Influenza B is trying to escape our vaccine

Hell hath no fury like a virus scorned.

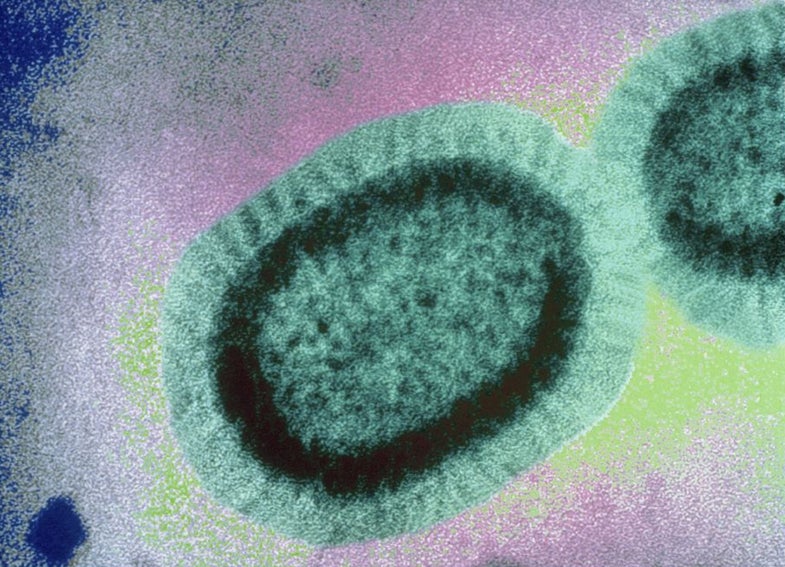

The Flu feels like one big thing. You get your Flu Shot to protect against The Flu during Flu Season. But part of what makes influenza so dangerous is that it’s an astonishingly diverse virus.

Though we’re only aware of it for a few months each year, influenza is constantly circling the world, and as it goes it accumulates new mutations in its genome. Sometimes these mutations don’t change anything substantive, but sometimes they give the virus a survival advantage. And when that happens, the mutation can quickly spread—the older viruses don’t survive as well, so the new, mutated ones take over.

That’s what’s happening in the influenza B virus right now. We spend most of our time worrying about the influenza A strains, which include H1N1 (yes, the swine flu) and H3N2, the latter of which is a particularly nasty subtype that puts more people in the hospital than any other sort of flu. Those A strains get more attention in part because they’re more dangerous, and they’re more dangerous because they mutate faster and are more diverse. That means our annual vaccine selection tends to be wrong for the A strains more often. We only get to pick one strain per subtype—one H1N1 virus and one H3N2 virus—and with so many mutations circulating, it’s hard to pin down exactly which one will cause the most trouble.

The B viruses are less diverse and mutate more slowly, which makes them generally less dangerous. We also get to pick two B strains every year, since the majority of people in the U.S. get a quadrivalent vaccine (meaning it has four parts). Most years there are relatively minor changes to the B virus genome, and therefore small changes to the viruses contained in the vaccine. In the quadrivalent shot, at least, we’ve had the same B strain for the last nine years combined with a rotating set of other, less common B strains.

But this year, the World Health Organization made a change—and the Food and Drug Administration is following the WHO’s lead.

The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee met last Thursday to review the past year’s worth of flu data and decide which influenza viruses will be included in next year’s U.S. vaccine. It’s a tough call, and one they have to make at the beginning of March even though the flu season in question won’t hit Americans until November. One member of the VRBPAC, Pamela McInnes, said on Thursday that “we all take this decision very seriously, and I think we have all been through years of sleepless nights hoping we have done the right thing. This happens to be a difficult year.”

The B strain that made their decision so difficult is known as the Victoria lineage. Flu strains have a complicated nomenclature, but one of the primary ways to differentiate them is by referring to the location where each virus was first isolated. The other main lineage, Yamagata, usually predominates. But the WHO has detected a change in the Victoria lineage that is helping some of its viruses escape our current vaccine.

Jacqueline Katz, the Deputy Director of the CDC’s Influenza Division and Director of the U.S.’s WHO Collaborating Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza, explained last Thursday that they’ve been tracking one mutation in particular for months now. “When I talked to you back in October, I mentioned the emergence of a B Victoria deletion variance,” she said. “Fast forward through to the beginning of this year, and we now see that these viruses have spread to several Central and South American countries. We see them throughout North America, and a number of European countries are now reporting their detection.” That variance is a sequence of two amino acids that have been deleted from the B Victoria genome. It’s a very small change, but the double deletion is different enough from the B viruses in our current vaccines that we’re unprotected from this new variety.

This isn’t entirely unexpected. Influenza mutates constantly in its everlasting quest to stay alive, so it’s inevitable that the B strain would figure out a way to escape the vaccine we’ve been using in some form or another for nine years. That’s why it’s Katz’s job to understand the flu genome. She says in this case, “the [B] virus is clearly looking for something, or somewhere to move too.”

The current B Victoria virus in our flu shot, confusingly termed the “B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus,” doesn’t give much of any protection from the double deletion strain. So researchers went back to the drawing board—a massive database of viruses isolated over the years as the flu virus has evolved. The WHO keeps these candidate strains so that each year they can see which are most similar to the currently circulating virus. That’s how they pick which viruses go into the vaccine: they basically make vaccines from all of the candidate viruses and see which ones protect against the most recently circulating strains.

And despite the double deletion, we do have a candidate virus that protects against this new B subtype: the B/Colorado/06/2017-like virus.

That’s the new virus the WHO is recommending we use in the 2018-19 flu vaccine, and it’s the virus that we’ll use in the U.S. Officials at the FDA think it’s a smart move, especially given that we’ve had many years of the old Brisbane virus—most of the population should be inoculated with that subtype already. Incorporating a new virus into the vaccine means that American immune systems get to see a new type of B virus.

The FDA is also banking on the double deletion virus continuing to grow over the course of this year and becoming the predominant B strain by November. If it does, we should have good protection against it courtesy of this new Colorado strain.

But the problem with the flu vaccine is we don’t know it will grow. Right now the double deletion is spreading, but there’s also a triple deletion subtype the WHO is monitoring. For all we know that strain could become dominant by next year. Or the double deletion type could hit its peak and have virtually disappeared by the time the flu hits the U.S. in November. It’s all very educated guesswork. As Pam McInnes said as last week’s FDA meeting came to a close, “After having served on this committee for many years, this is one of the most difficult meetings we ever go to. The data get stronger and stronger, but somehow the decision doesn’t really get any easier. We’re still sitting with a crystal ball.”