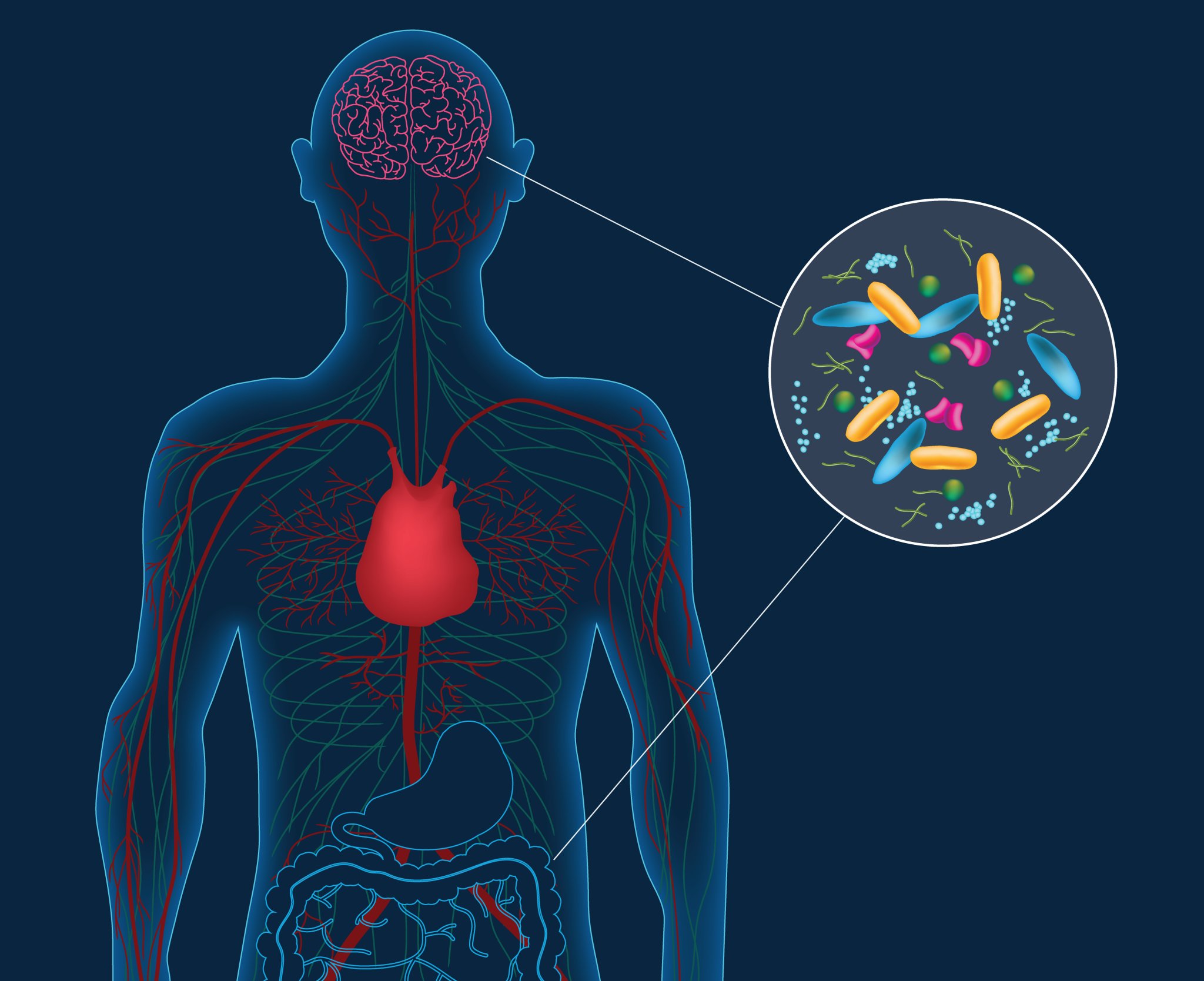

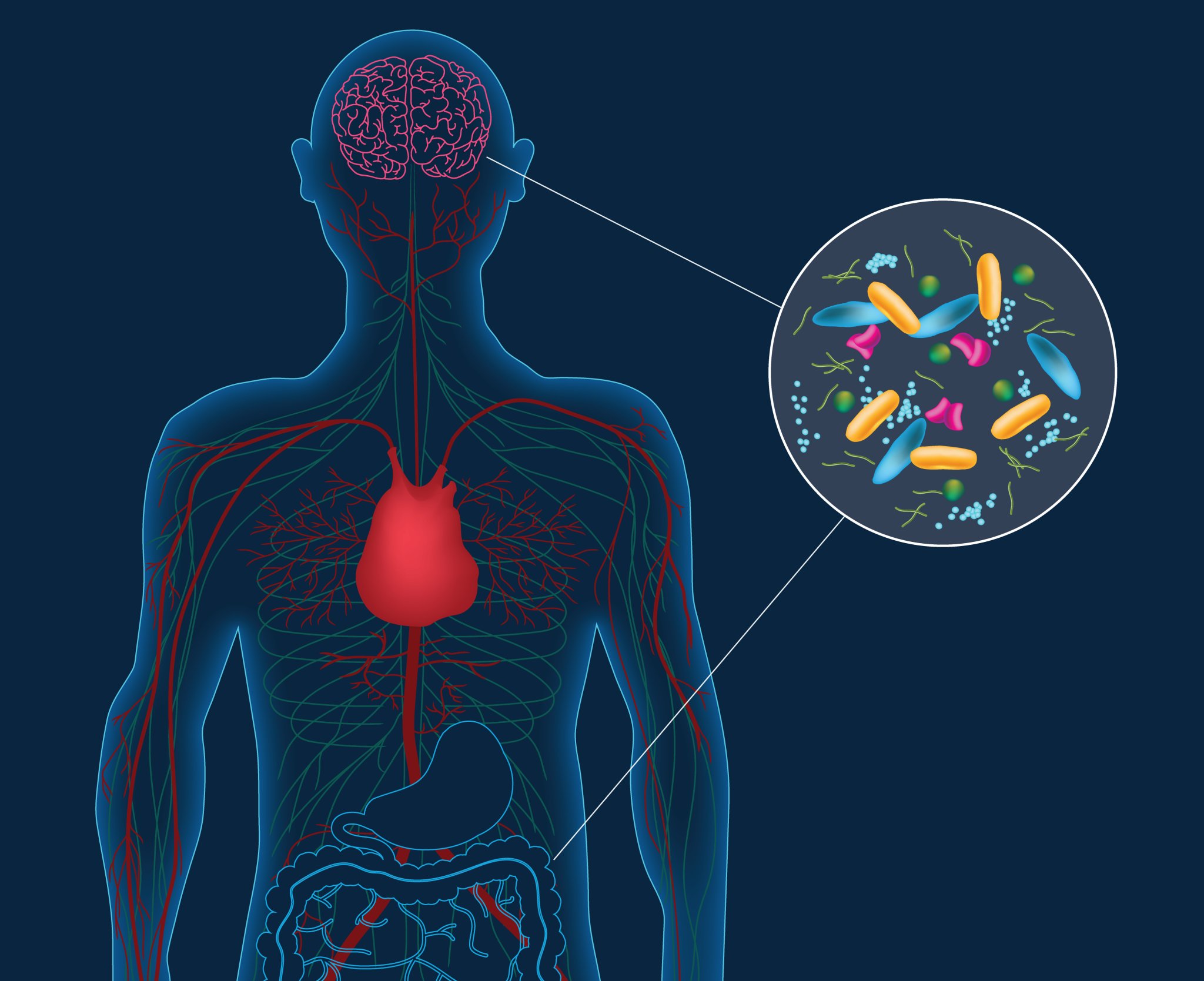

Many people with Parkinson’s disease also experience digestive symptoms (like constipation) for some time before their diagnosis. But until recently, research on the degenerative disease and how to treat it has focused on understanding how Parkinson’s works in the brain.

In a new study out this week in the journal Cell, researchers at Caltech found that changes in the type and number of microbes in a person’s gut may help determine whether they will go on to develop Parkinson’s. This new understanding of the disease could help researchers find better ways to treat it.

Previous studies on the gut microbiome—the collection of bacteria inside a person’s intestine—found that people with Parkinson’s disease had significantly different bacterial communities than those without the condition. But it was still unclear what microbes played a role in the illness and how. To figure this out, researchers took human gut microbes from both people with Parkinson’s disease and from healthy individuals, then transplanted them into mice being raised in a germ-free environment. These mice were also predisposed to over-express the human protein α-synuclein, which is what causes the plaque build-up characteristic of the degenerative disease.

The mice that received microbes from the Parkinson’s patients showed more loss of motor control (a common symptom of the disease) than the ones who got microbes from healthy people. This is the first time researchers have seen Parkinson’s worsened in mice by way of associated gut microbes. While scientists still aren’t certain exactly which microbes associated with Parkinson’s are actually tied to these symptoms – or how that connection might work – the study adds evidence that bacteria do play a role.

“This study is really a stand out in microbiome research,” says Justin Sonnenburg, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford Medical School who wasn’t involved in the new study. The experiments, he says, clearly show that microbes could play a causal role in Parkinson’s disease, at least in a mouse model.

But that’s an important distinction, Sonnenburg cautions. As is the case in all mice studies, these results might not translate to human health. And even if human patients are similarly effected by these microbes, we still have no idea how the connection works. There may be other crucial components of the disease left for scientists to uncover.

In the future, researchers plan to analyze the gut microbiomes of people with Parkinson’s to figure out which microbes could be involved. If they can be identified – and if these microbes are truly as integral to the disease as this study suggests – then perhaps targeted probiotics or dietary changes could one day help to treat or prevent the disease.