

The brain’s olfactory cortex, where those sensory signals are processed, is roughly 40 times larger in a dog than in a human. On top of that, last year scientists learned that olfactory pathways extend farther in dogs’ brains than in humans’, and also connect directly to the occipital cortex, where visual information is processed. The connection, which has not been documented in any other species, suggests just how central sniffing is to canine cognition, “rather than a more complementary role as is often described in human functioning,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

“When a dog smells, many more parts of the brain are activated than occurs when humans smell,” says Philippa Johnson, a neuroscientist at Cornell University, who was part of the team that made the discovery.

Such neurobiological sophistication explains extraordinary feats of canine scent detection, like the ability to sniff out disease—dogs have been trained to detect cancer and COVID-19—or fingerprints on a glass slide left outside for a week in the rain and sun. The sense also powers crucial functions like social communication and uncanny spatial awareness. Impressive as those abilities are, though, they don’t necessarily tell us what it’s like to be a dog.

For that, one can turn to an experiment conducted by Horowitz and inspired by the mirror self-recognition test, commonly used to gauge self-awareness across animal species. When a creature uses a mirror to inspect a mark surreptitiously placed on their body, such as a daub of paint on the back of their head, they are considered self-aware. They have a mental image of themselves and have used the mirror to learn about a violation of that image.

Only a handful of mammals beyond humans have passed this test, among them chimpanzees and bottlenose dolphins, but not dogs. Still, because of previous findings, Horowitz suspected that a visual self-image might not be so important to them. Instead, she presented domestic canines with samples of urine: other dogs’, their own, their own altered by another scent, and finally, the foreign odor by itself. The dogs lingered on the altered forms of their urine, as if surprised by the change—not unlike someone seeing an unexpected mark on their reflection in a mirror. But their self-image was not an image at all. It was a smell.

“That sort of scent signature is one aspect of how they think about themselves,” says Horowitz. And as their self-awareness is intertwined with scent, so too might be their sense of time, a possibility suggested nearly two decades ago by psychologists Peter Hepper and Deborah Wells at Ireland’s Queens University Belfast. They wanted to learn whether dogs could detect the direction of an odor trail deposited by passing footsteps.

The dogs did so with aplomb. But how? It had nothing to do with the physical orientation of the footsteps; those had been made on squares of carpet, and when their order was changed, the subjects were befuddled. Instead, the answer seemed to reside in the nature of scent and the way it starts decaying the moment it’s left behind. The dogs were sensitive to these changes, surmised Hepper and Wells, and required just five footsteps to perceive a gradient between recent and less-recent steps—and thus the walker’s direction.

All this speaks to how dogs inhabit a sensory world unlike our own. Even the most ordinary surroundings—a room, a sidewalk, a glade in the park—probably seem very different to them. While these places might seem static to us, Horowitz says, to a dog, they’re a rippling, three-dimensional tapestry of light, shapes, and scents, with every object effusing odors that are further revealed upon nose-first investigation.

“I suspect that to some degree, when they smell something, they form a vision in their brain similar to when we humans see something,” says Johnson. “Smell forms part of their everyday existence and is important in almost everything they do.”

To Horowitz, the added perspective suggests the importance of allowing dogs to engage their noses in everyday life. She points to a 2019 study she co-authored in which dogs who played games in which they sniffed out hidden objects subsequently proved to be in a better mood than those who hadn’t. Although it’s possible that the active pups simply enjoyed the interaction rather than the sniffing, it makes sense that using their noses enriched their lives.

Many dogs, however, live in less enriching circumstances. They spend most of their time in relatively scent-impoverished indoor environments and then, when taken outside for a walk, are hurried along at a pace that’s more about their caregiver’s interests than their own. Even just a cracked-open window can make a difference, says Horowitz, though she tries to let her own companions, Quiddity and Tilde, sniff to their hearts’ content while exploring on a stroll.

“I very much encourage that on at least one of the walks you take with your dog, you let them indulge the things they want to smell, just as you would in wandering through a museum and not forcing someone to keep their eyes straight ahead,” she shares. “This is their moment, when you’re outside and there’s all sorts of stuff for them to see and smell. Give them a chance to do that.”

Read more PopSci+ stories.