What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s newest podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits iTunes, Soundcloud, Stitcher, PocketCasts, and basically everywhere else you listen to podcasts every Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster.

Fact: Macaroni and cheese dates back to at least 1390

My obsession with mac and cheese started long before I edited Claire Maldarelli’s story about why your brain loves the combo more than macaroni or cheese alone. But working on that article got me hungry for more than just food—I wanted knowledge. I wanted all the weird macaroni facts I could find so that I could share them with you. And oh gosh, there are plenty of them out there, as you’ll find on the podcast (and right here!)

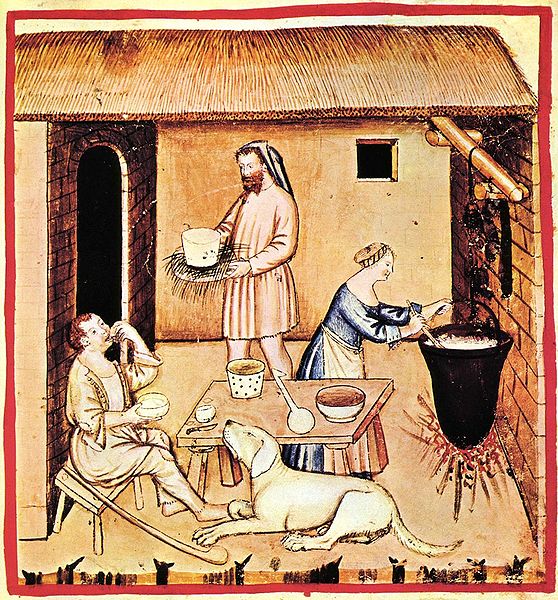

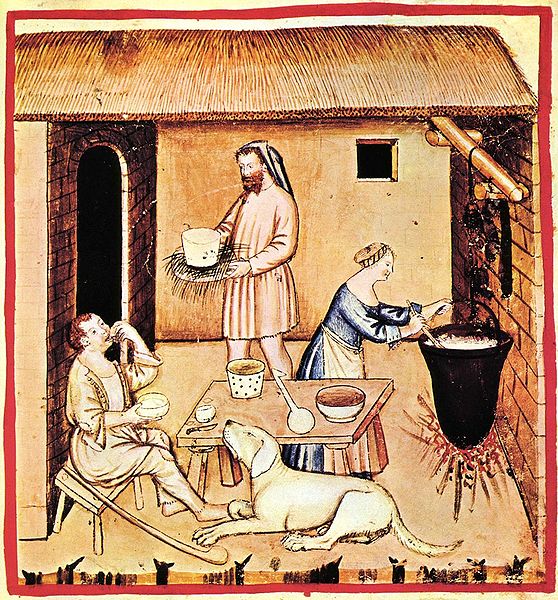

I found out that the oldest known written recipe for the cheesy, carby dish dates back to the royal court of Richard II, around 1390. In the scroll, the Forme of Cury, the recipe for ‘Macrows’ involves boiling thin strips of dough, and layering the result with butter and cheese, kind of like an even older recipe for lasagna.

Pasta, butter, cheese—it doesn’t get much better than that. We don’t get into it on the podcast, but I know that there are a world of mac and cheese recipes out there, whether baked, boxed, bread-crumbed and bechamel-ed. What’s the weirdest, most delicious mac and cheese you’ve ever encountered? Inquiring stomachs would love to know. Give us the 411 on Facebook.

Fact: The history of science is full of people trying to do magic (including sex magick)

When most of us think of the early days of American rocket scientists, we evoke visions of rowdy, earnest boys launching volatile explosives from their backyards and dreaming of trips to space. Jack Parsons was one of those folks—in fact, he was one of the cofounders of what is now NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL)—but he’s also known for his commitment to the occult. I first heard about Parson’s escapades in one of my favorite fictional podcasts, and the stories of his involvement in Aleister Crowley’s satanic churches and his friendship with pre-Scientology L. Ron Hubbard are 100 percent true.

A few books exist on the subject, and it’s not as if NASA has kept Parsons a secret. But the fact that he was considered a bit of an embarrassment to his colleagues (what with all his sexually-charged magical ceremonies and Pasadena) definitely derailed his career. And it didn’t help that his offbeat interests got him swept up into the anti-communist scare of his day; the explosives expert died working on a movie special effect at the age of 37, having been barred from work on his beloved rockets.

But the most interesting thing about Parsons isn’t that he tried to do magic (or magick, as Crowley’s crowd preferred to say), rather, its why he did it. Parsons thought that quantum mechanics could explain the powers he tried to conjure. To him, trying to perform magical rituals was not contrary to his activities as a scientist. He saw a world on the cusp of sending men and women into space—a world that had figured out how to split an atom. And to him, that was a world that could conceivably be on the verge of uncovering a connection to omnipotent, previously unknowable power. In this episode, I also highlight a few other famous scientists whose love of the unknown led them to dabble in stuff we now scoff at. One example is Thomas Edison, who seems to have thought he could use electricity to commune with the dead. He didn’t think a belief in ghosts was anti-science, but rather suspected that some kind of physical particle might make up a person’s “spirit,” and that it must remain (as all matter does) even after death. One wonders what things we find plausible as being 10 or 50 years out today might be laughable with another 100 years of scientific perspective.

Fact: An apparent case of contagious writer’s block lasted for three decades

From 1964 until his death in 1996, Joseph Mitchell went to work at The New Yorker magazine more or less daily. But while his editors and readers eagerly awaited fresh work from the reporter, who had once produced articles and even books to great acclaim, he never published another word. Mitchell, it seems, had pretty much the worst case of writer’s block of all time. Even worse, the circumstances in which it bubbled up made his writer’s block appear to be the result of… contagion.

This is about the most cursed story you can tell another writer, but I forged ahead anyway—bad juju be damned. It turns out, writer’s block is a very real phenomenon, but probably not a contagious one. (Though, as we’ve learned on previous episodes of the podcast, just about any idea can be contagious.) Even more interesting, there are some pretty solid remedies for writer’s block—assuming you fit into one of the four types of blocked writers psychologists identified in the 1970s and ’80s.

Oh, and in case you like homework: In 2013, The New Yorker posthumously published an article Mitchell wrote in the 1960s or ’70s, but kept to himself, at least until his death. It’s called “Street Life”. And yes, the word “haunt” appears four times.

If you like The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week, please subscribe, rate, and review us on iTunes. You can also join in the weirdness in our Facebook group and bedeck yourself in weirdo merchandise from our Threadless shop.