You may not think too much about swarms of aggressive drones, but military planners do. That’s because a swarm of drones could confound defenses, as the formation could keep flying even after individual drones inside of it fail. For military experts tasked with securing bases against assault, preventing damage from a swarm of explosive-laden drones means stopping the entire swarm, not just removing a few moving pieces. That is why the Air Force is testing a new weapon, one that targets the electronics that makes the swarm work, all at once.

To defeat swarms like this, the US military is developing THOR, or the Tactical High Power Operational Responder. Built for the Air Force Research Laboratory, THOR is one way that bases or other military installations might defend themselves against aerial robots traveling in groups.

Officially, THOR is a “counter-swarm electromagnetic weapon” that “provides non-kinetic defeat of multiple targets.”

Stripped of jargon, this means that instead of using bullets or explosions to disable robots, THOR turns to messing up their electronics, specifically by hitting the gaggle with a high-powered microwave. The effect of such an approach against an electronic system can vary, from temporarily impairing the ability of the drones to communicate with one another all the way up to frying the electronics and rendering entire machines in the swarm broken.

[Related: The US military’s heat weapon is real and painful. Here’s what it does.]

This disruption, a cone-shaped blast against electronics, happens in a nanosecond and with immediate results, the Air Force boasts. And silently, too. The success projected is one of technological triumph against a new enemy. The imagined outcome is a sky full of robots approaching the THOR weapon, and then without any external indicator of change, the robots all fail in a host of ways, some crashing to the ground on fried computers, others staggering in place or veering of course.

THOR acts, and then the robotic smog clears.

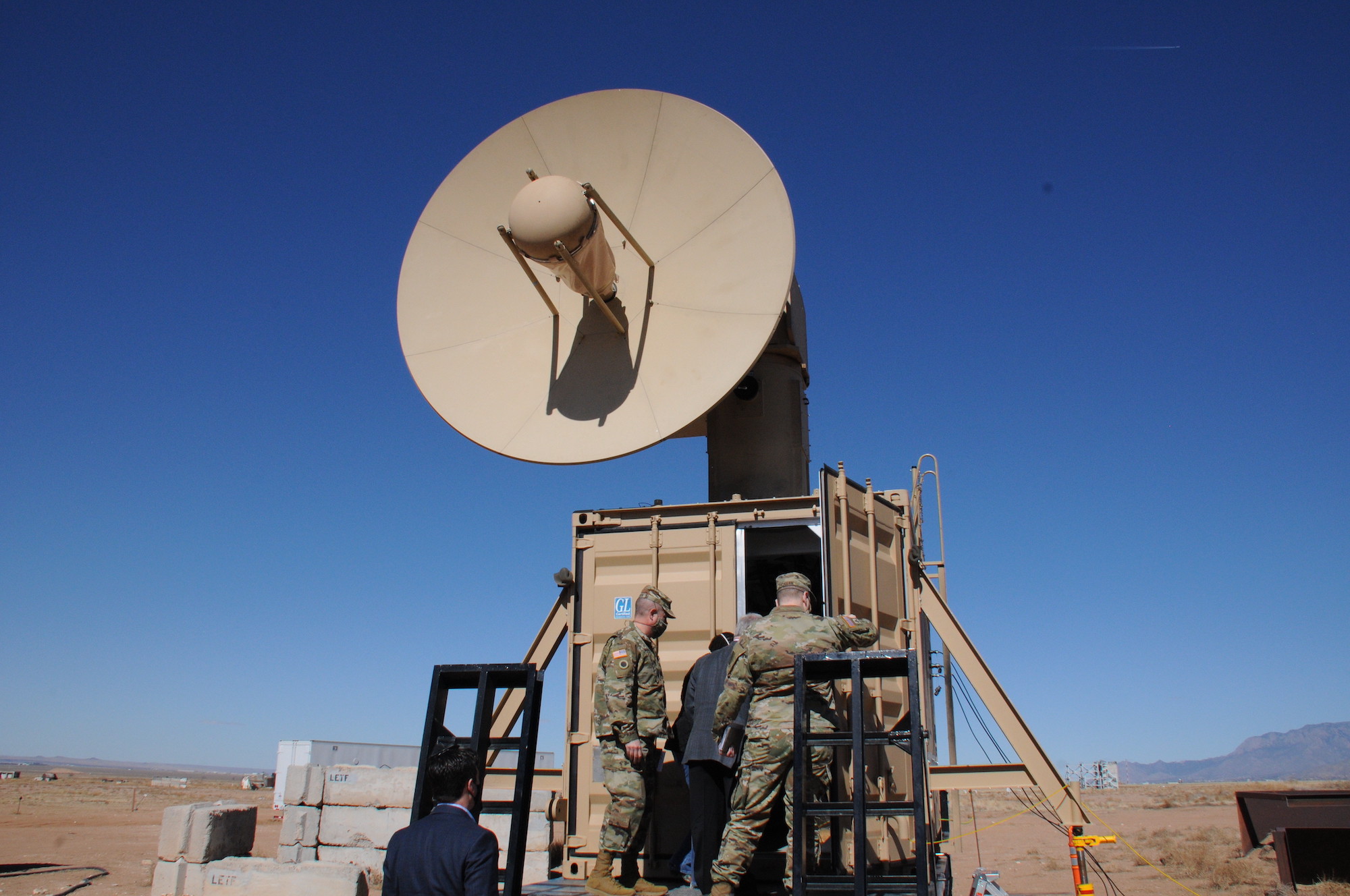

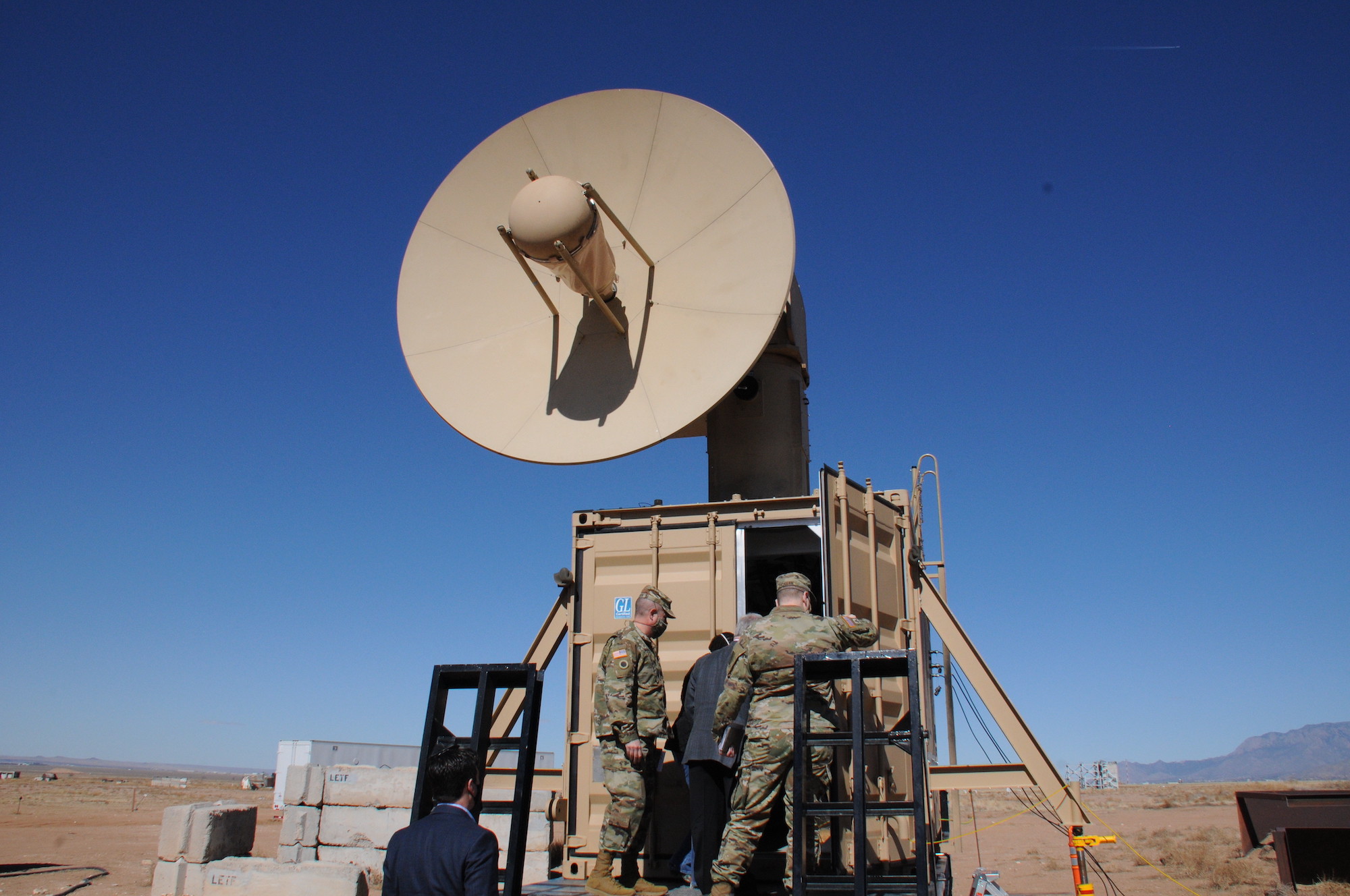

On the outside, THOR looks like nothing so much as a radar hatching from a shipping crate. Its body is small by military standards. The entire system can fit inside a 20-foot-long shipping container, which itself can fit inside a C-130, the Air Force’s durable transport plane. That’s important, because it can reach places most likely to want a THOR. These are bases remote enough to risk a swarm attack, yet not so remote that they would be too small to be targeted.

Once offloaded from a plane, THOR could be driven into position on the back of a flatbed truck, so it’s not entirely at the mercy of runways. Still, it’s a big piece of equipment, and developing it wasn’t cheap. While the Air Force doesn’t list a unit price, it says the development cost was $15 million.

[Related: The Coyote swarming drone can deploy for aerial warfare—or hurricanes]

In February 2021, the Air Force tested THOR in an exercise south of Albuquerque, at Kirtland Air Force Base. Army observers were in attendance, suggesting that the Army itself may look to THOR as part of a comprehensive approach to protect against drones.

Previously, the Air Force demonstrated THOR for a crowd including reporters in 2019. At that demonstration, the THOR system knocked out a single hovering drone. And in December 2020, Richard Joseph, the Air Force’s chief scientist, said that THOR had been deployed and tested in Africa for base defense.

Part of the particular danger of drone swarms is the relatively low cost of components. Useful quadcopters can be found for a few hundred dollars or less, and it takes only a little modification to fit a small explosive payload to one. In 2016, an abandoned ISIS drone factory contained lots of cheap, off-the-shelf components for individual drones, which had been used to deadly effect in its earlier war effort in Iraq. While none of these drones were set up to swarm together, non-state actors have launched massed attacks featuring multiple drones working together, which have proven effective against more traditional anti-air defenses.

[Related: Russia Is Working On An Anti-Drone Microwave Gun]

This is to say nothing of the potential for cheap, acrobatic swarms. A company in China set a drone swarm world record in September 2020, with 3,051 drones, and then surpassed that with a 3,281-drone swarm in March 2021. The same technologies that make drones aesthetically pleasing in the sky, or allows them to ominously assemble into a flying QR code, can also coordinate many drones to fly in formation against a fixed position and, if so equipped, cause harm.

Shooting down a single small flying machine is hard, if doable. Shooting down an entire teaming sky of robots—a murmuration of drones, some potentially carrying explosives—is a danger that seems to demand special weaponry. Thus, THOR.

Figuring out a way to stop a swarm is increasingly a military preoccupation. It’s an abrupt shift from decades of working on fighting expensive, high-end aircraft with increasingly sophisticated missiles, and it will take different tools to work.

If THOR continues to be successful in trials, it is possible that the Army and Air Force could field THOR units as early as 2024 for more battlefield testing, with a possible formal entry into service slotted for 2026. Microwave weapons may not stop the development of swarm drones entirely, but they may at least stop a given swarm at a crucial moment.