Deep in the Amazonian rainforest, the remote villages of the Yanomami represent some of the final holdouts against Western culture. Though the villagers spot helicopters flying overhead every now and then, some groups have never had contact with Westerners or our modern comforts. By studying one such group, a new paper reveals just how much those modern comforts may be changing the make-up of our bodies.

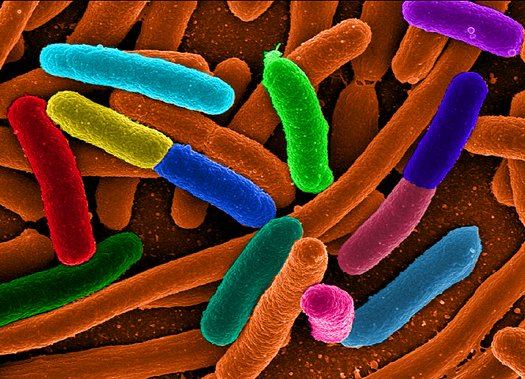

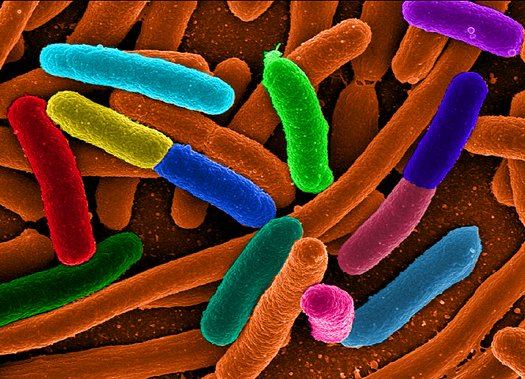

The ecosystem of bacteria that thrives on pretty much every surface of your body plays a big role in your health. Your microbiome can influence your immune system, weight, and even your behavior. And, of course, when the microbial ecosystem gets out of whack, it can make you sick.

A new study in Science Advances studied the microbiomes of a tribe of Yanomami who had never interacted with Westerners before. The scientists swabbed the mouths, skin, and feces of 34 individuals, and sequenced the DNA of the bacteria living there. What they found was that this group of Yanomami had the highest levels of microbial diversity ever reported in a human group.

Because the villagers spend so much time outdoors hunting and gathering, and because they’ve had almost no contact with the antibiotics and processed foods that come along with a Western lifestyle, the researchers suggest that the Yanomami microbiome could give us insight into the microbiomes of our ancestors. The Yanomami carried a higher bacterial diversity than the Guahibo Amerindians in Venezuela and rural Malawian communities in southeast Africa, both of which are more Westernized than the Yanomami. And the Guahibo and Malawians had higher microbial diversity than people in the U.S. The results suggest that the more Westernized a group becomes, the more microbial diversity it loses. That could help to explain a lot of diseases that we get that more traditional cultures do not.

“We believe there is something environmental occurring in the past 30 years that is driving these diseases. We think the microbiome could be involved.”

In a press release, study co-author Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello, who studies the human microbiome at NYU, says the work suggests there may be a link between bacterial diversity, industrialized life, and diseases such as obesity, asthma, allergies, and diabetes. “We believe there is something environmental occurring in the past 30 years that is driving these diseases. We think the microbiome could be involved.”

But before you rush out to stock up on probiotics, William Hanage, a Harvard epidemiologist who wasn’t involved in the new study, told Popular Science that there are a few important things to keep in mind about this study. For one, without a time machine, we’ll never know whether or not the Yanomami microbiome represents the ‘ancestral’ human microbiome, he says.

Secondly, the relationship between the microbiome and human health is really complicated. Though we know that low bacterial diversity is associated with some modern illnesses, it’s not clear whether the low diversity causes the illness or vice versa. “It is a leap to say that more diverse is necessarily healthier,” says Hanage. Plus, some of the microbes carried by the Yanomami could be pathogenic.

Others may have beneficial effects, though. For example, the scientists found that Oxalobacter formigenes, a bacteria that protects against the formation of kidney stones, was present at higher levels in the Yanomami compared to Americans.

The authors hope that studying the microbiomes of groups such as the Yanomami will lead to the discovery of other microbes with therapeutic value. Resupplying those microbes could hold the key to treating the chronic diseases that affect Western populations.

The study had a second important finding: Although the Yanomami microbes were susceptible to antibiotics, the bacteria carried antibiotic resistance genes that, if activated, could make them impervious to even the toughest manmade antibiotics. Since this group of Yanomami had never been exposed to Western culture, this means bacteria don’t need to be exposed to antibiotics to possess antibiotic resistance genes. That’s not altogether surprising, but it’s good to know, especially as disease-causing bacteria in the Western world become increasingly resistant to antibiotics. Says study co-author Gautam Dantas: “A critical part of trying to curb this spread of resistance is of course understanding where it comes from.”