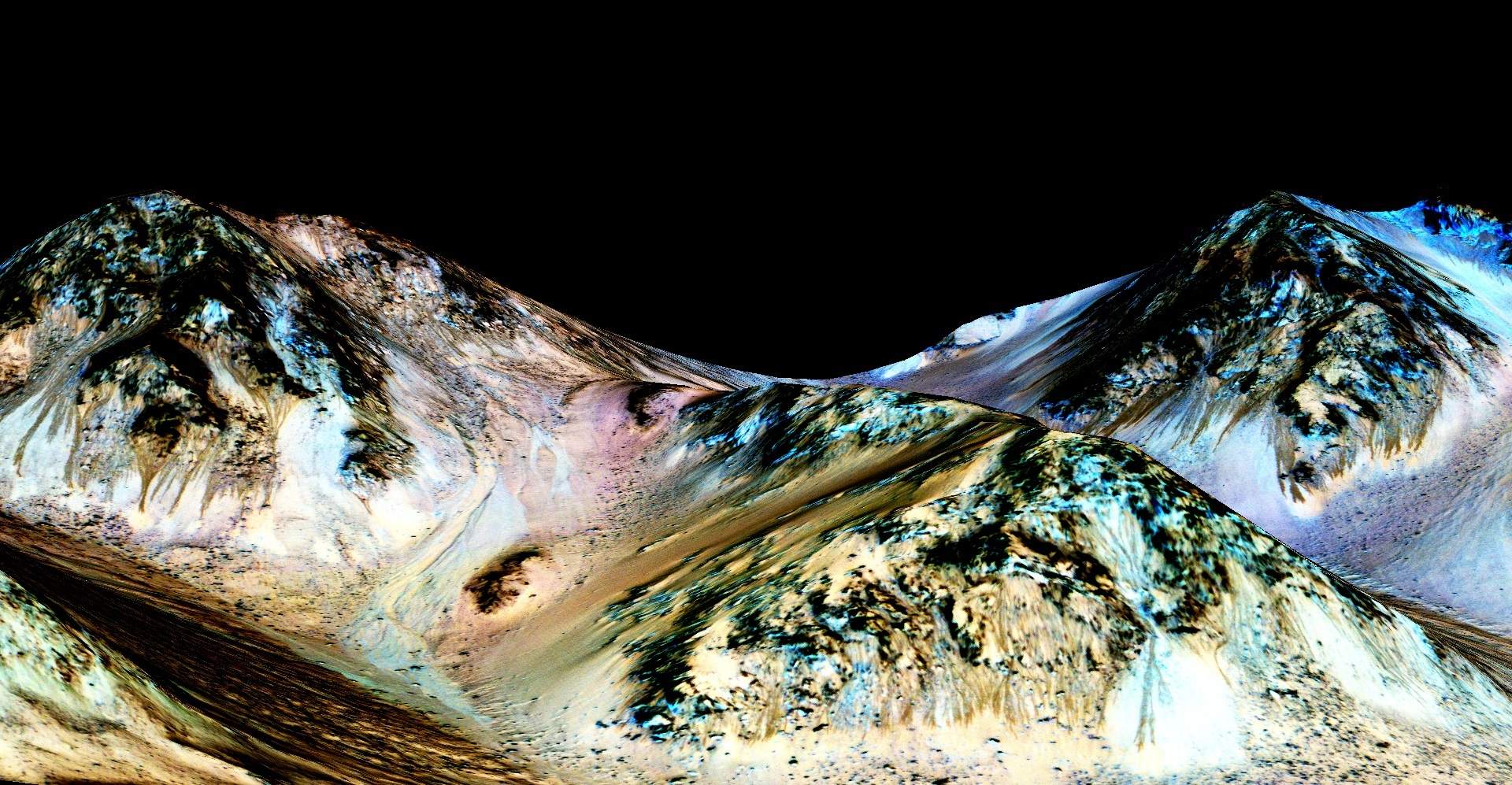

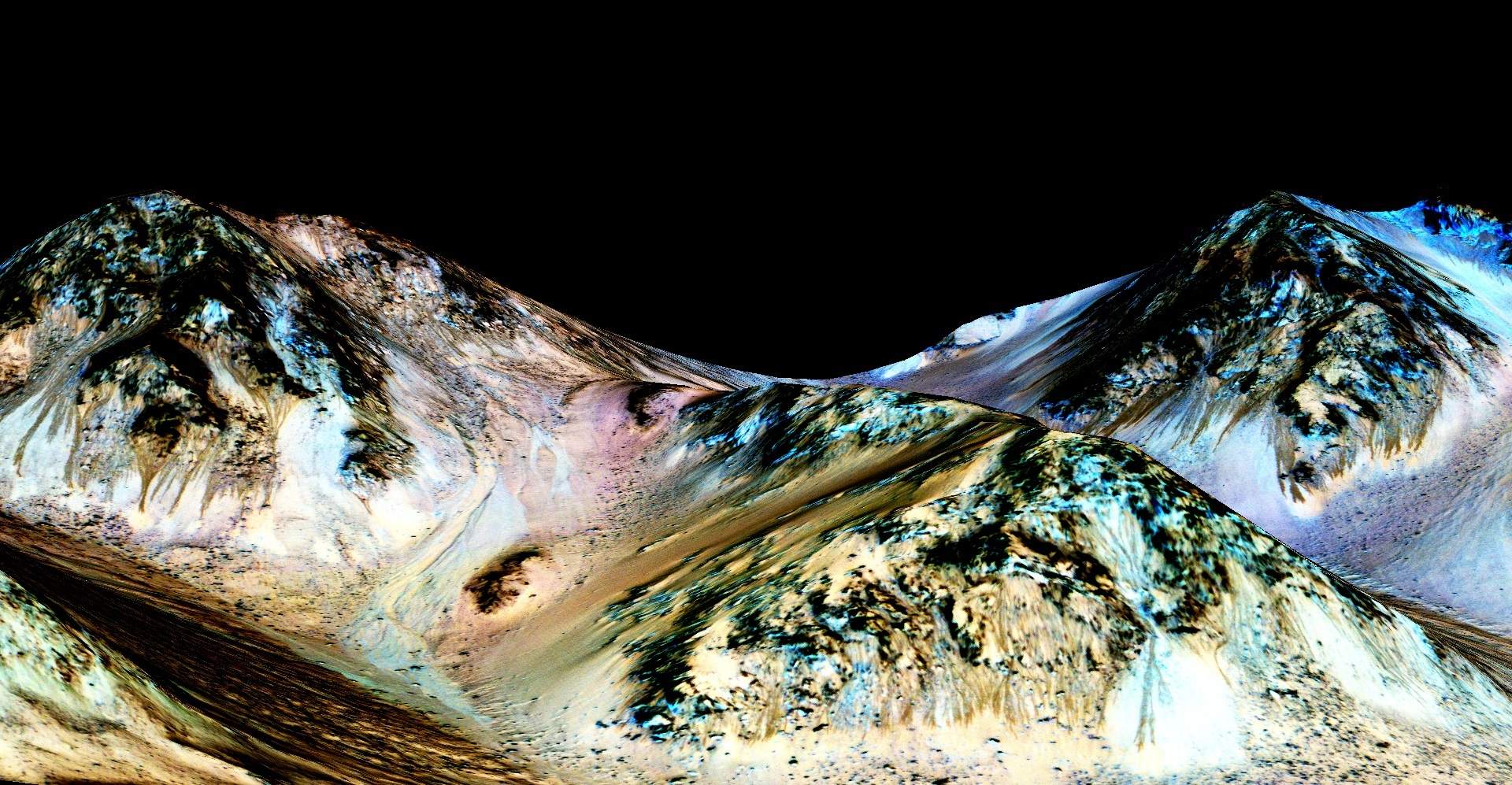

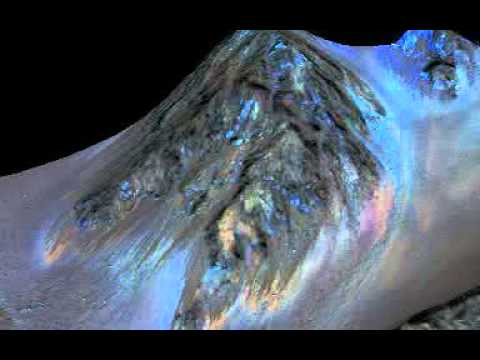

Dark, narrow streaks stretch their fingers down Mars’ slopes every warm season. Those dark veins disappear when the weather cools down. For a long time, scientists have thought these streaks come from a salty brine that’s solid in the winter but melts in the springtime, streaming downhill. But since the streaks are only 5 meters wide at most, our satellites couldn’t get a clear enough look to analyze their composition.

Now researchers have found a way to find out what those streaks are made of, using data from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. The MRO’s spectral imager normally can’t make out details smaller than 18 meters across, but a team of researchers has found a way to extract compositional information from individual pixels of data. The study is published in today’s Nature Geoscience.

The researchers found hydrated salts in the areas of Mars where the stripes (known as “recurring slope linea”) appear during warm weather. Hydrated salts are attached to water molecules, and these ones were possibly left behind by evaporated water. In contrast, in the areas where linea never show up, there was no indication of salt.

The findings strongly suggest that the brine hypothesis is correct—in which case, it would mean there’s liquid water on Mars, at least seasonally. That’s great news for scientists who still think life could be lurking on Mars.

Scientists aren’t sure where the water could be coming from every spring. The salts could be absorbing water from the air and liquifying. Or melting ice or even a Martian aquifer could be behind the liquid water.

The water, if it’s there, is really salty—it has to be, in order to remain a liquid at -10 degrees Fahrenheit. (Salts lower the freezing point of water, which is why we put it on our roads in the wintertime.) Still, there are enough salt-loving microbes right here on Earth for scientists to hold out a slim hope that Mars could still be inhabited by simple, single-celled creatures.

Mars doesn’t have the kind of brine we’d want to make pickles in, unfortunately. The spacecraft detected magnesium perchlorate, magnesium chlorate, and sodium perchlorate, which really don’t make the best food additives. These types of salts are highly oxidizing, which means they like to break down organic material, which would certainly make life difficult.

The potential for life on Mars is still a long shot, but worth looking into, the authors write. And John Grunsfeld from NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, agrees. During a press conference he said “I feel it’s even more imperative that we send astrobiologists and scientists to the Red Planet to explore if there’s life on Mars.”

Liquid water on Mars is not only good for any potential microbial Martians living there, but also for the astronauts that NASA hopes to send to Mars one day. Water on Mars could be retrieved as a water source, or split apart into hydrogen and oxygen, which can be used as rocket fuel.

Update 9/28/2015 at 12pm: This article was updated to include information from a NASA press conference.