If you regularly read science news, you might think that scientists are obsessed with stem cells. Many of them are, and for good reason: They have an incredible ability to develop into almost any type of cell found in the body. Now that technologies exist to more reliably tweak the human genome, the idea of growing healthy tissues and organs as-needed is sounding less and less like science fiction. In a paper out today in the journal Nature, researchers replaced almost all of a seven-year-old boy’s outer skin layer to treat his life threatening skin condition, a genetic disease called epidermolysis bullosa.

The researchers grew the replacement skin from the boy’s healthy epidermal cells, tweaking their genetic makeup in the lab to ensure the disease-causing mutation wasn’t present. They then attached the new skin to the affected areas of the child’s body. The same group of scientists previously performed a similar procedure on two children with the same condition, but this is the first time they did so on someone with such a severe case. Instead of treating small patches, they replaced 80 percent of his skin surface.

Epidermolysis bullosa prevents the outermost layer of the skin, called the epidermis, from anchoring to the underlying skin layer (the dermis) correctly. As a result, the epidermis falls away when inflicted with even minor trauma, easily causing blisters, ulcers, and in many cases (including the boy in the study) life-threatening wounds on much of the skin surface. Before undergoing the experimental treatment, the young patient described in the study had lost much of his skin to the disease and was admitted to the hospital.

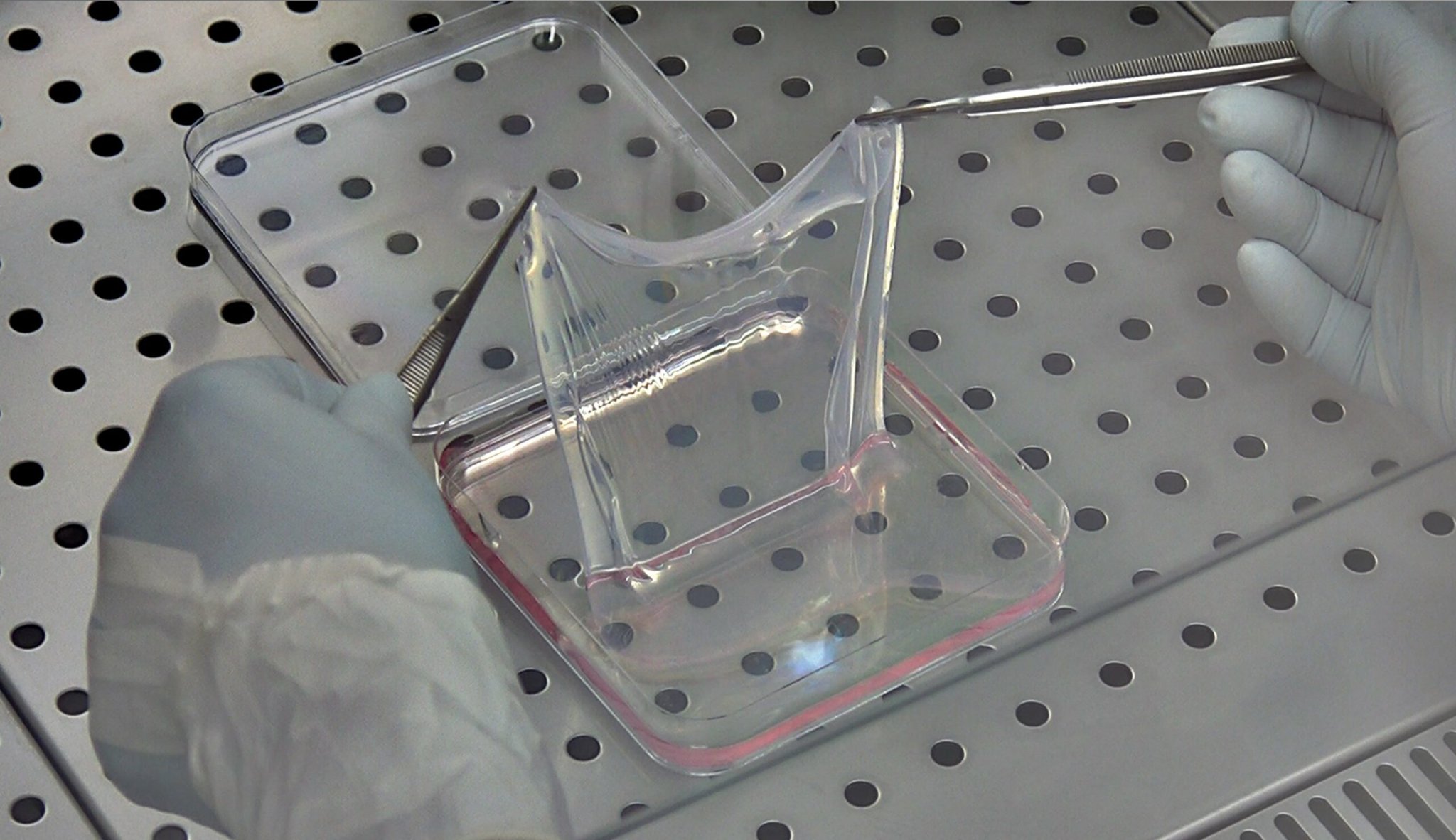

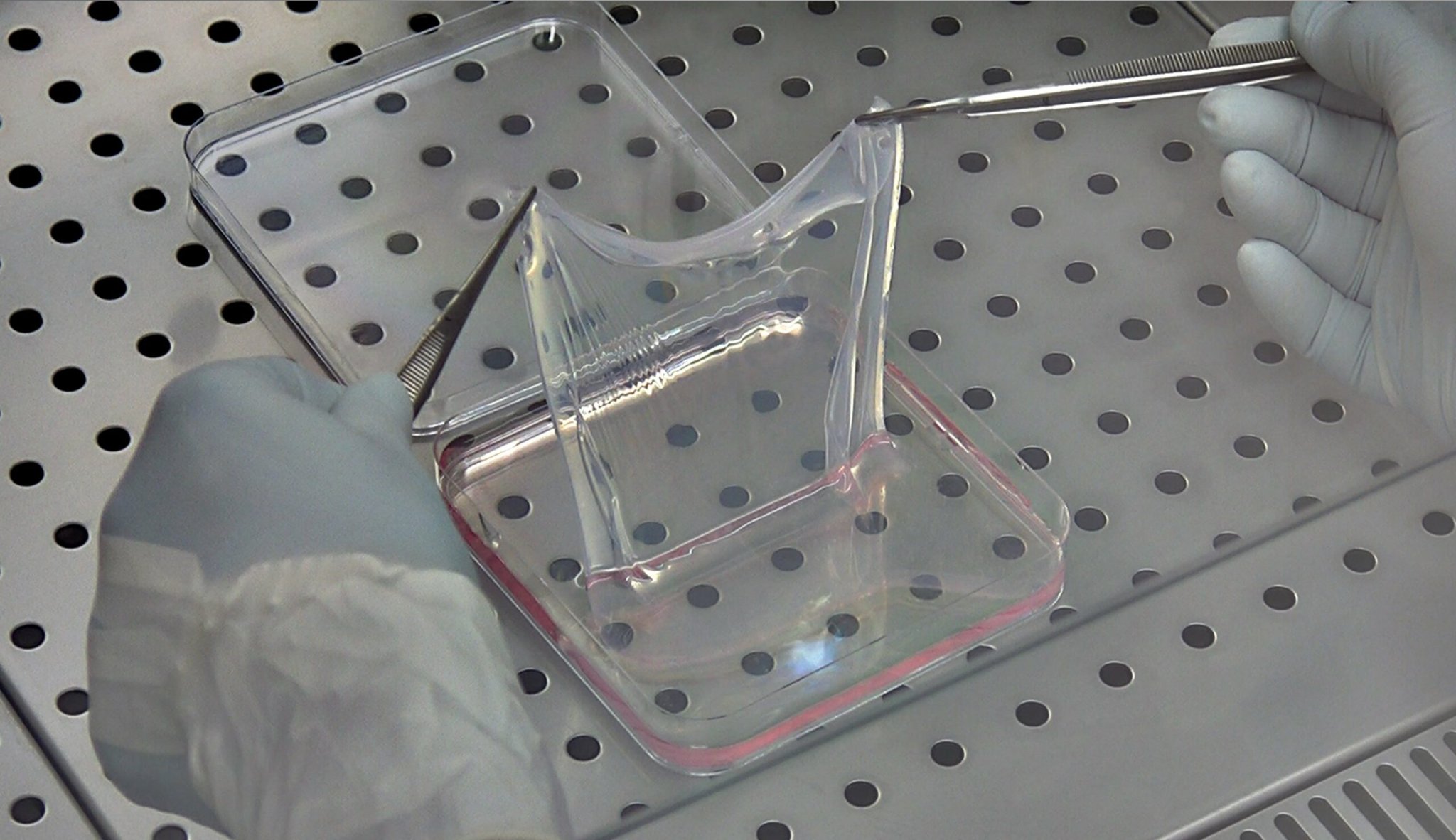

Fortunately, the researchers saw the disease as a prime candidate for their stem cell tweaking technique. They first took a small piece of healthy tissue from an unaffected patch of the boy’s skin. Then, they isolated epidermal cells from that tissue, and using a retroviral vector—essentially a method that viruses use to insert information into a cell—they placed instructions for healthy, non-mutated skin cells into the boy’s own. These cells grew and flourished in the lab, creating the makings of healthy skin. During three surgeries conducted over the course of several months, doctors placed this lab-grown tissue on top of the patient’s dermis so it could continue to grow there.

Eventually, the new skin cells did what all healthy cells do: they replicated. When they did, one particular type of epidermal stem cell—the holoclones—took over and kept growing, developing into new, healthy skin.

The young boy is now out of the hospital, with skin that can handle everyday wear and tear without putting him in peril.

“When he got his new epidermis, his clinical situation improved dramatically,” says study author Michele De Luca, a regenerative medicine researcher at University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy.

The case is a promising step towards the use of lab-grown tissues, but there are definitely limitations. This skin disease was perfect for the procedure in that the outer layer was diseased, but the underlying dermis was still completely intact. So, only the epidermis needed regrowing and subsequent reattaching. This isn’t the case for other skin conditions, the researchers say. Severely burned skin, for example, is often damaged at both layers. Rebuilding the dermis would pose a much tougher challenge.

Nevertheless, this study shows that this method of treatment—replacing part of an organ with genetically corrected stem cells grown in a lab—is feasible. Researchers are currently working on a phase one clinical trial to try it on other people with this specific condition, but future research will help determine if it can help patients with other life-threatening skin problems. If successful, De Luca said in a press conference, it could prove to be a better option than transplants from donors, which carry the risk that the new host’s body will violently reject the foreign cells. Many organ recipients spend the rest of their lives on drugs that suppress the immune system—a dangerous price to pay for a new body part, no matter how badly it’s needed. Edited stem cells offer the tantalizing alternative of an organ that is made from the patient’s own body, but with dangerous imperfections removed. Here’s to hoping that the treatment is ready for prime time soon.