On Thursday night, the news of President Donald Trump’s positive diagnosis of COVID-19 swept the internet.

Epidemiologists say that officials like Donald Trump, as well as First Lady Melania Trump and former Press Secretary Hope Hicks, both of whom also tested positive, are uniquely positioned to influence the pandemic because of how many people they come into contact with without taking many precautions.

“Certainly people like Hope Hicks and Donald Trump are ripe for being the index cases that can lead to super-spreading events, because they have really large networks and they are often amongst large crowds,” said Michael Mina, assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in a press call on Friday.

Trump was notorious for holding campaign rallies even before the pandemic, and has continued to host the events even amid the global pandemic. Several days before his COVID-19 diagnosis, the president held a Rose Garden event announcing his Supreme Court justice nominee, Amy Coney Barrett. Following the event, at least two attendees—Utah senator Mike Lee and University of Notre Dame President John Jenkins—tested positive.

That timing also lines up with a possible infection for Trump, epidemiologists say. But it wasn’t the only time the president was in a large crowd recently.

In the week or so before his diagnosis, Trump also held rallies in many states, including Pennsylvania , Florida, and Minnesota , and attended a debate in Ohio against democratic nominee and former Vice President Joe Biden on Tuesday.

Epidemiologists point out that Trump’s physical distance from other people, for security reasons, may help to reduce the number of people he possibly infected. But the president could still have been spreading the virus via aerosols while in close proximity to other political figures, like Biden. The incubation period for the virus can be up to 14 days, but most positives turn up within about seven days of coming into contact. Biden announced Friday that he and his wife had both tested negative, but Mina says “he’s not completely out of the woods yet.”

This amount of potential exposure to other people sets up a potentially enormous effort when it comes to contact tracing, which is a laborious process for normal people, much less for a presidential nominee who’s been traveling all over the country to meet with the public.

What is contact tracing?

Laura Breeher, an occupational medicine specialist at the Mayo Clinic, says contact tracing is a “fundamental public health practice.”

“It’s essentially the process of identifying those who may have had close contact with someone who was communicable with an infectious disease, and doing a risk assessment to guide appropriate action,” Breeher says.

With COVID-19, that action is often quarantining for 14 days from the last known contact with someone who was infected. That way, if the person does contract COVID-19 within that time period, they won’t spread the virus themselves. “It’s the process of stopping that chain of transmission,” Breeher says.

This means getting in touch by phone, email, or another means with any contacts who meet certain criteria. Contact tracing is implemented at the state level, though the CDC has guidelines for best practices. Anyone who was within six feet of an infected person for more than 15 cumulative minutes is considered potentially at-risk, and should be advised of their potential COVID-19 risk.

Importantly, the success of contact tracing depends on people remembering where they were, and with whom, in the days before they became infected. For her part, Breeher has begun to keep a journal, jotting down her daily activities and contacts as a precaution. She says keeping logs like this can help in the event someone gets a call from public health officials asking about exposure.

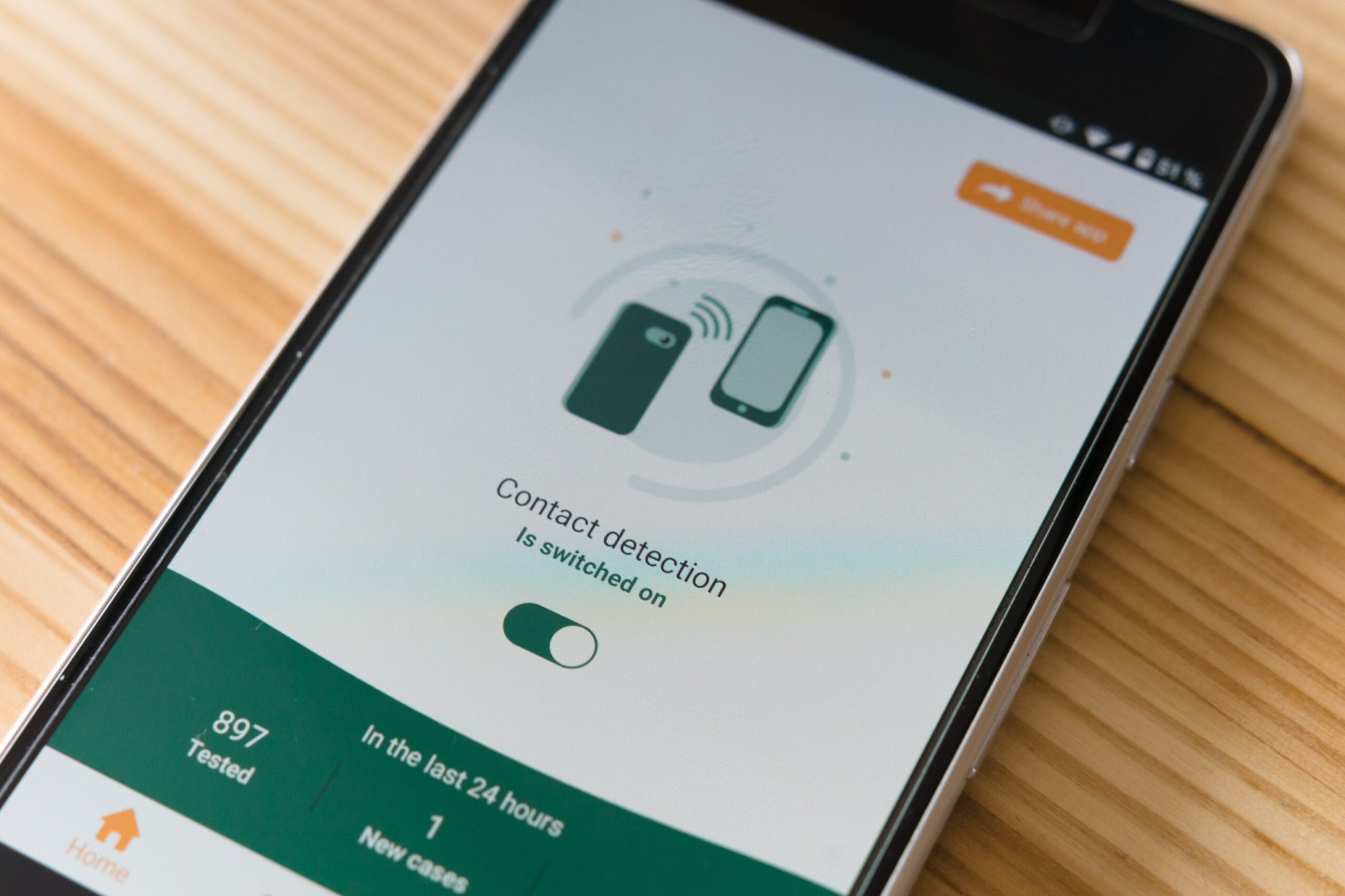

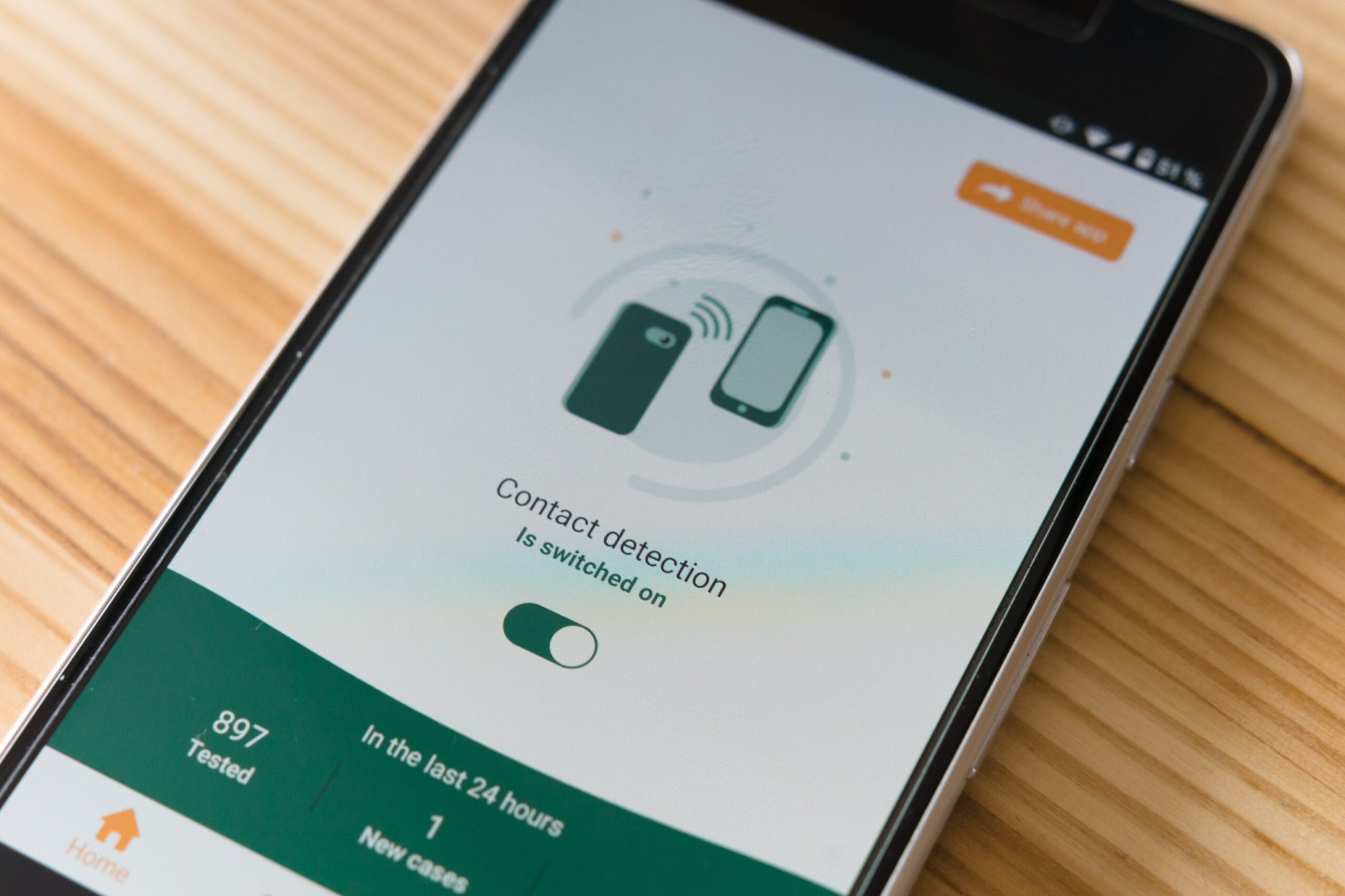

Some states, including California and New York, have developed contact tracing apps to streamline the process. These apps use phone data to identify people who were in the proximity of someone infected with the coronavirus, to help identify those potentially at risk, explains Thomas Russo, professor and chief of infectious disease at the University at Buffalo’s Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

“It is another tool in the toolbox that can facilitate public health officials, particularly when they’re overwhelmed, to try to do their job in the most efficient manner possible,” he says.

Ideally, Russo says, these apps are proactive, with as many people as possible downloading them. Users will receive push notifications if their cell phone data puts them in the close proximity of an infected person, alerting them to take the next steps, like getting tested and quarantining.

Apps may play a key role in wrangling the thousands of people who attended Trump’s recent rallies. In Pennsylvania, the state health department has asked anyone who attended the president’s September 26 rally in Harrisburg to download the state’s contact tracing app. “If you test positive, you can alert those you came in close contact with anonymously through the app,” officials said in a statement.

Tracing the president’s contacts

We don’t yet know how the president got sick with COVID-19. Finding that out would be a first step toward investigating when he, Melania Trump, and Hope Hicks were exposed, Harvard’s Michael Mina says—whether the point of contact was a supporter or White House official, for instance.

Since events like fundraisers and rallies are publicized and Trump is a public figure, in some ways, contact tracing is easier than it is for individual cases, Mina notes. “We don’t necessarily have to individually contact trace every person that was at a rally that might have been exposed, just for the sake of ticking boxes. This is the president — this is a very famous event.”

Local news outlets in places where rallies were held, for example, are in a position to notify residents and encourage them to get a coronavirus test or even quarantine for 14 days. “It can be done sort of in bulk,” Mina says.

So far, the president’s symptoms are reportedly mild , though late on Friday afternoon he was taken to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and will reportedly be staying there for several days. Going forward, Mina says the president’s diagnosis should be a “reality check” that these large public events are unnecessary and dangerous. “This should just drive home the message: The rallies should not be happening,” Mina says. “There is no reason to have an in-person rally right now.”

As for who’s responsible for limiting the risks of a rally, Mina says that responsibility falls primarily on officials. Attendees are “listening to Trump when he says it’s not dangerous. And by his rhetoric of saying it’s not dangerous, and saying ‘come to my rally,’ he is effectively single-handedly putting tens or hundreds of thousands of people at risk of getting this virus.”

“Frankly, I think if people die because of COVID that they get at his rally—to a certain extent, that’s on them for showing up and going—but it’s also on him,” Mina says. “He’s the president of our country, and people should be allowed to trust what he says.”