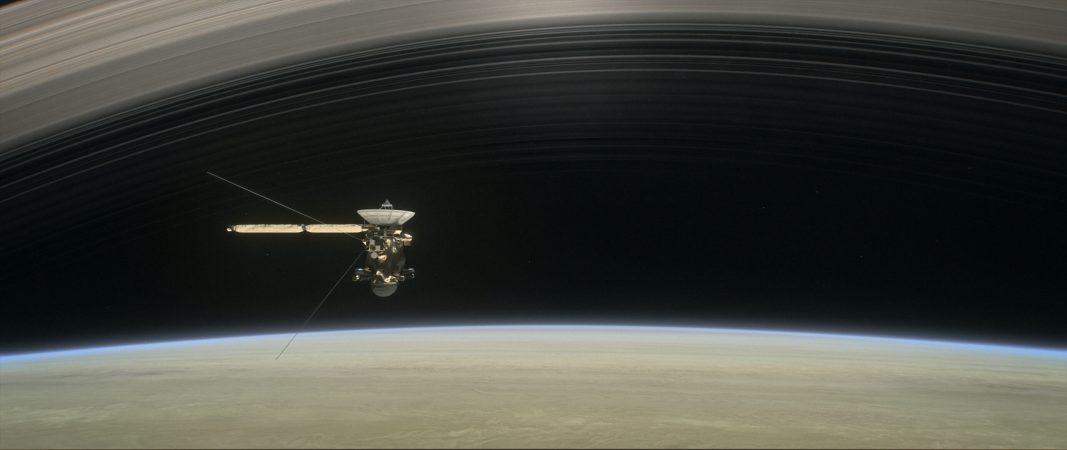

On Tuesday, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft dove between Saturn—the planet it’s spent years studying—and the gas giant’s rings. This was the second of 22 such maneuvers, the last of which will send Cassini careening into Saturn’s atmosphere to meet a fiery end on September 15.

But even with 20 dives left, scientists are already starting to receive surprising data from these unprecedented passes.

When Cassini made its first ring dive on April 26, NASA engineers actually maneuvered the spacecraft’s antenna dish to serve as a protective shield; they worried that particles of dust, debris from the bits of rock that make up Saturn’s rings, might damage Cassini’s electronics. They didn’t expect any particles larger than smoke, but at speeds of 77,000 mph, the spacecraft could have been ruined by a poorly timed collision with even these itty bitty fragments of dust.

But apparently these precautions were unnecessary: the region seems to be relatively free of dust.

“The region between the rings and Saturn is ‘the big empty,’ apparently,” Cassini Project Manager Earl Maize said in a statement. This is good news for the team’s engineers—had Cassini’s first pass shown a minefield of dust fragments, they would have had to continue using its antenna as a shield. But that positioning would have prevented them from using certain instruments at certain times. Now they know they can forge ahead with an unprotected spacecraft (except in the case of four dives that will bring the orbiter through the dustier zone of the inner D ring).

“Cassini will stay the course, while the scientists work on the mystery of why the dust level is much lower than expected,” Maize said.

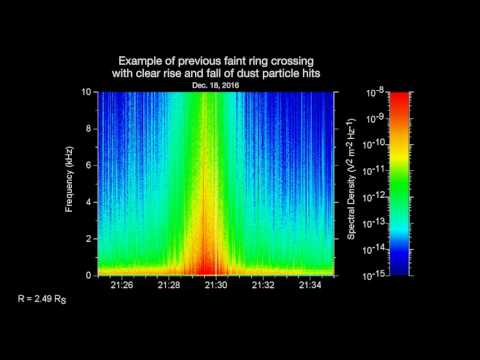

But just how empty is the big empty? Luckily, we have an audio aid. When Cassini’s Radio and Plasma Wave Science (RPWS) antennas collide with dust particles, the (very) tiny explosions that result create electrical signals that researchers can convert into handy-dandy audio and visual formats. RPWS extends beyond the protective coverage of Cassini’s dish-turned-shield, so it provided researchers with portrait of the area’s particle density even as the rest of the spacecraft avoided collisions.

First, listen to the snap, crackle, and pop of dust Cassini collided with during a December 18 ring plane crossing:

You can hear that Cassini collided with more particles—and ‘heard’ more pops—as it crossed the Janus-Epimetheus ring, visualized by the red spike in the video. Now listen to the RPWS data from the first Grand Finale ring dive:

“It was a bit disorienting—we weren’t hearing what we expected to hear,” William Kurth, RPWS team lead at the University of Iowa, said in a statement. “I’ve listened to our data from the first dive several times and I can probably count on my hands the number of dust particle impacts I hear.”

The surprising—and convenient—finding is just a taste of the fantastic science Cassini is sure to do during its final months. The spacecraft has been one of NASA’s greatest successes: its primary mission of surveying the Saturn system was only slotted to last four years, but two extensions have kept it going for nearly a decade more. Its final sacrifice will give researchers an unprecedented look at Saturn’s rings and atmosphere, allowing them to learn new things about the planet’s origin and composition.

The spacecraft should regain contact with Earth later this morning, sending home data from its second ring dive. The third ring crossing will take place on May 9.