This winter, a biotechnology company began offering a whole new service to police departments. Virginia-based Parabon NanoLabs’ Snapshot service allows police to send Parabon NanoLabs DNA samples taken from crime scenes. From that DNA, the company reconstructs a guess of what the person’s face looks like.

“It’s giving investigators new leads,” Ellen McRae Greytak, Parabon’s director of bioinformatics, tells Popular Science. “The idea of Snapshot is to give investigators a new way to use DNA.”

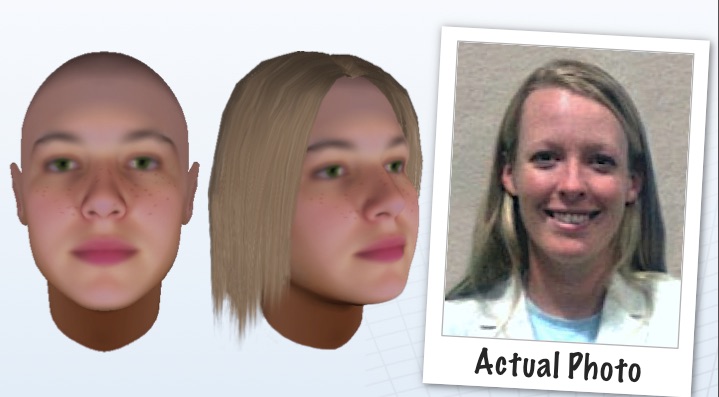

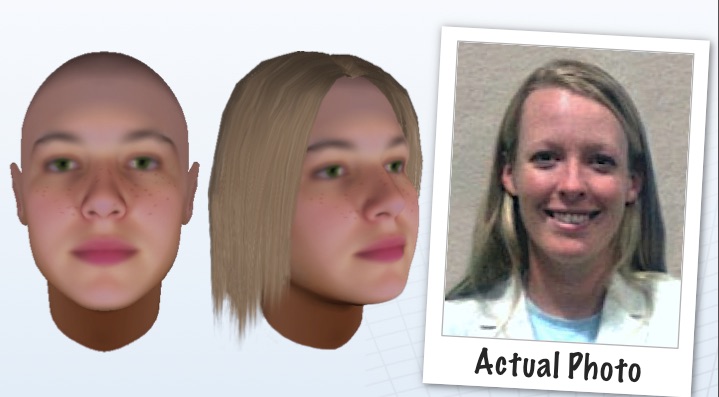

Parabon NanoLabs has worked on 10 cases, each for different U.S. police departments, Greytak says. The first department to release a face prediction publicly is the Columbia, South Carolina, police. The department published this poster made from the DNA of a “person of interest” in the unsolved murder of 25-year-old Candra Alston and her three-year-old daughter in 2011:

In the past few years, researchers have made big strides toward being able to reconstruct people’s appearance from their DNA. Parabon NanoLabs isn’t the first company to think to offering such services to police. Biotech companies Identitas and Illumina both offer eye and hair color guesses from DNA samples. Parabon NanoLabs seems to be unique in offering an illustrated face estimate. Outside experts say the illustrations are not likely to be accurate, however, based on the research that’s been done about the genetics of human faces. Greytak counters that because of proprietary research, Snapshot illustrations are more accurate than one might think—and anyway, they need only to be close enough to jog the memory of a witness. Snapshot hasn’t yet been validated by outside groups, which researchers Popular Science talked to believe should be the next step.

The most controversial aspect of Snapshot is its prediction of the shape of a face. Eye color and hair color have been scientifically shown to be fairly predictable already. However, all the scientific literature that’s publicly available suggests researchers are only starting to get a handle on how to predict a person’s face shape from his genetics. “Based on what the published research shows, I would be very skeptical that at this moment, someone has this knowledge,” says Manfred Kayser, a biologist at the Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands who developed methods for guessing hair and eye color that Illuminas and other companies use.

What makes face shape much more difficult than hair and eye color? It’s controlled by many more genes. Any one gene scientists find that’s associated with face shape has only a small effect. Because hair and eye color are controlled by fewer genes, it’s easier for scientists to find most of them. Even then, they don’t know all. That’s why estimates for eye and hair color from DNA come with numbers such as “90 percent confident.” Meanwhile, the state of the science for predicting skin color from DNA—another aspect of Snapshot’s predictions—is somewhere in between that for eyes and hair and that for face shape.

Greytak agrees Snapshot is not super-precise, nor is the science ready for it to be. “Our goal is not to produce a profile that is perfectly accurate and there is only one person you’ve ever seen who could match that profile,” she says. “Really our goal is to produce something that will look similar enough to a person that it will jog a memory and, at the same time, make it clear which people it is not.”

So how likely is it that police will start reverse-engineering faces for all the DNA they find on a crime scene?

Parabon NanoLabs has done some research that’s a bit different from other face-shape studies. For example, they’ve done big-data-type analyses on 1 million distinctive letters in the human genome, called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs. They searched for single SNPs, as well as combinations of up to five SNPs, that are associated with different face shapes. Many studies seeking SNPs that affect physical traits look at only single SNPs or pairs of SNPs, but it’s thought that most human traits are probably controlled by numerous genes, so Parabon’s methods could have a better shot at meaningful associations than similar, past studies. There’s a big limitation, however. Computers simply can’t test every possible combination; that’s too many calculations. For example, there are 170 quadrillion possible three-SNP combinations in a set of 1 million SNPs. So Parabon uses an algorithm to choose some smaller number of combinations, which it believes are most likely to be important, to test.

It’s unclear whether Parabon NanoLabs’ techniques work better than what’s already published, outside researchers say. The company should submit its data for outside groups to check, says Ranajit Chakraborty, a geneticist at the University of North Texas’ Health Science Center who has researched DNA forensics. Otherwise, the company is selling an opaque tool that police agencies are using. “We need validation of this because this is the only information they would use to bring you or me under attention,” he says.

Greytak says Parabon NanoLabs often validates Snapshot with its clients, who are federal and state law enforcement agencies. The agencies send Parabon NanoLabs DNA samples from people they know. The company generates a face illustration, then the agency sends the company photos of the actual person for comparison. It’s a step many agencies go through before deciding to buy Snapshot for a case, Greytak says. Depending on how voluminous and fresh DNA samples are, a Snapshot illustration may cost up to $5,000 per suspect.

So how likely is it that police will start reverse-engineering faces for all the DNA they find on a crime scene? Will Snapshot become, as Greytak hopes, “a key step in investigations”? The answers might depend on the service’s cost and how much police trust its science, but not on its legality.

Curious whether there might be restrictions on reverse-engineering suspects’ faces, Popular Science contacted David Kaye, a law professor at Pennsylvania State University who specializes in scientific evidence. “Leaving aside the question of whether this can be done accurately, I don’t see any issue, frankly,” he says. Police are generally allowed to figure out as much as they can from a crime scene, he adds.