The moon gets all the attention come Halloween, but this season the sun is giving us a scare—or rather, a flare.

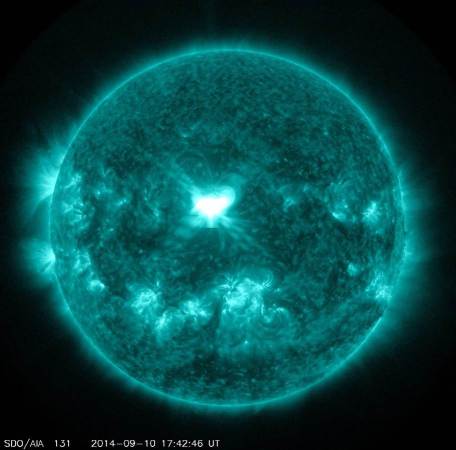

On Thursday, a solar flare was recorded at its peak by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory at 11:35 a.m. Eastern Time. The burst of energy caused a coronal mass ejection (CME), which is essentially a giant magnetic field fart. The light and particles from the CME will reach Earth this Sunday as a solar storm, but won’t physically affect humans or wildlife.

The space agency classified this flare as an X1, which is particularly raucous; the rating system runs from A, B, C, M, and X in terms of weakest to stronger, with numbers on top to show even more power. NASA once clocked an X28 in 2003. This is also the first X-class flare of the new solar cycle, says Kathy Reeves, an astrophysicist with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. A solar cycle is the 11-year period during which the sun’s north and south poles flip, affecting its magnetic field and solar activity.

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory caught images of the flare and CME over multiple days this week. The particles looked like snow as they hit the detector, says Reeves.

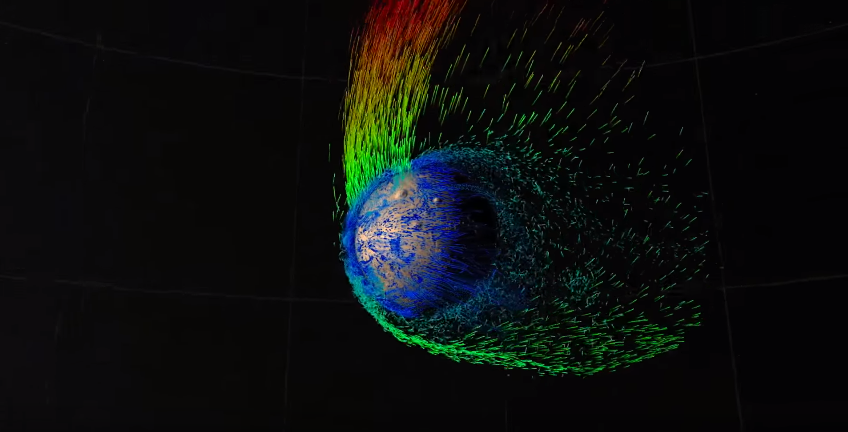

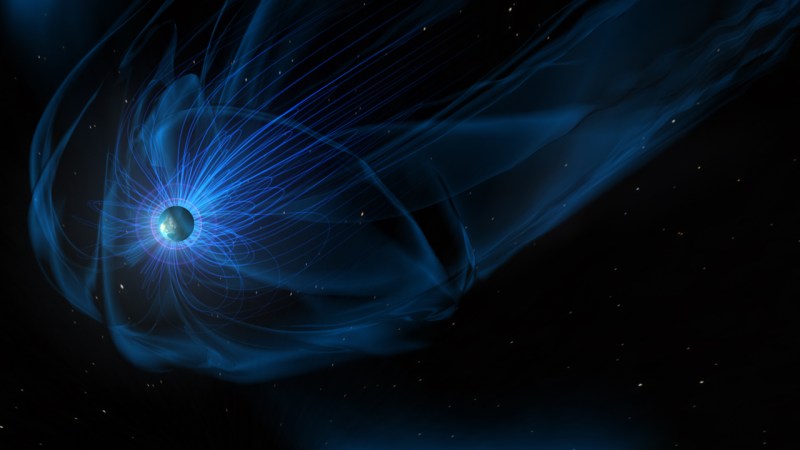

Though solar flares and CMEs often correlate with one another and can occur simultaneously, they’re different phenomena. Both are caused by changes in the sun’s magnetic field that radiate out from its core. As the field ripples and realigns, it releases tremendous energy. This event can cause a great flash that scatters light: the solar flare. It can also hurl matter into space: the CME. The CME projects a swarm of magnetized particles out from a single spot on the sun’s surface. This cloud is known as “plasma.”

[Related: What happens when the sun burns out?]

Certain solar flares can interfere with radio communications. Sometimes airlines will divert flights set to travel over the Earth’s poles, because the sun’s electrons and energetic protons tend to amass near them and can disrupt the flight’s radio.

Solar flares can also make the Northern Lights go a little haywire, which could create a “spooky effect” this weekend, according to Reeves. “So you can see Northern Lights a little further South on Halloween,” she says. “That might be cool.”

![NASA Set To Launch New Solar Satellite IRIS [Updated]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/S6GKCDYKQ7UG47MAKV5DVVUWB4.jpg?w=735)