What’s the weirdest thing you learned this week? Well, whatever it is, we promise you’ll have an even weirder answer if you listen to PopSci’s newest podcast. The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week hits iTunes, Soundcloud, Stitcher, PocketCasts, and basically everywhere else you listen to podcasts every Wednesday morning. It’s your new favorite source for the strangest science-adjacent facts, figures, and Wikipedia spirals the editors of Popular Science can muster.

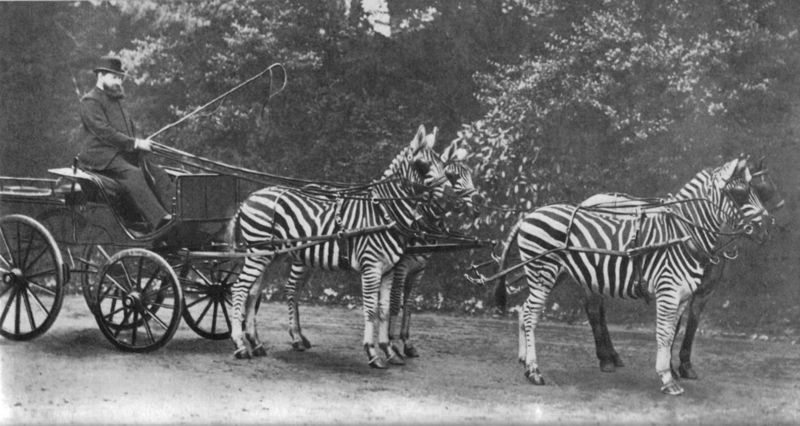

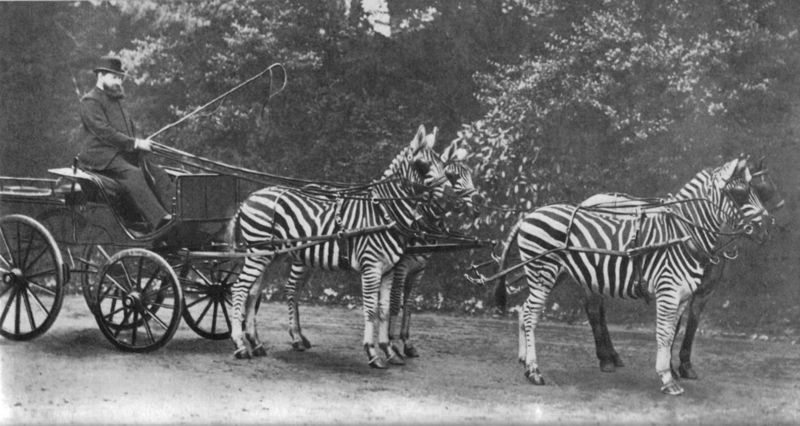

Fact: One intrepid zoologist once rode a carriage pulled by zebras past Buckingham Palace

Everybody wants a pet fox, as evidenced by the longtail success of the PopSci article “Can I have a pet fox?” So I was tickled when Neel V. Patel pitched this update on fox domestication genes. Reading up on the domesticated foxes that, some 40 generations in, have turned positively puppy-like, I started to wonder: what determines whether or not we can domesticate an animal?

No Weirdest Thing fact-finding mission is complete without a weird internet rabbit hole, and I found mine in Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild of Tring. The zoology enthusiast is famous for his contributions to collections of preserved animal specimens all over the world, but he’s also famous for riding a carriage pulled by zebras past Buckingham Palace. But despite Rothschild’s impressive efforts to tame the striped creatures, they staunchly refuse to be domesticated.

Fact: In late-18th- and early-19th-century England, people really enjoyed inhaling laughing gas

By: Sophie Bushwick

In 1798, Humphry Davy, a young poet and aspiring physician, became the supervisor of the newly-established Bristol Pneumatic Medical Institute, a center for medical treatment and research. Davy quickly realized that the Institute’s regimens were not based on actual trials or experiments, so he embarked on a course of research into various inhalable gases. His first subject: himself.

After undergoing fainting fits, nausea, and a near-death experience with carbon monoxide, Davy eventually decided nitrous oxide, N2O, would be the safest substance to test on himself and others. It was also the most fun. “This gas raised my pulse, made me dance about the laboratory as a madman, and has kept my spirits in a glow ever since,” Davy wrote. Thanks to reactions like this, people would eventually dub the substance laughing gas.

Davy loved inhaling nitrous oxide; during one period he breathed it up to three or four times a day. He wrote poetry under the influence (“On Breathing Nitrous Oxide”), experimented with combining alcohol and N2O (apparently it reduced his hangover), and spent some time saturating his lungs in a portable gas chamber.

In addition to self-experimentation, Davy tested other subjects, pioneering a blind experimental method. Without telling volunteers whether they were inhaling nitrous oxide or plain air, he recorded their physical reactions and asked how they felt. He also gave gas to his friends, including female acquaintances (which gave rise to rumors that this substance made women hysterical and removed their inhibitions) and the poets Robert Southey and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Many of them enjoyed the experience as much as Davy did; Southey wrote, “It has made me laugh and tingle in every toe and finger-tip.”

Although Davy realized nitrous oxide could make a person lose consciousness and then revive without ill effects, he didn’t leap to applying laughing gas as an anesthetic during surgery. (It wasn’t used this way until 1844, after Davy’s death.) But he did publish the results of his detailed experiments—to mixed reactions. The popular press, and political cartoonists, lampooned his work, implying that nitrous oxide induced not only hilarity, but also sexual debauchery.

However, this negative press did not damage Davy’s career. He went on to make his name as a famous chemist, using electricity to isolate seven elements, including potassium and calcium, for the first time. As an inventor, he also created a new lamp that miners could use safely underground. And he continued to write poetry.

The oldest instruments are all bone flutes

That sound you’re hearing is the haunting music of the Divje Babe flute, which many experts consider to be one of the oldest known instruments on Earth. Dating back to a Slovenian cave some 43,000 years ago, the flute is crafted from a cave bear femur. (Unless it’s just teeth marks from a hungry cave bear murderer, as other archaeologists suggest.) Listening to its spooky tune, I accidentally unlocked an ancient curse, and tumbled down a rabbit hole about the origins of music. While little is known about why we sing, scat, or play the tuba, one thing’s for sure: humans love turning bones into flutes.