Today, hundreds of scientists are gathered in Washington, D.C. for the international summit on genome editing. The three-day conference will discuss the ethical and appropriate use of all genome-editing technologies, but it will likely pay close attention to the newest and arguably easiest method, CRISPR-Cas9, known colloquially as just CRISPR.

The technology has been at the center of scientists’ minds worldwide since April, when Chinese researchers reported that they used the tool to edit nonviable human embryos, or ones that have no chance of developing into human beings. The summit, which started early this morning, is sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, as well as the Royal Academy, and will include researchers from the United States, Great Britain, and China as well as representatives from at least 20 countries worldwide.

The group plans to discuss many direct applications of the CRISPR technique, including the ability to perform genome editing both on human embryos to treat a specific disease as well as to implement gene drive, which would introduce new genes into a few organisms that would then pass that change on to future generations.

Why is this conference so important?

Currently, the rules regarding the use of genome editing tools are hard to follow and as Nature reported back in October, vary by country. In the United States, researchers cannot use federal funds to employ genome editing on embryos and using it in clinical development requires approval, however there are no direct bans on its use.

On the other hand, the United Kingdom allows human-genome editing for research if approved by their version of the FDA (the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority) but it directly bans its use in clinical development. Other countries, such as China, India, and Japan, have guidelines that restrict editing the human genome, but they are completely unenforced.

This conference is also the first of its kind and could therefore guide how future research using CRISPR and other gene editing tools will unfold.

Why this controversy now?

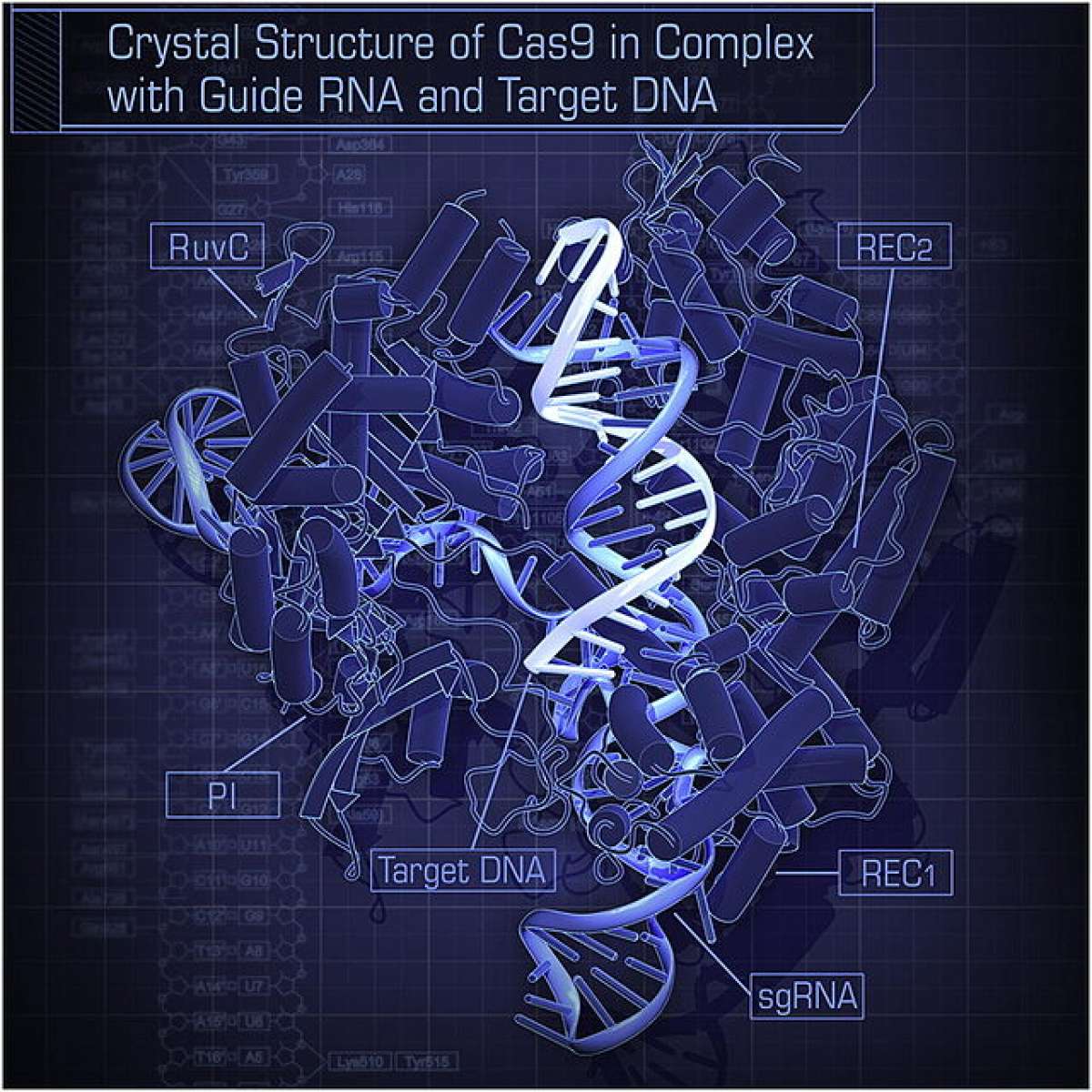

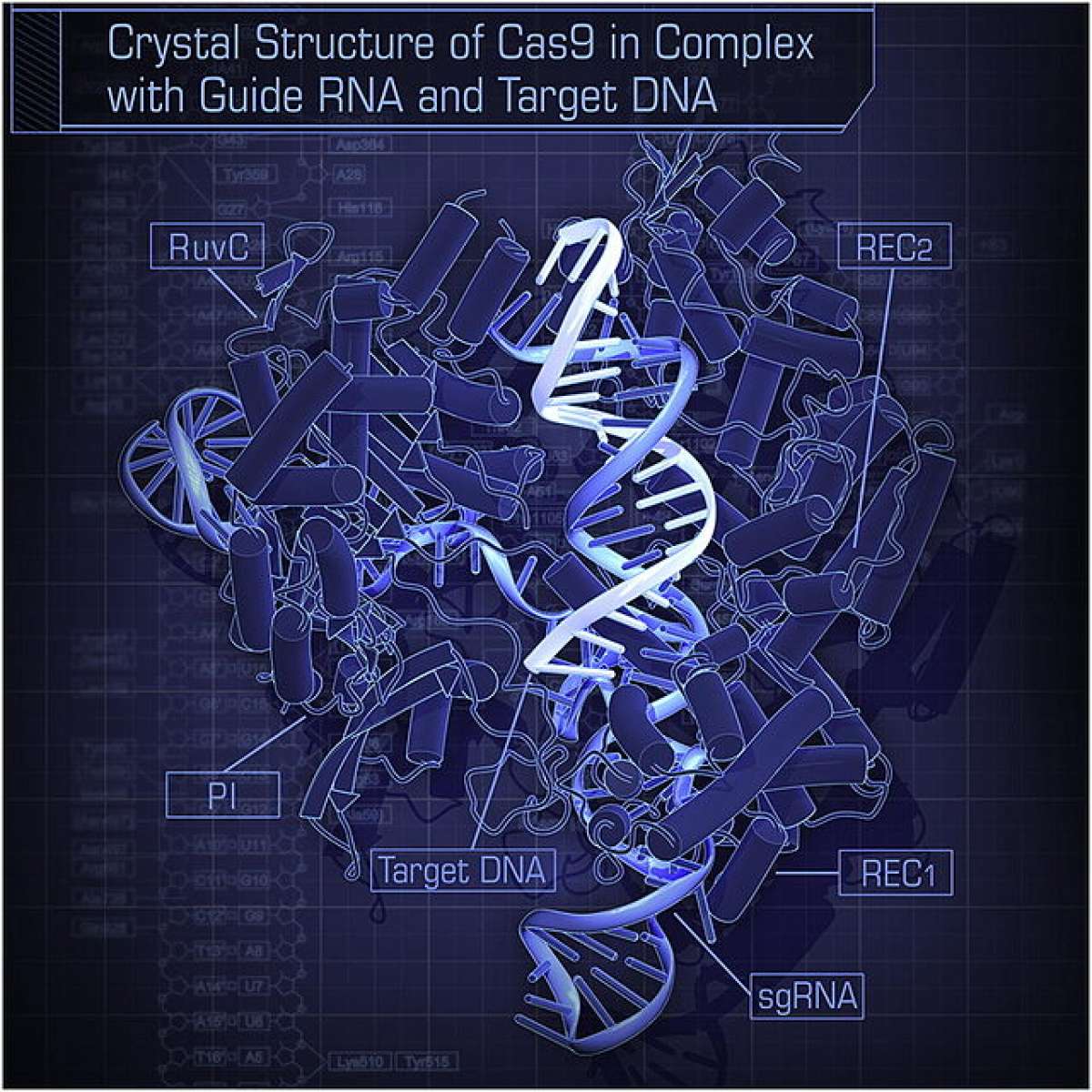

CRISPR is not the first genome-editing technique; others, such as zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) technology and another enzyme binding technique called TALENS have been around for years. However, as many researchers have pointed out, the CRISPR technique is simple, highly specific, and versatile—more so than any other tool before it. CRISPR has the potential to allow scientists to change the DNA in a viable embryo. This change would then be passed on to that individual’s children and would continue to future generations. In this way, the editing technique could allow humans now to alter or direct the course of future generations, an ability many researchers—including Francis Collins, the director of the NIH, in an interview with Stat—say we are not ready and don’t have the foresight to employ.

What will the summit provide?

Many researchers have already publically stated where they stand on the use of gene-editing techniques. But this summit could likely provide a regulatory approach to help researchers around the world—as a team—navigate how they will use the CRISPR technique over the next several years and decades in an effort to regulate, but not limit, scientists abilities to use this technique for the greatest medical need. However, since various countries already have some rules in place guiding gene-editing research, it remains to be seen what impact any agreement at the summit would have on the field.

Stay tuned to Popular Science for more updates about the summit, which is scheduled to run from Dec 1-3.