About 240 miles southeast of Kyiv, Ukraine, the city of Dnipro is known for being a hub of high-quality missiles and world-renown defense industries. But during the height of the Soviet Union, Dnipro was also called the “Rocket City.”

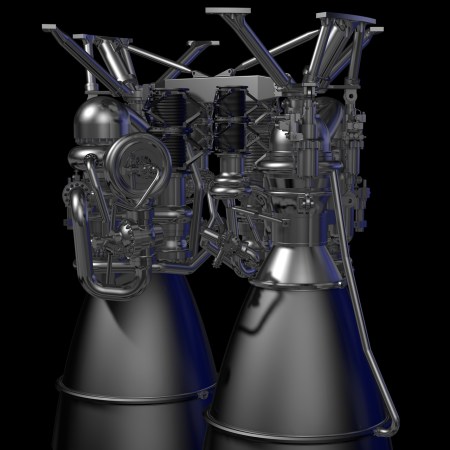

Dnipro, the fourth largest city in the Ukraine, still currently holds one of the largest spacecraft production facilities in the world. The major manufacturing center has built everything from rocket engines to rendezvous docking systems for spacecraft. Throughout history, the industrial city helped firmly position Ukraine in the global space sector—and even became one of the most valuable assets the Soviet Union had in the Cold War, says Asif Siddiqi, a professor of history at Fordham University who has written extensively on the Soviet space program.

“Ukraine was a very important player in the Soviet space program, because a lot of their space assets and space industry was based in Ukraine,” says Siddiqi. “And a lot of the key leading engineers and scientists were of Ukrainian origin.”

But now, Ukraine’s decades-long presence in the space sector has been interrupted by Russia’s invasion. The war has had catastrophic impacts on the whole country—and the rocket and satellite industries aren’t exempt. With the conflict intensifying at a pivotal point in the country’s effort to bring its space program back to the heights it had seen during the Cold War, the future of the agency is uncertain.

[Related: How Sputnik shocked the world and started the space race]

During the 1960s, Ukraine was heavily involved in the race to the moon. By the time NASA’s lunar landing effectively ended the space race in 1969, Dnipro and Ukraine had established a foundation for building future space exploration technologies. The country set its sights on creating Earth-orbiting space stations—a move that would thrust Ukraine, and many of its early experts, onto the global stage.

“By the end of the Cold War, they had quite a lot of experience in operating pretty modest space stations in Earth orbit,” says Siddiqi. “And that’s what laid the foundation for what would later become the International Space Station.”

After the Soviet Union fell in 1991 and Ukraine declared its independence, Russia and Ukraine were still some of the biggest players in the space race arena. Although Russia retained most of the space assets from the partnership, Ukraine did succeed in parting with a good amount of its resources. In 1992, the State Space Agency of Ukraine was established by the government to organize and direct the country’s future space policy and exploration programs.

Until now, Siddiqi said there had always been a “kind of understanding between the two countries in terms of space cooperation.” But since Dnipro’s massive manufacturing boom in the 1960s, the country’s presence in space missions is much different today. In the past few decades, Ukraine’s rocket industry has been on the decline.

The last time the country had a craft in orbit was in 2011, when it launched the satellite Sich-2 from a Russian spaceport. That satellite stayed active for about a year into its expected five-year mission before Ukraine’s space agency lost communication.

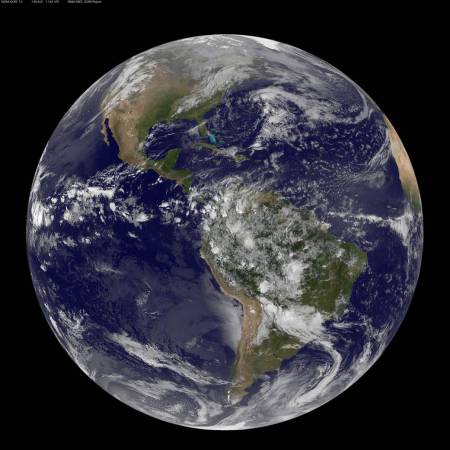

But the agency is trying to make a resurgence. Earlier this year, SpaceX launched the Earth observation satellite, Sich 2-30—the first Ukrainian satellite in 10 years. On the social messaging platform Telegram in January, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky stated in a post that the Ukrainian engineers and specialists who made the successful launch possible “proved their ability to create new models of modern space technology and establish Ukraine as a powerful space power.”

The satellite was designed to take digital images of the planet, and collect data for the military and Ukraine’s space agency over the next five years. The intel will be used to monitor agricultural use, water resources, natural disasters, and security and defense issues. While it’s unknown whether the satellite is currently being used to locate or combat Russian forces, Ukraine has been seeking satellite data from other firms and space agencies, the BBC reports.

Just as Ukraine was jumping back into the saddle, Russia’s invasion may have put a pin in any short-term progress. Dnipro, a city renowned for its past defense enterprises, has been thrust into wartime. As Russian forces move closer towards the outskirts of Kyiv, many Ukrainians are choosing to flee there. At the time of this article, the status of operations and State Space Agency of Ukraine’s website were not accessible.

[Related: Russian forces just captured Chernobyl. What are the radioactive risks?]

Ukraine, however, still has ambitions of expanding its role in space exploration, specifically alongside NASA’s plans to go back to the moon. In 2020, the country became the 9th to sign the Artemis Accords, an international agreement to establish rules that encourage and guide civil lunar exploration. More notably, it’s a document Russia and China have refused to sign, with some experts citing that the accord is too “US-centric.”

Although Ukraine’s aerospace industry has ongoing space collaborations with many Western countries, it’s too early to tell whether their program will get the support it needs. In contrast, Siddiqi says Russia’s own space program could become an “international pariah” among prominent actors after choosing to invade Ukraine.

Yet Ukraine’s space program was already planning on moving out from under the superpower.

In a August 2021 announcement of a rocket launch scheduled for later this year, Head of the State Space Agency of Ukraine, Volodymyr Taftai, told the Defense Express that: “For Ukraine, such work is of great importance because in this case we are talking about the actual revival of full-fledged rocket and missile technology in Ukraine and the return to the club of space countries of the world without the participation of Russia.”

Russia’s latest move may be the final push the Ukranian space agency needed to break its ties. However, Siddiqi says such a disentanglement from its relationship with Russia won’t be easy for Ukraine—or the rest of the world.

“Whatever happens with this war, whatever comes out of it, I think it’s gonna take a while to assess,” says Siddiqi. “My guess is the Ukrainian government will have other priorities beyond space in the short term.”