A fossilized skull discovered in Ethiopia in the 1970s should be considered an entirely new species of human, scientists proposed this week in an effort to shed light on the very murky question of what to call our ancient ancestors.

In a study published on Thursday in Evolutionary Anthropology Issues News and Reviews, researchers compared anatomical traits in fossil hominins—the group that includes present-day humans and our extinct close relatives—from Africa, Europe, and Asia. They concluded that two currently recognized species should be retired, and that the 600,000-year-old remains from Ethiopia, along with several other specimens, should be classified as a new species they’ve dubbed Homo bodoensis.

Not everyone is convinced that a new species name is needed—after all, none of these specimens represent lineages that have never been studied before. However, the researchers argue, the changes could help researchers decipher a murky period in human evolution and move past terms with vague meanings and racist legacies.

[Related: Your ancestors might have been Martians]

“We’re becoming increasingly aware that these groups did move and did interact, and that’s why it’s important to have a proper way of talking about them,” says Mirjana Roksandic, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Winnipeg in Manitoba and coauthor of the paper. “It really opens the possibility to talk about who moved when, and what happened to them when they moved, and who actually interacted with whom.”

She and her colleagues focused on hominins who lived during the Middle Pleistocene age, which spanned from 774,000 to 129,000 years ago. Although paleoanthropologists refer to these hominins as different species, they’re not using the term as most of us normally think of it. “They interacted, they interbred, and they cannot be considered as definite biological species,” Roksandic explains. Instead, the category is used to describe groups of hominins with very similar anatomical features.

These differences are more obvious in some groups of hominins than others. European Neanderthal fossils from this period differ in numerous ways from modern humans, Roksandic says. However, many other hominin fossils look very similar, making it harder to determine how they relate to each other and to Homo sapiens.

In the past, new species were often declared on the basis of a few teeth or other fragmentary evidence, says John Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved in the new research. One such case was Homo heidelbergensis, which was first named after a jawbone found in a gravel pit in Germany in the early 20th century, he says.

Then, in later decades, many fossils that didn’t seem to fit with Neanderthals, modern humans, or our ancestor Homo erectus were lumped in with Homo heidelbergensis. “The species was named after a mandible; we never knew what the head and face should look like,” says Shara Bailey, a biological anthropologist and director of the Center for the Study of Human Origins at New York University. “Basically it’s like a trash basket category.”

This helped spawn a “totally confusing” situation, Roksandic says, in which the name Homo heidelbergensis is sometimes used to refer generally to hominins from the Middle Pleistocene, and other times to refer to various specimens found in Europe. She and her colleagues argue that it’s time to abandon the name altogether, given that recent genetic evidence suggests that many fossils currently assigned to Homo heidelbergensis are actually early Neanderthals.

Then there’s Homo rhodesiensis, which was first known from a skull uncovered by mining activity in Zambia in the 1920s. The term is sometimes used to indicate a common ancestor of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, but can also refer to all the hominin lineages represented in the Late Pleistocene. But the name is rarely used in either context, because of its association with the atrocities committed under British colonial rule in the region of Rhodesia (now Zambia and Zimbabwe). For these reasons, Roksandic’s team writes in the new study, Homo rhodesiensis has to go.

[Related: Humans owe our evolutionary success to friendship]

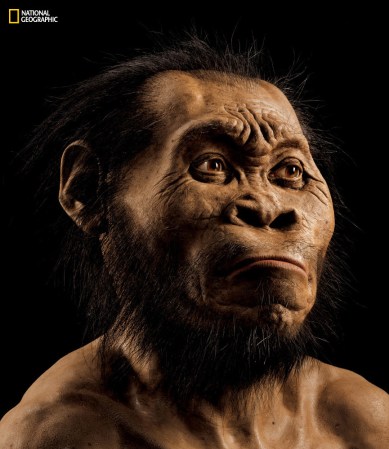

“Homo bodoensis would fill that void that’s left by Homo rhodesiensis,” she says. The researchers selected the enigmatic skull from Ethiopia to represent the species in their description. However, they also consider the Zambian skull and several other sets of fossils from Africa, and possibly the eastern Mediterranean, as members of Homo bodoensis.

Like Neanderthals and some Asian hominins from the Middle Pleistocene, Homo bodoensis seems to have had an enlarged brain—a crucial development on the road to modern humans. It’s likely that Homo bodoensis was the first to split off from their shared common ancestor, with the remaining branch later splintering into Neanderthals and a group called Denisovans found in Asia, the researchers propose.

Homo bodoensis’s most distinctive feature is a three-part segmented brow ridge. There’s no obvious advantage to having different kinds of brow shapes, but this region does vary among different kinds of hominins, Roksandic says. Neanderthals had thick, curved brow ridges, while in modern humans the brow is less pronounced and the sides are thinned out.

As a next step, she and her colleagues are planning to investigate whether fossils from Europe and Asia might be members of Homo bodoensis, which could shed light on whether and when the group might have moved out of Africa.

“It’s really hard to understand what is happening in terms of human evolution in that time period unless you look at it on a very global scale,” Roksandic says.

What’s in a name?

Hawks agrees that the two species that Roksandic and her colleagues propose jettisoning are “a problem.”

“These are confusing names, they have bad histories, and it would be way better if we had names that actually could be [scientifically] tested and that can apply in a sense that all of us are willing to use,” he says.

However, he favors a different solution. “All of these populations interbred with each other, and it seems like they’re the same species—and the name for that species is Homo sapiens,” Hawks says. “Why don’t we recognize that they’re the same species, and all these fossils going back to the common ancestor are representatives of that evolving species?”

Bailey also isn’t sure that Homo bodoensis brings clarity to this phase of human evolution. Given that the fossils seem to belong to a direct ancestor to Homo sapiens, she says, “Why don’t we just call that archaic Homo sapiens?”

Nonetheless, Bailey says, the paper makes a good case for ditching Homo heidelbergensis and Homo rhodesiensis. “It also provides readers with kind of a glimpse into just how complex human evolution is, that it’s not this ladder-like [process in which] we evolved step-by-step into ‘Tada, we’re Homo sapiens!’”

The names we give bygone hominins reveal how we see them fitting into our family tree—and what makes the humans alive today unique. “That’s what people care about: what’s ‘us,’ when did we evolve, when did we develop the things we associate as being special about us?” Bailey says.

Names allow us to understand the relationships between different hominin lineages and how they interacted, Hawks says, but they needn’t be set in stone.

“It’s good to have these conversations,” he says. “Looking at the way that we describe groups, it’s really important to continue to have critical thinking about what are we accomplishing by naming them?”