We thought we knew what it looked like, the planet with the broad, striped belt. We scribbled it onto construction paper with crayons and magic markers; built models of it out of styrofoam balls and cheap paint in primary colors. It was our favorite, instantly distinct and distinguished from all the other plain, unadorned worlds.

Then a series of fleeting glances through lenses in space and on the ground convinced us that there was something to our favoritism, so we decided to take a closer look.

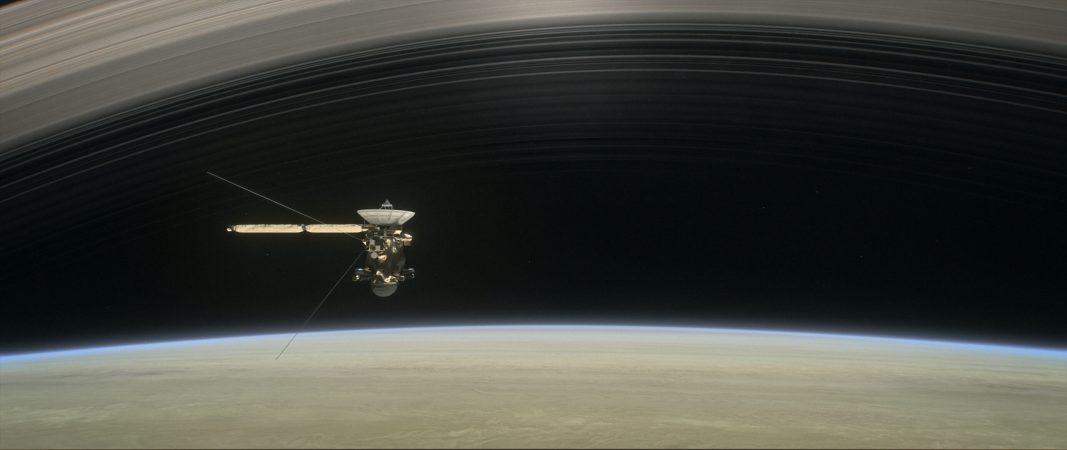

Our eyes had to stay with our bodies and brains, here on Earth, but we could construct something that would extend our gaze, and bring Saturn’s mysteries into a sharper focus. We built a bus-sized, space-faring set of lenses and instruments and recorders, all to give us a chance to illuminate a darkened corner of our stellar neighborhood, over 746 million miles away.

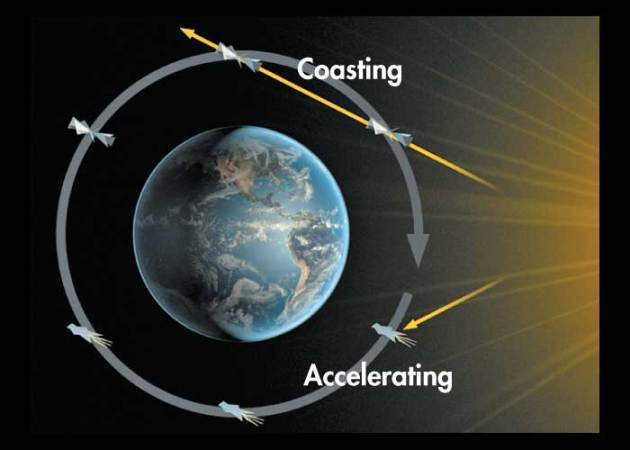

With high hopes, we gave it the name of an Italian-French astronomer, the one who realized in 1675 that Saturn’s rings were not solid rock, but a scattering of tiny moons, moonlets, and cosmic dust strewn about the planet’s middle. We sent it off with paeans and protests and waited for seven years, watching the outer solar system with a vision that we didn’t yet know was blurred.

When our representative at long last reached the end of its pilgrimage and settled into its litany of orbits, it was as though we had finally put on a pair of glasses for the first time, and could at last see individual leaves within a distant arboreal scene—not a verdant and impressionist green blob. Our crayon scribbles of Saturn were no longer adequate, and we drank it all in, keeping our eyes wide open for as long as possible, drawing out the experience for 13 long, full, years.

But the prescription that fit us then no longer meets our needs.

We’ve now tossed those glasses up against the very thing we used to admire through their many-instrumented lenses, smashing them to dust to preserve a future view.

Someday, we will build another set of spectacles, and bring that far-flung world close once more. How could we not, having witnessed the wonders of this system with its planet-esque plethora of moons dancing at a distance or disturbing its edges?

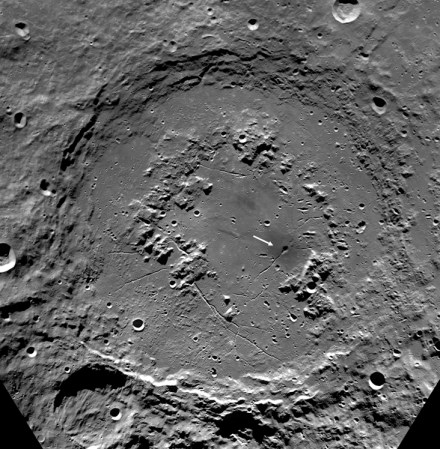

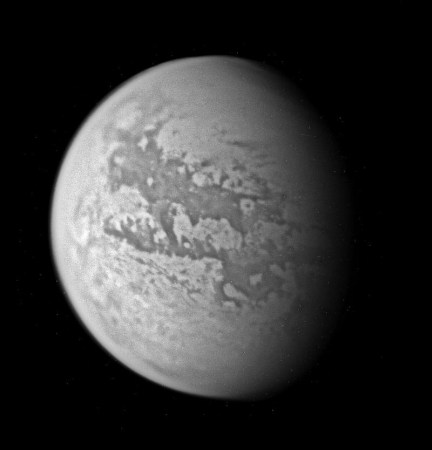

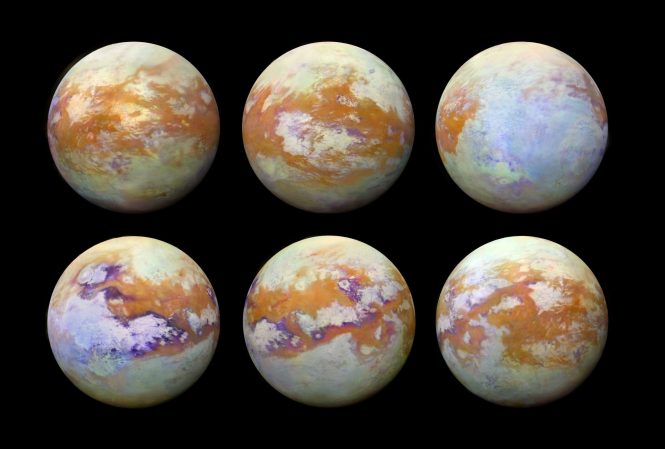

Though we can no longer gaze ravenously at the dumpling-shaped Pan, thirst after Enceladus’ plume, or lose ourselves in Titan’s methane lakes, they will continue to perturb our thoughts, curiousity moonlets leaving a wake of innovation in our minds.

We will eventually scrape the money together to let us see this corner of our solar system clearly again, even if it takes years of effort and pooling the resources of the broader human family. Those new lenses will give us whole new moment of clarity, one that is currently as impossible to comprehend as those first intriguing moments of wonder—when we realized with a jolt that what had seemed so obvious and settled was in fact unnervingly mysterious and vibrant.

Our past selves never would have believed that the best candidates for life lay in underground oceans or pools of hydrocarbon on icy moons, in parts of the solar system far removed from our Sun’s radiance. We never would have guessed that the voids between the rings could be so silent, or that the outermost atmosphere would be full of charged rain.

Compared to the vast knowledge available in the solar system, we have impossibly short lives. Scientists who had young children when they began crafting Cassini are now grandparents, and children who watched Cassini blast off now have PhDs. But together, an intergenerational effort can expand our conception of the universe, and grant us the imagination to dream of what might yet be out there. We may have said farewell this morning, but this need not be our long goodbye.

Saturn: be well, until we meet again. It might take some time, but we will return to you once more.