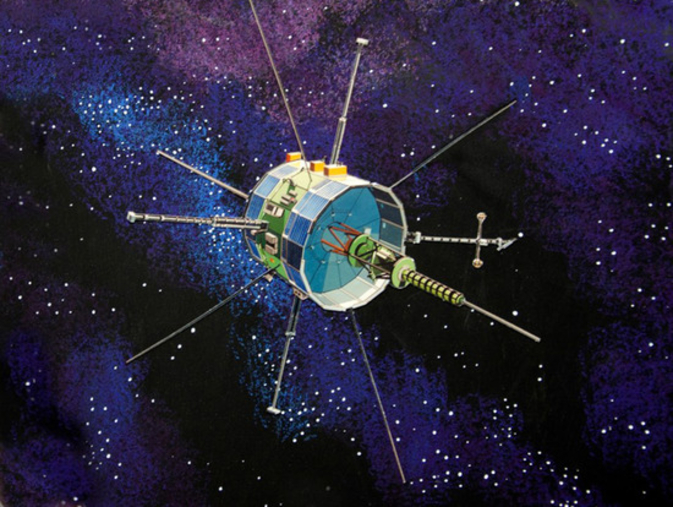

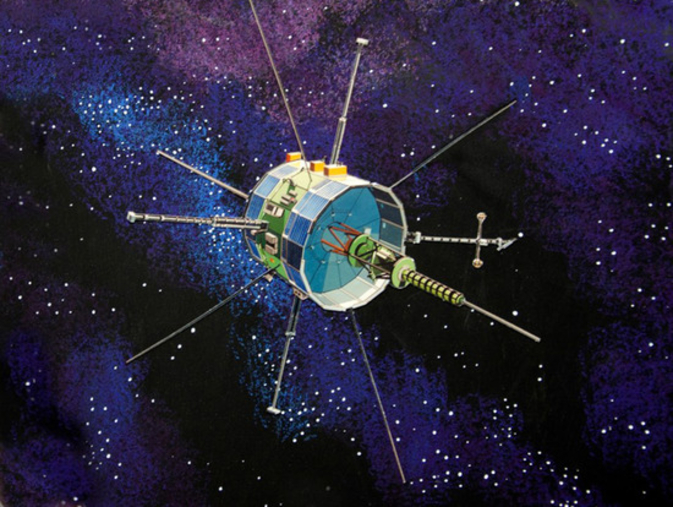

This coming August, the California-based private company Skycorp will attempt to contact and possibly regain control over NASA’s International Sun-Earth Explorer-3 satellite, a spacecraft NASA has no plans to reuse. That’s because the space agency has already repurposed ISEE-3, which launched on August 12, 1978, multiple times, stretching its useful lifetime more than anyone anticipated. So this upcoming attempt to give it another lease on life is really just another phase in the small satellite’s long and exciting life story.

ISEE-3 was the third in a series of satellites, preceded by its companions ISEE-1 and ISEE-2. The three satellites’ joint missions was four-fold: to investigate the solar-terrestrial relationship at the edge of the Earth’s magnetosphere, to examine the interaction between the Solar wind and the Earth’s magnetosphere, to gather data and experience working within plasma sheets, and to investigate the effects of Solar rays and flares around the Earth’s orbital plane (1 astronomical unit or AU from the Sun). To this end, the three spacecraft were fitted with complementary instruments designed to measure plasmas, energetic particles, waves, and fields.

ISEE-1 and ISEE-2, built by NASA and ESA respectively, launched on October 22, 1977 into a highly eccentric geocentric orbit with an apogee of 23 Earth radii. There they established a moderate separation from one another and carried out simultaneous coordinated measurements of the Solar wind, the bow shock, and the magnetosphere. Neither was built for longevity; both ISEE 1 and ISEE 2 re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere on September 26, 1987.

ISEE-3 has a more interesting story since it neither went into orbit nor reenter the atmosphere. On November 20, 1978, the nearly 900-pound ISEE-3 became the first satellite to be successfully placed at the Lagrangian libration point 1 L1, a point 932,056 miles from the Earth towards the Sun where the Earth’s gravity counterbalances solar gravity. At that point, any spacecraft will orbit the Sun in one Earth year while a natural body by comparison would have a much shorter orbital period.

From its L1 vantage point, ISEE-3 carried out its primary mission until 1981. In 1982, it was given a second chance at life.

Because it wasn’t in a position to return to Earth, scientists from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center took advantage of a healthy spacecraft and sought to repurpose it, turning the mission into a cometary one. spacecraft. The new mission, which would send ISEE-3 through Earth’s magnetic tail on a path to intercept a comet, began on June 10, 1982 with the spacecraft thrusters coming back to life.

On its second life, ISEE-3 completed the first deep survey of Earth’s magnetic tail, detected a large plasmoid of electrified gas ejected from Earth’s magnetosphere, and made five complex flybys of the Moon. Then it was sent on a trajectory to fly by Comet Giacobini-Zinner. The new target came with a name change; ISEE-3 became ICE, the International Cometary Explorer.

On September 11, 1985, ICE passed within 4,885 miles of the comet’s core, making it the first spacecraft to ever fly past a comet. The data it gathered on this pass confirmed that comets are “dirty snowballs” that shed surface material as they tear through space. ICE intercepted a second comet a year later on March 28, 1986, flying 25 million miles from the sunward side of Halley’s Comet where it gathered upstream solar wind data.

ISEE-3-turned-ICE was repurposed a third time in 1991. This time, it became a dedicated heliospheric mission, redirected to investigate gamma rays and coronal mass ejections in coordination with ground-based observations. But the end was on the horizon. By 1995, ISEE-3/ICE was being operated on a low duty cycle. NASA finally terminated operations on May 5, 1997. It’s been in a heliocentric orbit at about 1 AU ever since.

Now, after more than 15 years of inactivity, ISEE-3/ICE might be getting another lease on life. The spacecraft will pass by the Earth this coming August, giving Skycorp the perfect opportunity to establish contact. If communications with the spacecraft are successful, great. If not, it will swing by the Moon and continue on into a heliocentric orbit. In either case, it’s one of the more interesting citizen science programs out there, and a really interesting attempt to bring a piece of history back to life.