On October 9, 2006, North Korea conducted its first nuclear test. Since then, the nation has tested nuclear devices four more times, most recently in September 2016. Running parallel and complementary to the nuclear program is a missile program that, twice in July, tested ICBMs with a range that can likely reach most of the continental United States. Earlier this week, a report from the Defense Intelligence Agency estimated that North Korea has miniaturized a nuclear warhead, making it small enough to fit on a missile.

In addition, the estimate from the DIA says North Korea has up to 60 warheads, a number on the upper end of most independent estimates. More efficient weapon design might help with this process, stretching limited fissile material into a greater arsenal. We spoke to researchers to see what they could glean from publicly available information about the state of North Korea’s nuclear program, and how it compares with other countries’ nuclear histories.

‘The Disco Ball’

“I think our best indication in this case with North Korea is to take them at their word, and they’ve been quite clear in their own statements that they are looking for a miniaturized device,” says Catherine Dill, a senior research associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. “If you think about the Kim Jong-un visit in March 2016, when he stood next to what appeared to be miniaturized warhead, I think that’s a pretty clear indication.”

In that March visit, Kim Jong-un stood next to what the research community dubbed “the disco ball,” a faceted silver sphere. From that photograph, researchers were able to figure out some details of the warhead.

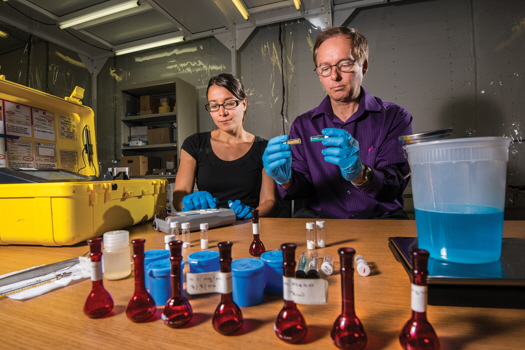

“We can take measurements of that silver orb, and we can say it fits in the whole range of their missiles, and we can make estimates on its weight, based on what we know about real warheads,,” says Melissa Hanham, also a senior research associate at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, “but unless they show us the inside of it, or they explode it on the tip of a missile, there is no offer of proof.”

The tunnels

One reason it is so hard to determine the nature of North Korea’s weapons is because of how the country tests its warheads. The United States tested its nuclear weapons in places like New Mexico (later Nevada) and above Pacific islands, and the Soviet Union, too, used a site deep inside what is now Kazakhstan (and what was then part of the U.S.S.R). These test sites, while harmful to people in the proximity, had the virtue of not antagonizing other superpowers (or at least, not any more than nuclear testing already increased tensions). North Korea’s test site is less than 50 miles from the border with China, and all North Korean nuclear tests so far have occurred in tunnels, dug underneath a mountain. One risk of testing a bomb under the mountain is that, if the bomb is too powerful, it could blast open part of the mountain and expel those radioactive gases.

“With other countries in the past,” says Dill, “the composition of the warhead becomes known with the atmospheric information from the test.”

But those gasses could become a major problem for Kim Jong-un, antagonizing a China already skeptical of the nuclear program.

“The North Koreans have gone out of their way to give assurances that they know what they are doing and are not going to release radioactive clouds over Northeast Asia,” says Joshua Pollack, a senior research associate at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. This means that the mountain, and the North Korean regime’s ability to dig tunnels under it, might set a hard limit for how powerful a weapon the country can test without risking the release of gas.

“My colleagues and others have independently done some modeling of the mountain and reached the conclusion that with their current approach of horizontal tunnels they can actually test a 300 kiloton device without having to resort to digging down,” says Pollack, “so it is possible that a moderate-size H-bomb could be tested there. They also don’t have to test an H-bomb at full power to know if it works. They have enough space to do something if they’re so inclined, but they’ve never done anything that big before.”

The H-Bomb

The simplest way to make an atomic bomb is to build a fission weapon, where a large atom is split into smaller atoms, releasing a devastating amount of energy. The weapons dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were both fission weapons, with destructive force equal to 15 and 21 kilotons of TNT, respectively. So far, four of North Korea’s five nuclear tests produced explosions estimated below this range, with the September 9, 2016 test an outlier estimated to be between 20 and 30 kilotons.

An H-bomb, also known as a thermonuclear warhead, instead uses fusion to create a blast that is at least an order of magnitude more powerful than an atom bomb using the same amount of fissile material. The United States first tested an H-bomb in 1952, seven years after the first test of the atom bomb. The Soviet Union first tested an atomic bomb in 1949; it then tested a working thermonuclear design in 1953. Both of these countries were superpowers, putting vast resources into weapons programs. For a better comparison, it helps to look at countries that developed nuclear programs without massive economic engines behind them.

“If you think about the first test in 2006, over 10 years ago that seems to be congruent with the developmental milestones of other states,” says Dill, “And it’s more impressive in fact if you factor in the sanctions regime that has been in place over North Korea for the last 10-15 years. I think so that what is interesting is that some people will say they haven’t conducted tests for an H-bomb, and again, I think if we look at testing versus other countries, and I think China is probably the best comparison in this case. With a minimum number of tests, it’s possible to make some very significant physical details that could lead to the development of an H-bomb.”

China’s sixth nuclear test, it turns out, was a thermonuclear test, and that’s right where estimates place North Korea’s development.

“There are people who have been persistently skeptical of North Korea given all the clear evidence of poverty there, which I think is a mistake, analytically,” says Pollack, “China was dirt poor, India was dirt poor when they tested their first bombs. What’s the big surprise? Just because there’s not a lot of light at night in satellite photographs of the country? I don’t understand why that should make us doubt that they’re capable of doing this. That speaks more to their priorities as a regime than it does to what the country is capable of doing.”

While the first nuclear programs had to discover the science as they went, the fundamentals of how nuclear weapons and missiles work remains consistent, and while it’s been a long road from when North Korea first announced its nuclear ambitions, once the program was under way, there is little reason, given the available, open-source evidence to doubt that the country is in fact capable of making the weapons it set out to make.

“The technology, regardless of whether it’s nuclear or its missile, is around the 50s-60s,” says Hanham. “North Korea doesn’t have a lot of resources but it is disproportionately sinking its resources into doing this. It should not be surprising that North Korea can accomplish these things in 2017 after they’ve been telling us they want to, and they’ve been marshaling enormous resources into doing these programs.”

The Crisis?

Given this build up, on a prescribed path and towards a declared end, is there a reason the present moment feels particularly fraught?

“The events we’ve seen for the past few months that have for some reason seemed to contribute to perception of the crisis,” says Dill, “are part of technological milestones that North Korea has been working on for many years, and more importantly they have been talking about for many years. It is a serious program, they clearly have the technical capabilities, and we are beyond the point where it can be ignored or understated.”

There is another way for Kim Jong-un to convey the serious nature and technological progress of the North Korean nuclear program, but it’s an option that no one is particularly eager to see.

“The alternative,” says Hanham, is “to have a live nuclear test, and that is very dangerous because it can be interpreted as an act of war.”

![Who’s More Powerful, China Or The United States? [Infographic]](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/LCXTUHTBMLHVHTLMOOHVKQJGQA.jpg?w=525)