Last week without fanfare, a 230-page military document (PDF) appeared in the public domain. The document, authored in May 2016, is a comprehensive list of rules, standards, and definitions governing the heart of what the military does: picking targets, and making sure those targets are valid and within the bounds of the laws of war.

The Pentagon isn’t exactly sure how the document ended up online. On Monday, Nov. 15, the nonprofit Federation of American Scientists ran a short post on the newly public document. Entitled “Joint Chiefs Urge “Due Diligence” in Targeting the Enemy,” the post highlights the central theme of the instruction manual: attacking the wrong target in war can have negative consequences for the United States and the countries it works with. This is a simple point, repeated and clarified through page after unredacted page in great detail, setting not just the rules but the very language that America’s military uses when fighting wars and deciding which object or person to fire at.

This doesn’t govern all the rules for use of force abroad; as Steven Aftergood of the Federation writes, “The manual applies to the Department of Defense and the military services. It does not govern lethal operations by the Central Intelligence Agency.” Most significantly, that means some operations, like targeted drone strikes flown for the CIA, are not governed by this manual.

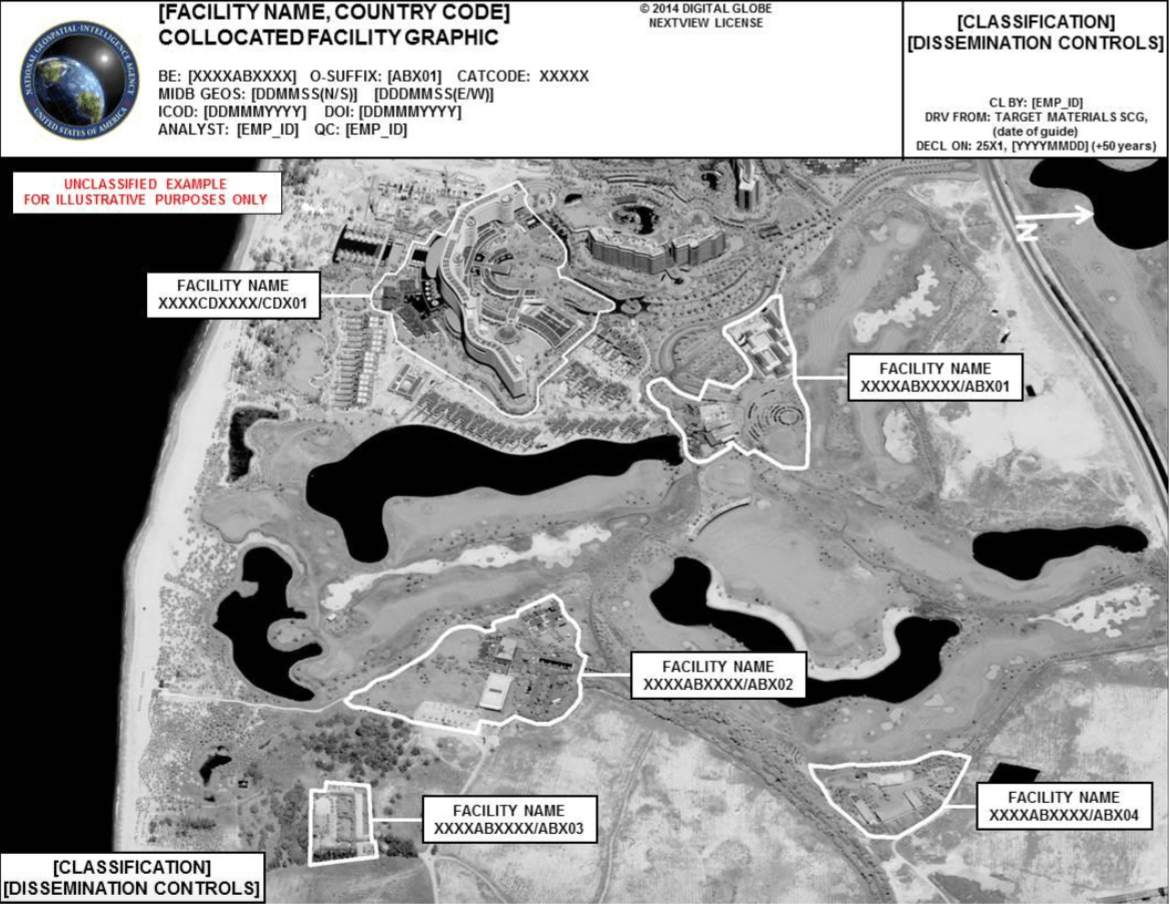

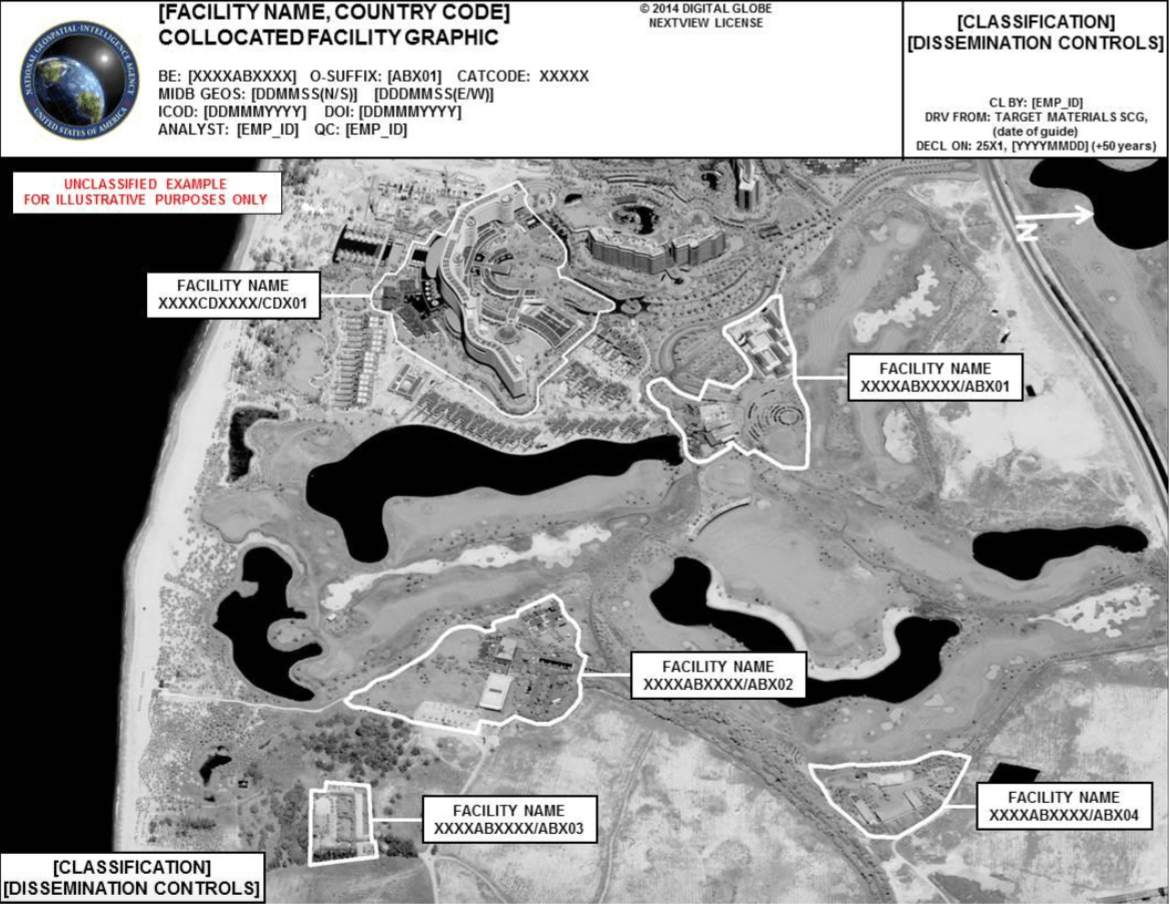

What the manual does cover is almost everything else, from air forces and airfields, to the difference between a facility and an installation. There are rules for documenting what gets selected as a target, and guidelines for properly citing sources in an Electronic Target Folder, or the document used to show evidence that a given building, is, say, a cache of weapons used by an insurgent group, instead of a general store visited entirely by civilians.

The manual instructs commanders selecting targets to answer specific questions, like “How will the target system or adversary capability be affected if the target’s function is neutralized, delayed, disrupted, or degraded as planned” and “What is the expected adversary reaction to loss or degradation of the targets and target system’s functions?” In order for a target to be approved by intelligence agencies, like the CIA, NSA, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), it has to go through vetting.

In the vetting process, an Electronic Target Folder “without minimally populated collateral damage considerations and intelligence gain/loss statements prior to vetting shall be considered incomplete and should not be vetted.” The Pentagon isn’t just about fighting wars, it’s interested in fighting them the right way, and that means checking to make sure the intelligence community, the government’s community of spooks and spies, think the target is valid, and that the commanders are planning for possible consequences from strikes or raids.

The specifics of the manual are a weird sort of niche material: the document is unclassified, so nothing inside it is regarded as a state secret, but it’s labeled For Official Use Only, a designation that signals it’s written entirely for an internal audience. And outside the Pentagon, the community of people who follow targeting rules is admittedly narrow.

Micah Zenko is one of those watchers. A senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, Zenko writes and researches on the norms of war, the ways expectations shape future behaviors of nations and militaries. In 2013, the Joint Staff released the Joint Targeting publication after Zenko filed a Freedom of Information Act.

“But it’s not just operational, there’s a moral element embedded in the instruction,” says Zenko, “including why certain laws of armed conflict apply and how they apply. It’s to get everybody on the same wavelength; the interesting thing from my perspective on it being public is it also describes the process now to the general public. Most American people won’t read this or know about it, but to the extent that it’s available to the general public, that makes a difference.”

The manual appeared online in full shortly after the election. While the rules for how the Pentagon picks targets might not be every voter’s first priority, it came up on the campaign trail. On Dec. 2, 2015, then-candidate Donald Trump said, “The other thing with the terrorists is you have to take out their families, when you get these terrorists, you have to take out their families. They care about their lives, don’t kid yourself. When they say they don’t care about their lives, you have to take out their families.”

That’s a violation that goes against the Geneva Conventions, and, in March, Senator Lindsey Graham alluded to Trump’s stance when he asked Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff John Dunford about the effect intentionally targeting civilians would have on the troops asked to do the targeting.

Dunford responded “those kind of activities that you’ve described, they’re inconsistent with the values of our nation and quite frankly I think it would have an adverse effect.”

Despite Dunford’s prior objections to the President-elect’s stated plans for the military, the Pentagon isn’t claiming responsibility for the release. When asked how the manual appeared online, a spokesman for the Joint Staff said the manual was prepared and reviewed for foreign disclosure release to Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, who are partners with the United States in Five Eyes, an intelligence-sharing alliance. The manual was posted on the joint electronic library, a .mil-access-only website. As for how it’s public? “The Joint Staff did not publically release,” said the spokesman.

It’s possible the target was an international audience, as preparation for sharing with Five Eyes partners suggests.

“The United States is the only great power who makes its military doctrine so widely available,” says Zenko. “The French don’t, the British do on some issues but not this, obviously the Chinese and the Russians don’t.” So it’s possible that the manual was prepared for release to specific allies of the United States, and then released to a larger audience as a way to try and shape standards across the militaries of the world.

There’s also the possibility that this release is aimed, not at setting rules for the future, but showing when existing practices have been violated. Civilian appointees to the Pentagon in this administration “use normative language about the use of force,” says Zenko, with an aim to “reinforce norms about precision, discrimination, proportionality, adherence to laws of armed conflict.”

“Then if there’s a rupture in that with the next administration,” Zenko continues, “it becomes more jarring, it becomes a little harder to sustain, especially among congressional overseers.”