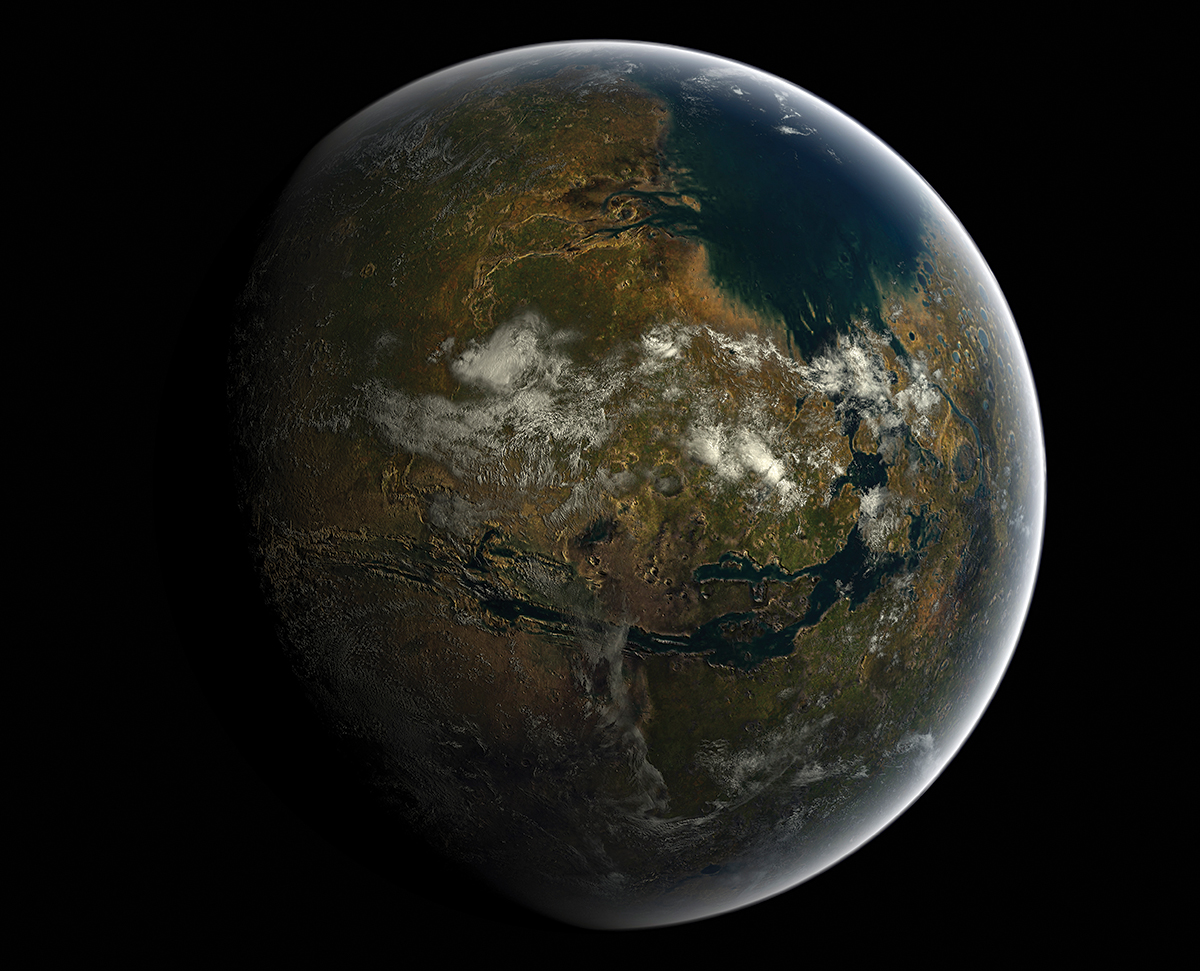

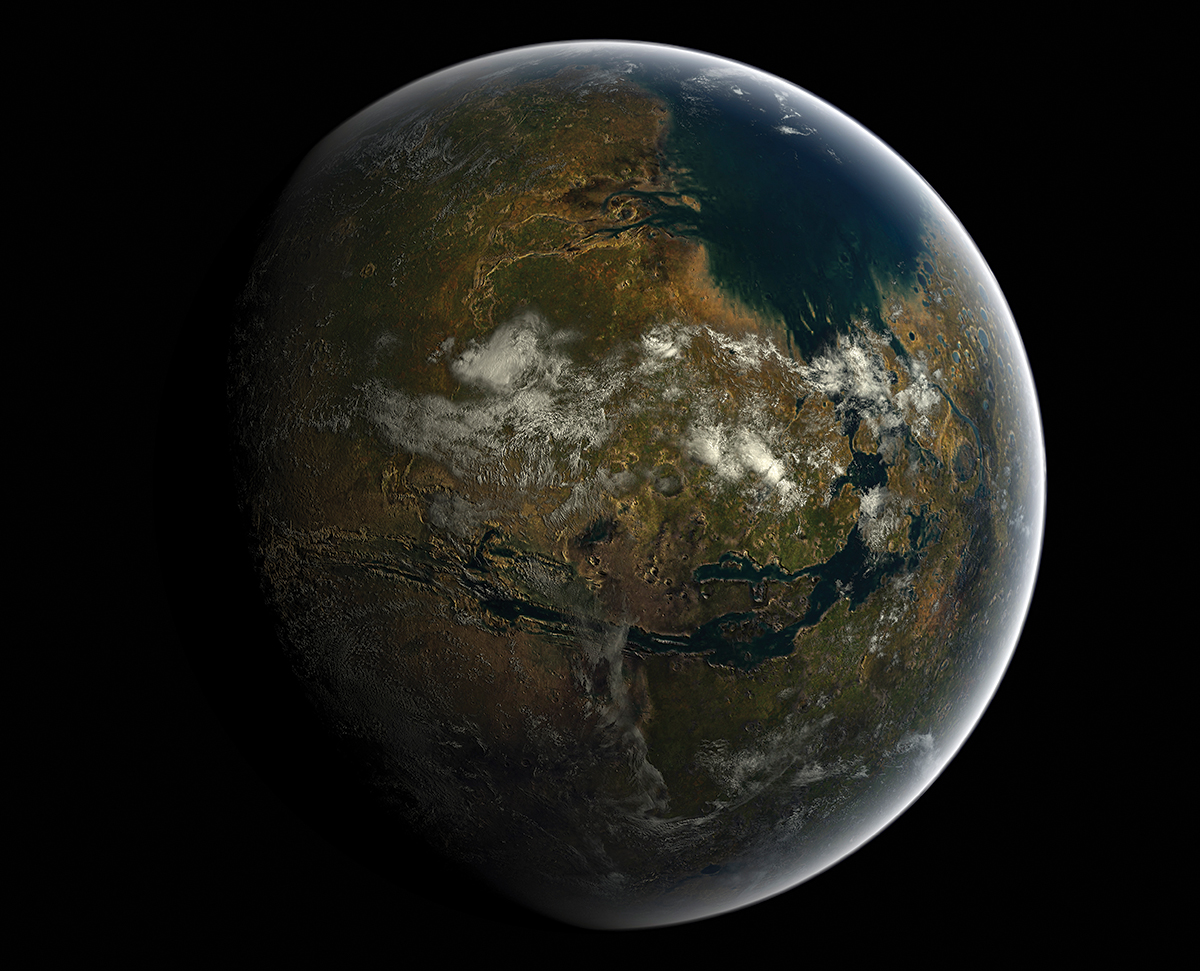

The recipe for creating a habitable planet turns out to be surprisingly simple: Just add water—and atmospheric gases. Mars has both, relics from four billion years ago when the planet was warm and wet. “When it comes to Mars, and only Mars, the notion of terraforming is no longer in the realm of science fiction,” says NASA astrobiologist Chris McKay. Humans could warm the planet and restore a thick atmosphere in a matter of decades, but producing breathable levels of oxygen would take 100,000 years with today’s best technology: plants. New inventions could, in theory, speed that along too. “Living off the land is going to be essential for long-term human explorers beyond Earth,” says Laurie Leshin, a geochemist on the Mars Curiosity team. “We have to figure out how to do this stuff.”

1) Step One: Raise the Temperature

The temperature on Mars hovers around -80°F, but we could raise it by introducing greenhouse gases. “We know how to warm up planets,” McKay says. “That’s what makes terraforming Mars possible.” Martian soil holds the building blocks of perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and we could build factories to extract them using high heat. Pumping PFCs into the Martian atmosphere would kick-start warming, and as the planet’s surface thawed, it would release carbon dioxide frozen into the polar ice caps and soil. That gas would then accelerate warming by trapping reflected solar energy, just as it does on Earth.

2) Step Two: Build the Atmosphere

Today, the Martian atmosphere is only about 1 percent as thick as Earth’s, but scientists believe it was once much thicker. Building it to 30 percent would be enough to keep water in liquid form. In November, the Maven satellite will sample the planet’s upper atmosphere to find out how its gases escaped. If CO2 reacted with elements on Mars’s surface, locking it in soil, that would bode poorly for terraforming. The same fate would likely befall any we release, says Bruce Jakosky, Maven’s lead scientist. But if ultraviolet rays or solar wind destroyed gases or blew them away, building an atmosphere may be possible. Those processes were more powerful in the past, when the sun was younger.

3) Step Three: Release Water

The Red Planet may look parched, but multiple missions confirm it contains plenty of water. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter imaged features near the equator that suggest flowing water during the spring and summer. Orbital radar indicates there may be huge reservoirs of frozen water underground. In fact, the Curiosity rover verified Mars contains about two pints of water in every cubic foot of dirt. “There’s water beneath your feet in most places,” Leshin says, “and it’s convenient because it’s right there at the surface.” Once the deposits melt, the liquid could be collected in reservoirs for drinking and farming. Eventually, a water cycle would support plants and prompt Martian rain.

This article originally appeared in the June 2014 issue of _Popular Science._

Read the rest of _Popular Science’s Water Issue._