This article was originally featured on Hakai.

In August 2014, the Arctic Ocean near the North Pole was suddenly awash with microscopic life—gripped by an algae bloom that covered the Laptev Sea, a large chunk of the East Siberian Sea, and part of the open Arctic Ocean. In a regular year, late summer is a quiet time for the Arctic. Long past is the regular spring phytoplankton bloom that supports so much activity. By August, the algae that bloomed in the spring have sucked most of the nitrogen out of the water, leaving the region practically devoid of microscopic creatures and the larger animals that eat them. So where did this bloom come from?

Because the Arctic Ocean ecosystem is typically limited by the availability of nitrogen, researchers including Douglas Hamilton, an atmospheric scientist at North Carolina State University, started looking for where a glut of the nutrient might have come from to trigger the bloom. One by one, Hamilton and his colleagues examined various ocean-based sources, such as the upwelling of cold nutrient-rich water or the runoff from rivers. Nothing seemed to add up.

Convinced that no oceanic source was bringing in enough excess nitrogen to spark such a massive bloom, the scientists were left with just one option. “The only place left was the atmosphere,” Hamilton says.

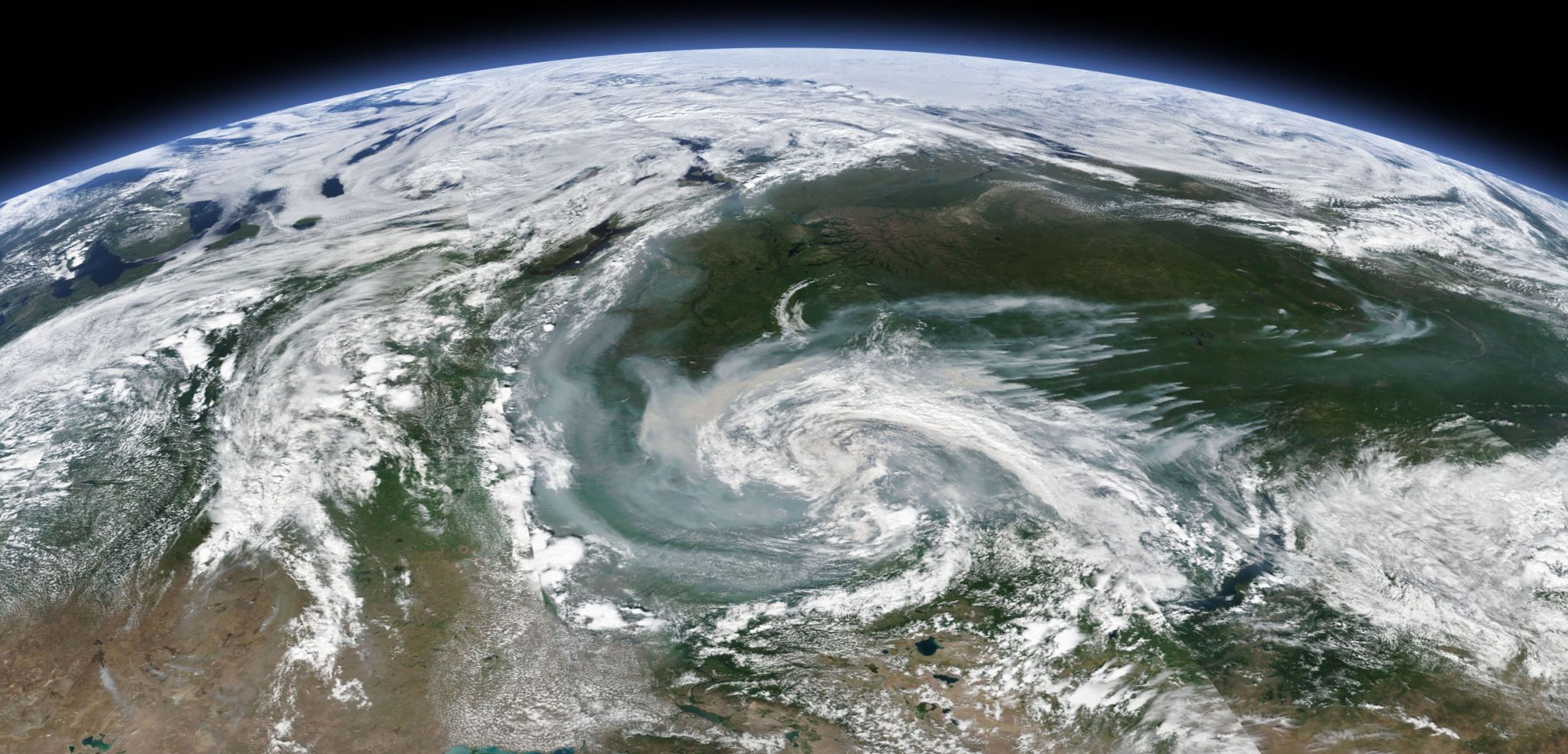

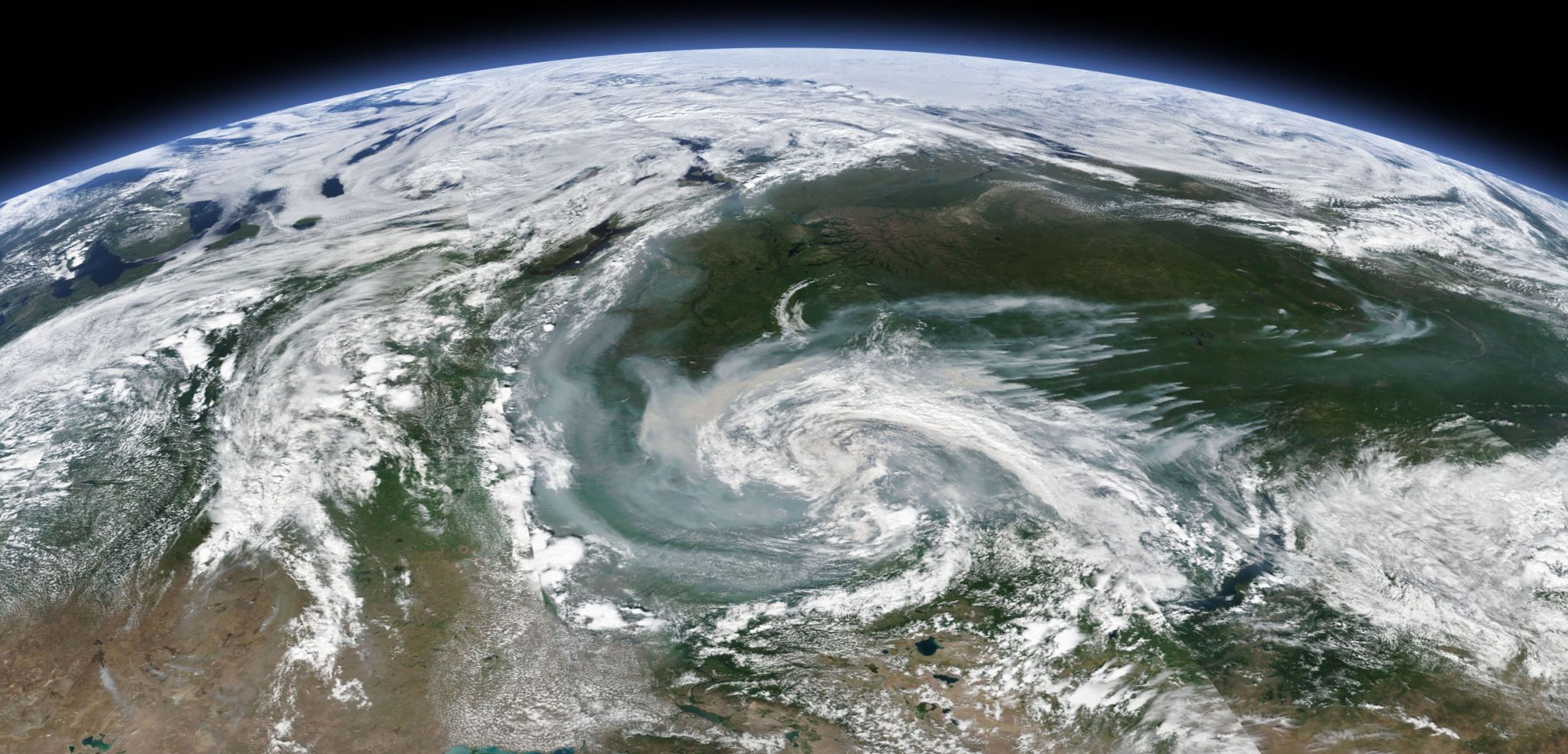

Eventually, the scientists pinned down the most likely culprit: huge wildfires that were raging across Siberia thousands of kilometers south—fires that were burning through forests and, notably, nitrogen-rich peat. The smoke from those fires had drifted north where it deposited its nitrogen in the nutrient-starved water.

The work echoes a similar study, published last year, which shows that iron in the aerosols from wildfires in Australia in late 2019 and early 2020 fertilized anomalous algae blooms in the Southern Ocean. Joan Llort, a biogeochemical oceanographer at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center in Spain who worked on that study, says that as wildfires increase in frequency and intensity because of climate change, especially at higher latitudes, we may see more of these fertilization events and increasing numbers of blooms in traditionally nutrient-poor regions.

“We can’t say for certain yet as we have only recorded a couple of these events so far, but it seems to be going in that direction,” Llort says.

For many coastal areas, more algae blooms could be a problem. Some algae release toxins, while the decomposition of all that phytoplankton can deplete oxygen levels in the water. Increasing wildfires in California, for instance, could bring more harmful blooms to the Pacific coast, says Llort.

In the Arctic, however, the changes could be much more profound.

The Far North is undergoing a process of “borealization.” Rapidly warming and increasingly ice-free, the Arctic Ocean is coming to look a lot more like the North Atlantic. In fact, fish from boreal regions farther south are already shifting north, chasing their preferred water temperature. But the Arctic Ocean is much less productive than the North Atlantic. Even though the temperature is right, these migrating fish are not finding everything they need to survive. For these new arrivals to thrive, the Arctic Ocean will require big new inputs of nutrients to support them. Like the input from wildfires.

For the Arctic Ocean, then, if increasing wildfires and the 2014 bloom are a sign of things to come, this higher flow of nutrients could transform Arctic ecosystems.

“If we keep seeing more of this in the future,” Hamilton says, “we can expect the Arctic Ocean to be getting significantly more nitrogen than it has been for the past several thousand years.”